Roger Joseph Boscovich

[6] Boscovich was born on 18 May 1711 in Dubrovnik, Republic of Ragusa, to Paola Bettera (1674–1777), daughter of a local nobleman of Italian origin, and Nikola Bošković, a Ragusan merchant.

[10] While his father, Nikola, had once been a prolific trader who traveled through the Ottoman Empire, Ruđer only knew him as a bedridden invalid; he died when his son was 10 years old.

Boscovich's mother Paola, nicknamed "Pavica", was a member of a cultivated Italian merchant family established in Dubrovnik in the early 17th century, when her ancestor, Pietro Bettera, settled from Bergamo in northern Italy.

His eldest brother, Božo Bošković (Boško, called Natale by Roger in private correspondence[11]), thirteen years older, joined the service of the Ragusa Republic.

He also wrote verse in both Latin and "Illyrian" (the Renaissance era name for Serbo-Croatian), but eventually burnt some of his manuscripts out of a scrupulous modesty.

Another brother, Ivan (Đivo) Bošković, became a Dominican in a sixteenth-century monastery in Dubrovnik, whose church Ruđer knew as a child with its rich treasures and paintings by Titian and Vasari, still there today.

At the age of 8 or 9, after acquiring the rudiments of reading and writing from Father Nicola Nicchei of the Church of St Nicholas, Ruđer was sent for schooling to the local Jesuit Collegium Ragusinum.

We learn nothing from Bošković himself until the time he entered the novitiate in 1731, but it was the usual practice for novices to spend the first two years not in the Collegium Romanum but in Sant'Andrea delle Fratte.

[8] He was especially appropriate for this post due to his acquaintance with recent advances in science, and his skill in a classical severity of demonstration, acquired by a thorough study of the works of the Greek geometers.

Several years before this appointment he had made a name for himself with a solution of the problem of finding the Sun's equator and determining the period of its rotation by observation of the spots on its surface.

Notwithstanding the arduous duties of his professorship, he found time for investigation in various fields of physical science, and he published a very large number of dissertations, some of them of considerable length.

Among the subjects were the transit of Mercury, the Aurora Borealis, the figure of the Earth, the observation of the fixed stars, the inequalities in terrestrial gravitation, the application of mathematics to the theory of the telescope, the limits of certainty in astronomical observations, the solid of greatest attraction, the cycloid, the logistic curve, the theory of comets, the tides, the law of continuity, the double refraction micrometer, and various problems of spherical trigonometry.

[citation needed] In 1742, he was consulted, with other men of science, by Pope Benedict XIV, as to the best means of securing the stability of the dome of St. Peter's, Rome, in which a crack had been discovered.

An account was published in 1755, under the name De Litteraria expeditione per pontificiam ditionem ad dimetiendos duos meridiani gradus a PP.

A French translation appeared in 1770 which incorporated, as an appendix, some material first published in 1760 outlining an objective procedure for determining suitable values for the parameters of the fitted model from a greater number of observations.

Bošković was selected to undertake an ambassadorship to London in 1760, to convince the British that nothing of the sort had occurred and provide proof of Ragusa's neutrality.

He arrived late and then travelled to Poland via Bulgaria and Moldavia then proceeding to Saint Petersburg where he was elected as a member of Russian Academy of Sciences.

Bošković visited Laibach, the capital of Carniola (now Ljubljana, Slovenia), at least in 1757, 1758, and 1763, and made contact with the Jesuits and the Franciscan friars in the town.

Both Vega and the Rationalist philosopher Franz Samuel Karpe educated their students in Vienna about the ideas of Bošković and in the spirit of his thought.

He was invited by the Royal Society of London to undertake an expedition to California to observe the transit of Venus in 1769 again, but this was prevented by the recent decree of the Spanish government expelling Jesuits from its dominions.

Uncertainty led him to accept an invitation from the King of France to come to Paris where he was appointed director of optics for the navy, with a pension of 8,000 livres and a position was created for him.

[17] In 1783, he returned to Italy and spent two years at Bassano, occupying himself with the publication of his Opera pertinentia ad opticam et astronomiam, etc., published in 1785 in five volumes quarto.

[18] Knowing with complete accuracy both the location and velocity of a particle violates the uncertainty principle of modern quantum mechanics, so it is unclear if this is physically possible.

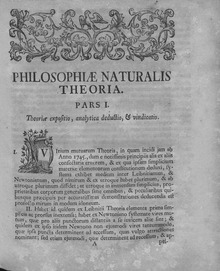

In 1873, Nietzsche wrote a fragment called 'Time Atom Theory', which was a reworking of Boscovich's Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis redacta ad unicam legem virium in natura existentium.

In 1987, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Boscovich death, the Yugoslav state Post based in Belgrade made a postage stamp and postcard on which is written that Boskovich was "the greatest Croatian scientist of his time".

For this reason the attribution of a definite "nationality" to personalities of the previous centuries, living in ethnically mixed regions, is often indeterminable; Bošković's legacy is consequently celebrated in Croatia, Italy and Serbia.