Succession of the Roman Empire

[17][18] The reference to Germany (Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Germanicæ), which first appeared in the late 15th century, was never much used in official Imperial documents,[19] and even then was a misnomer since the Empire's jurisdiction in Italy had not entirely disappeared.

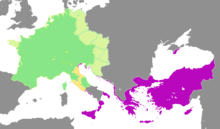

Thus, the Imperial identity, and therefore the question of which polity could rightfully claim to be the Roman Empire, rested not on a single criterion but on a variety of factors: dominant territorial power and the related attributes of peace and order; rule over Rome and/or Constantinople; protection of justice and of the Christian faith (against paganism, heresy, and later Islam); as well as, albeit only intermittently, considerations of dynastic succession or of ethnic nationalism.

Here Louis apparently refers to a claim by Basil that the Emperor should be a Roman and not from a non-Roman ethnicity (gens): It is only right to laugh at what you said about the imperial name being neither hereditary (paternum) nor appropriate for a people (neque genti convenire).

(...) Since things are so, why do you take such effort to criticise us, because we come from the Franks and have charge of the reins of the Roman empire (imperium), since in every people (gens) anyone who fears God is acceptable to Him?

Earlier examples include the preference of several barbarian kingdoms during the Migration Period for Arianism after the competing Nicene Creed had regained dominance in Constantinople: the Burgundians until 516, Vandals until 534, Ostrogoths until 553, Suebi until the 560s, Visigoths until 587, and Lombards intermittently until 652.

[citation needed] On two occasions, the Eastern (Byzantine) Emperors reunited their church with its Western (Roman Catholic) counterpart, on political motivations and without durable effect.

[25] The Fourth Crusade and sack of Constantinople in 1204 marked a major rupture in the history of the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire, and opened a period of fragmentation and competing claims of Imperial legitimacy.

The Empire shrunk considerably during that period, and at the end it was only the imperial city itself without any hinterland, plus most of the Peloponnese (then referred to as Morea) typically under the direct rule of one of the Emperor's sons with the title of Despot.

Charles I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, who also claimed descent from the Palaiologos family, declared in 1612 his intent to reclaim Constantinople but only succeeded in provoking an uprising in the Mani Peninsula, which lasted until 1619.

[29] In 1454, he ceremonially established Gennadius Scholarius, a staunch antagonist of Catholicism and of the Sultan's European enemies, as Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and ethnarch (milletbashi) of the Rum Millet, namely Greek Orthodox Christians within the Empire.

Mounting foreign incursions soon resulted in permanent settlement of Germanic and other ethnic groups into territories that became gradually autonomous, were sometimes acknowledged or even encouraged by treaty (foedus) by the Western Empire, and often embarked on expansion by further conquest.

As a consequence, when the last Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed by military commander Odoacer in 476, his direct rule did not extend much beyond the current Northern borders of Italy.

Meanwhile, Eastern Emperor Justinian I reestablished direct Imperial rule in Southern Spain, North Africa and especially Italy, reconquered during the hard-fought Gothic War (535–554).

Chris Wickham portrays the Visigothic king Euric (466–484) as "the first major ruler of a 'barbarian' polity in Gaul - the second in the Empire after Geiseric - to have a fully autonomous political practice, uninfluenced by any residual Roman loyalties.

Meanwhile, and for various reasons, Catholicism finally triumphed over Arianism in the Western kingdoms: in the Visigothic Iberian Peninsula with the conversion of Reccared I in 587, and in Lombard-held Italy, after some back-and-forth, following the death of King Rothari in 652.

This was in effect an act of triage: it strengthened the imperial grip in Southern Italy, but all but guaranteed the eventual destruction of the exarchate of Ravenna, which soon occurred at Lombard hands.

In 739, Gregory III sent a first embassy to Charles Martel seeking protection against Liutprand, King of the Lombards, but the Frankish strongman had been Liutbrand's ally in the past and had asked him in 737 to ceremonially adopt his son.

Pope Zachary was pressed into action by the final Lombard campaign against the exarchate of Ravenna, whose fall in mid-751 sealed the end of Byzantine rule in Central Italy.

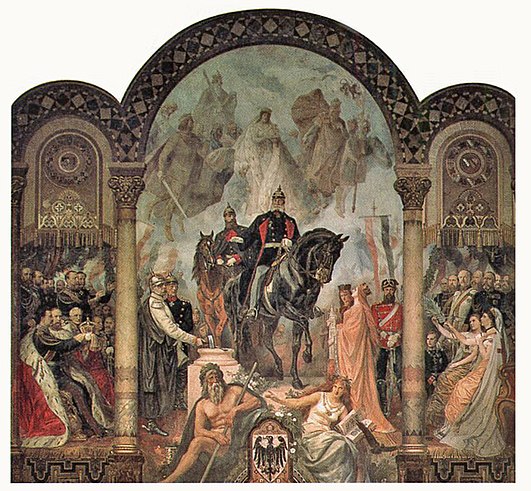

The coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III, in Rome on Christmas Day 800, was explicitly intended as establishing continuity with the Roman Empire that still existed in the East.

On Christmas Day 875, exactly 75 years after Charlemagne, Charles the Bald of West Francia was crowned Emperor in Rome by Pope John VIII, adopting the motto renovatio imperii Romani et Francorum, which raised the prospect of an Empire centered on what is today France.

Emperor Otto III reigned from Rome from 998 to his death in 1002, and made a short-lived attempt to revive ancient Roman institutions and traditions in partnership with Pope Sylvester II, who chose his papal name as an echo of the time of Constantine the Great.

Frederick II took a keen interest in Roman antiquity, sponsored archaeological excavations, organized a Roman-style triumph in Cremona in 1238 to celebrate his victory at the battle of Cortenuova, and had himself depicted in classical imagery.

According to his biographer Einhard, Charlemagne was unhappy about his coronation, a fact that later historians have interpreted as displeasure about the Pope's assumption of the key role in the legitimation of Imperial rule.

In 1527, the Pope's involvement in the Italian Wars led to the traumatic sack of Rome by Charles V's imperial troops, after which the Papacy's influence in international politics was significantly reduced.

Ivan III of Russia in 1472 married Sophia (Zoé) Palaiologina, a niece of the last Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI, and styled himself Tsar (Царь, "Caesar") or imperator.

This sequence of events supported the narrative, encouraged by successive rulers, that Muscovy was the rightful successor of Byzantium as the "Third Rome", based on a mix of religious (Orthodox), ethno-linguistic (East Slavic) and political ideas (the autocracy of the Tsar).

[68] and the manual of history of Edebé editorial (conservative nationalist) establishes a continuity between the Iberians, Rome, the Visigoths, and the peninsular Christian kingdoms as direct heirs of this Roman imperial tradition as Hispano-romans.

[81] For example, leading thinkers in British India saw the possibility to reconstruct the colony's education system and leave a legacy similar to that produced by the Romans in ancient Britain.

In the 20th century, several political thinkers and politicians have associated the multi-level governance and multilingualism of the Roman Empire in its various successive incarnations with the modern legal concepts of federalism and supranationalism.

According to that view, the EU, like other supranational endeavors such as the United Nations and World Bank, by attempting to revive the Roman Empire, signals the approaching end time, rapture or Second Coming.