Religion in ancient Rome

Religion depended on knowledge and the correct practice of prayer, rite, and sacrifice, not on faith or dogma, although Latin literature preserves learned speculation on the nature of the divine and its relation to human affairs.

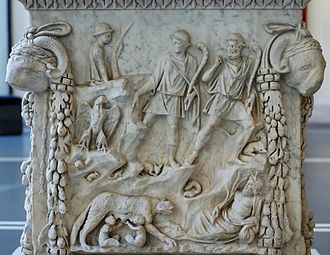

The Roman triumph was at its core a religious procession in which the victorious general displayed his piety and his willingness to serve the public good by dedicating a portion of his spoils to the gods, especially Jupiter, who embodied just rule.

[citation needed] As the Romans extended their dominance throughout the Mediterranean world, their policy in general was to absorb the deities and cults of other peoples rather than try to eradicate them,[3] since they believed that preserving tradition promoted social stability.

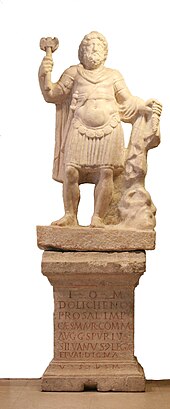

[5] By the height of the Empire, numerous international deities were cultivated at Rome and had been carried to even the most remote provinces, among them Cybele, Isis, Epona, and gods of solar monism such as Mithras and Sol Invictus, found as far north as Roman Britain.

[7] According to mythology, Rome had a semi-divine ancestor in the Trojan refugee Aeneas, son of Venus, who was said to have established the basis of Roman religion when he brought the Palladium, Lares and Penates from Troy to Italy.

Romulus and Remus regained their grandfather's throne and set out to build a new city, consulting with the gods through augury, a characteristic religious institution of Rome that is portrayed as existing from earliest times.

The first "outsider" Etruscan king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, founded a Capitoline temple to the triad Jupiter, Juno and Minerva which served as the model for the highest official cult throughout the Roman world.

[16] Rome offers no native creation myth, and little mythography to explain the character of its deities, their mutual relationships or their interactions with the human world, but Roman theology acknowledged that di immortales (immortal gods) ruled all realms of the heavens and earth.

[21] In this spirit, a provincial Roman citizen who made the long journey from Bordeaux to Italy to consult the Sibyl at Tibur did not neglect his devotion to his own goddess from home: I wander, never ceasing to pass through the whole world, but I am first and foremost a faithful worshiper of Onuava.

[27] The meaning and origin of many archaic festivals baffled even Rome's intellectual elite, but the more obscure they were, the greater the opportunity for reinvention and reinterpretation – a fact lost neither on Augustus in his program of religious reform, which often cloaked autocratic innovation, nor on his only rival as mythmaker of the era, Ovid.

Lares might be offered spelt wheat and grain-garlands, grapes and first fruits in due season, honey cakes and honeycombs, wine and incense,[40] food that fell to the floor during any family meal,[41] or at their Compitalia festival, honey-cakes and a pig on behalf of the community.

[75] For those who had reached their goal in the Cursus honorum, permanent priesthood was best sought or granted after a lifetime's service in military or political life, or preferably both: it was a particularly honourable and active form of retirement which fulfilled an essential public duty.

The Arvals offered prayer and sacrifice to Roman state gods at various temples for the continued welfare of the Imperial family on their birthdays, accession anniversaries and to mark extraordinary events such as the quashing of conspiracy or revolt.

A tale of miraculous birth also attended on Servius Tullius, sixth king of Rome, son of a virgin slave-girl impregnated by a disembodied phallus arising mysteriously on the royal hearth; the story was connected to the fascinus that was among the cult objects under the guardianship of the Vestals.

Most Roman authors describe haruspicy as an ancient, ethnically Etruscan "outsider" religious profession, separate from Rome's internal and largely unpaid priestly hierarchy, essential but never quite respectable.

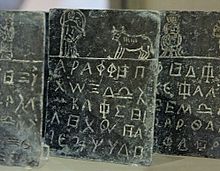

[104] Mystery cults operated through a hierarchy consisting of transference of knowledge, virtues and powers to those initiated through secret rites of passage, which might employ dance, music, intoxicants and theatrical effects to provoke an overwhelming sense of religious awe, revelation and eventual catharsis.

Ancient votive deposits to the noble dead of Latium and Rome suggest elaborate and costly funeral offerings and banquets in the company of the deceased, an expectation of afterlife and their association with the gods.

[109] As Roman society developed, its Republican nobility tended to invest less in spectacular funerals and extravagant housing for their dead, and more on monumental endowments to the community, such as the donation of a temple or public building whose donor was commemorated by his statue and inscribed name.

Juno, Diana, Lucina, and specialized divine attendants presided over the life-threatening act of giving birth and the perils of caring for a baby at a time when the infant mortality rate was as high as 40 percent.

[138] Lucan depicts Sextus Pompeius, the doomed son of Pompey the Great, as convinced "the gods of heaven knew too little" and awaiting the Battle of Pharsalus by consulting with the Thessalian witch Erichtho, who practices necromancy and inhabits deserted graves, feeding on rotting corpses.

[8] In the late Republic, the so-called Marian reforms supposedly did the following: lowered an existing property bar on conscription, increased the efficiency of Rome's armies, and made them available as instruments of political ambition and factional conflict.

Sissel Undheim has argued that, with their Religions of Rome volumes, Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price dismantled the well-established narrative of the decline of religious in the late Republic, opening the way for more innovative and dynamic perspectives.

[171] Major cult centres to "non-Roman" deities continued to prosper: notable examples include the magnificent Alexandrian Serapium, the temple of Aesculapeus at Pergamum and Apollo's sacred wood at Antioch.

In the Provinces, this would not have mattered; in Greece, the emperor was "not only endowed with special, super-human abilities, but... he was indeed a visible god" and the little Greek town of Akraiphia could offer official cult to "liberating Zeus Nero for all eternity".

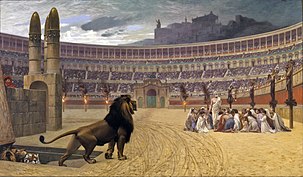

In the wake of religious riots in Egypt, the emperor Decius decreed that all subjects of the Empire must actively seek to benefit the state through witnessed and certified sacrifice to "ancestral gods" or suffer a penalty: only Jews were exempt.

Origen discussed theological issues with traditionalist elites in a common Neoplatonist frame of reference – he had written to Decius' predecessor Philip the Arab in similar vein – and Hippolytus recognised a "pagan" basis in Christian heresies.

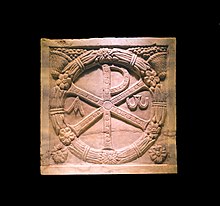

[197] Meanwhile, Aurelian (270–75) appealed for harmony among his soldiers (concordia militum), stabilised the Empire and its borders and successfully established an official, Hellenic form of unitary cult to the Palmyrene Sol Invictus in Rome's Campus Martius.

He not only refused to restore Victory to the senate-house, but extinguished the Sacred fire of the Vestals and vacated their temple: the senatorial protest was expressed in a letter by Quintus Aurelius Symmachus to the Western and Eastern emperors.

The region's mountainous terrain allowed the Maniots to evade the Eastern Roman Empire's Christianization efforts, thus preserving pagan traditions, which coincided with significant years in the life of Gemistos Plethon.

The modern Roman religion, unlike other neopagan movements, is regarded as having been transmitted esoterically through families such as the Latriani, connected to the Medici and inspired by George Gemistus Plethon, who contributed to the founding of the Neoplatonic Academy in Florence.