Royal Cemetery at Ur

The Royal Cemetery at Ur is an archaeological site in modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate in southern Iraq.

The process was begun in 1922 by digging trial trenches, in order for the archaeologists to get an idea of the layout of the ancient city that would be documented in drawings by Katharine Woolley.

The Great Death Pit was an open square-shaped space, serving as the graveyard for the bodies of armed men that were laid out inside along with other corpses thought to belong to women or young girls.

He started the practice of such a massive entombment with the sacrifice of soldiers and an entire choir of women to accompany him in the afterlife.

Such a body belonged to Queen Puabi and was easy to identify due to her jewelry made out of beads of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and agate.

Nevertheless, the biggest clues that denoted her title as queen was a cylinder seal with her name on the inscription and her crown, which was made out of layers of gold ornaments shaped in intricate floral patterns.

Once more, Woolley uncovered an earth ramp leading down to the death pit of the well-preserved tomb, which was twelve by four meters approximately, and found a menagerie of corpses that ranged from armed men to women wearing headdresses with elaborate details.

In his descent toward the pit, he found traces of reed matting, and they covered the artifacts and bodies in order to avoid contact with the soil that had filled the royal grave.

Two meters below the level of the pit laid a tomb chamber built of stone that had no doorway in its walls, and its only accessible entrance was through its roof.

[3] The principal body was always laid on a mat made of reeds which also lined the floor and walls of the pit where the attendants are located.

Some tombs were found with male skeletons with helmets and spears positioned in front of the entrance as guards and then contained female attendants inside.

[5] Additionally, there is little textual evidence available to explain the tombs at the cemetery and the practices of the people but it is thought that the burials of the royalty consisted of multi-day ceremonies.

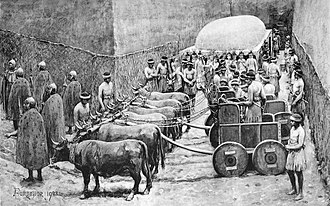

[6] In the next part of the ceremony the death pits were filled with guards, attendants, musicians, and animals, such as oxen or donkeys.

[3] Some research has found that some of the skulls had received blunt force trauma indicating that, rather than voluntarily serving their superiors in death, they were forcibly killed.

Many of these grave goods were likely imported from various surrounding regions including Afghanistan, Egypt, Ethiopia and the Indus valley.

[10] The various female personages and attendants buried at the cemetery of Ur were adorned with jewelry made from gold, silver, lapis lazuli and carnelian including a variety of necklaces, earrings, headdresses, and hair rings.

In addition, hair ribbons of gold and silver and inlaid combs with rosettes were also found amongst the human remains at Ur.

A gold helmet, whose ownership is attributed to Meskalamdug was found in a grave that Woolley believed to be an elite, but not necessarily a king.

Other examples of metal work include a variety of golden goblets and vessels made with handles of twisted wire.

Yet another lyre incorporated various materials including wood, shell, lapis lazuli, red stone, silver and gold.

These objects, referred to as "rams in the thicket" by Woolley, were made of wood and covered in gold, silver, shell and lapis lazuli.

[3] The Ram in a Thicket uses gold for the tree, legs, and face of the goat, silver for the belly and parts of the base alongside pink and white mosaics.

[3] The Standard of Ur is a trapezoidal wooden box incorporating lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone into the depiction of various figures on its surface.

On each side of the standard, the pictorial elements are considered part of a narrative sequence divided formally into 3 registers with all figures on a common ground.

Read from left to right, bottom to top on one side of the standard, starting with the lowest registers, there are men carrying various goods or leading animals and fish towards the top register where larger seated figures take part in a feast accompanied by musicians and attendants.

[16] Looting of archaeological sites was a common occurrence brought under control during the reign of Saddam Hussein, whose government declared the act a capital offense.

As a result, in 2008, a team of scholars, including Elizabeth Stone of Stony Brook University, found that the walls of the royal tombs were beginning to collapse.

Stone stated that for 30 years the "Iraq Department of Antiquities" lacked the resources to properly inspect and conserve the site, along with others that the team examined.

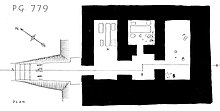

[38][39] PG 755 is a small individual grave without attendants, generally attributed to king Meskalamdug (𒈩𒌦𒄭, MES-KALAM-DUG[40] "hero of the good land")[41] Alternatively, since the tomb lacks of royal characteristics, it has been suggested that it may belong to a prince, for example the son of Meskalamdug.

[19] The tomb contained numerous gold artifacts including a golden helmet with an inscription of the king's name.