Classical Anatolia

Although our principal source for this period, Herodotus of Halicarnassus, implies this was a swift process, it is more likely that it took four years to subdue the region completely, and the Ionian colonies on the coastal islands remained largely untouched.

[2] Hellespontine Phrygia lay to the north of the Lydia/Sardis satrapy, incorporating Troad, semi-autonomous Mysia, and Bithynia with its capital at Dascylium (modern day Ergili) on the south of the Hellespont.

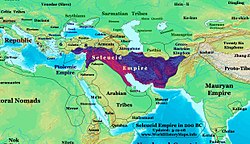

Immediately moving to take commands of the new lands in Europe, Thrace and Macedonia he crossed into Thracian Chersonese when he was assassinated near Lysimachia by Ptolemy Keraunos, future king of Macedon.

In the east provinces were breaking away, while in Asia Minor, subject states were becoming increasingly independent, including Bithynia, Pontus, Pergamum and Cappadocia (traditionally difficult to subjugate).

Pompey had dislodged Mithridates from Pontus by 65 BC, who now retreated to his northern domains but was defeated by rebellion in his own family and died, possibly by suicide, ending the Pontine Kingdom as it then existed.

It was originally just part of the Chalcedon peninsula but was extended to include Nicaea and Prusa and the cities of the coast, east towards Heraclea and Paphlagonia, and south across the Propontis to Mysian Olympus.

Zipoetes was succeeded by his son Nicomedes I (278 – 255 BC) who was instrumental in inviting aid from the Gauls, who having entered Anatolia settled in Galatia were to prove a source of problems in Bithynian affairs.

His son in turn, Ariarathes III (255 – 220 BC) adopted the title of king, and sided with Antiochus Hierax against the Seleucid Empire and expanded his frontiers to include Cataonia.

The period of greatest Armenian expansion occurred with Tigranes II (The Great; 95–55 BC) who made it the most powerful state east of Rome, as the various kingdoms of western Anatolia were absorbed into the Roman sphere of influence.

The aggressive behaviour of both Pontus and Armenia inevitably and fatally brought them into conflict with the eastward Roman expansion with the Armenians suffering a decisive defeat at the Battle of Tigranocerta (69 BC).

The Republic of Rhodes, as an ally of Rome in the war, was granted former Seleucid lands sharing western Anatolia with Pergamon including Caria and Lycia, referred to as the Peræa Rhodiorum.

Direct invasion of Anatolia did not occur until the Seleucid Empire expanded its frontiers into Europe, and was crushed by Rome and its allies in 190 BC, forcing it to retreat to the eastern part of the region.

[12] During the period just after Rome's victory, the Aetolian League desired some of the spoils left in the wake of Philip's defeat, and requested a shared expedition with the Seleucid emperor Antiochus III (223–187 BC) to obtain it.

[12][36] Mithridates' problems were further complicated by a 'rogue' Roman army dispatched by Sulla's enemies in Rome, commanded by Flaccus and then by Gaius Flavius Fimbria which crossed from Macedonia through Thrace to Byzantium and ravaged western Asian Minor before inflicting a defeat on the Pontic forces on the Rhyndacus river.

Lucullus was assembling his legions in northern Phrygia, when Mithridates advanced rapidly through Paphlagonia into Bithynia, where he joined his naval forces and defeated the Roman fleet commanded by Cotta at the Battle of Chalcedon.

Lucullus was formally replaced in 67 BC by Marcius Rex, ordered to deal with the Cilician pirate problem, that was threatening the Roman food supply in the Aegean, and Acilius Glabrio to take over the eastern command.

In 25 BC, Amyntas died while pursuing enemies in the Taurus mountains, and Rome claimed his lands as a new province, leaving western and central Anatolia completely in Roman hands.

Cappadocia continued as an independent client, at one point being united with Pontus, until the Emperor Tiberius deposed the last monarch Archelaus (36 BC – 17 AD), creating a province of the same name.

In the year's following Pompey's departure the Roman administration in Anatolia kept a wary and at times fearful eye on Parthia on its eastern borders, while the central government in Rome was focussed on Julius Caesar and the events in Western Europe.

In 53 BC Marcus Licinius Crassus led an expedition from Syria into Mesopotamia which proved disastrous, the Parthians inflicting huge losses at the Battle of Carrhae in which he was killed.

Since the roads to central Europe through Macedonia, Italy, and Germania were all defended successfully by the Romans, the Goths found Anatolia to be irresistible due to its wealth and deteriorating defenses.

Order and stability was restored when Diocletian (284–305) obtained power following the death of the last Crisis Emperors, Numerian (282–284), and overcoming his brother Carinus, ushering in the next and final phase of the Roman Empire, the Dominate.

On the eastern front, Persia renewed hostilities in 296, inflicting losses on Galerius' forces, until Diocletian brought in new troops from further west the following year and clashed with the Persians in lesser Armenia, and pursued them all the way to Ctesiphon in 298, effectively ending the campaign.

At the end of the 3rd century, the vast empire was beset by administrative and fiscal problems, and much of the power lay in the hands of the military, while there was no clear principle of succession and dynasties were short lived, their fate often determined by force of arms rather than legitimacy.

[62] Constantine's major contribution to religion in the empire was to summon the elders of the Christian world to the great Council of Nicaea in 325 to resolve differences and establish orthodoxy, such as the date of Easter.

Roads were built to connect the larger cities in order to improve trade and transportation, and the abundance of high outputs in agricultural pursuits made more money for everyone involved.

For a brief time the empire was reunited (378–379) under the western emperor Gratian (375–383), son of Valentinian I and nephew of Valens, before he realised he needed someone to rule in the east separately, dispatching his brother in law, Theodosius I (379–395), to Constantinople.

In the North lay Armenia maior had provincial status, while the southern part consisted of a federation of six satrapies or principalities (Ingilene, Sophene, Anzitene, Asthianene, Sophanene and Balabitene) allied to the empire.

Put together these various Pauline sources suggest considerable missionary activity by Paul and Barnabas throughout Anatolia, and adherence to the new faith in both Jewish and hellenised Gentile society.

[74] Another New Testament source, the Revelation refers to the Seven Churches of Asia (Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamon, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea), a list which includes not only large urban centres but also smaller towns.