S-type granite

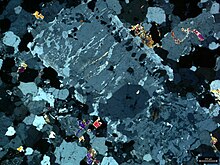

A photomicrograph, taken in cross-polarized light, of alkali feldspar from the S-type Strathbogie Granite of Australia is shown in figure 1.

[5] The S-type Granya Granite shows the characteristic white feldspars, grey quartz, and black biotite, the highly reflective mineral is muscovite.

Geologists use differences in mineralogy and texture, such as shown here, to subdivide large granite batholiths into subdomains on geologic maps.

[6] Minor minerals in S-type granites reflect the aluminium saturation or ASI Index of the rock being greater than 1.1 mol%.

The presence of these aluminous silicate minerals are commonly used as a means of initially classifying granites as “S-type”.

Photomicrographs of these minerals in thin section from S-type granites of the Lachlan Fold Belt are shown in figure 2a and 2b.

Figures 3a and 3b are photomicrographs of thin sections of sample CC-1 from the Cooma Granodiorite, Lachlan Fold Belt, Australia.

Accessory minerals commonly observed in S-type granites include zircon, apatite, tourmaline, monazite and xenotime.

Figures 5a and 5b are both in plane polarized light with the orientation of tourmaline rotated to show its characteristic change in color known as pleochroism.

Figure 6 is a plane polarized light photomicrograph showing apatite crystals (clear) included in a brown biotite grain from sample CV-126 of the Strathbogie Granite.

The dark circles with a clear center are pleochroic halos which form as the result of radiation damage to the biotite from mineral inclusions that contain high concentrations of uranium and/or thorium.

Alteration in S-type granites can produce, in order of abundance, chlorite, white mica, clay minerals, epidote, and sericite.

Change in crystal growth forms that are interpreted to occur as a result of this loss in pressure are known as "pressure-quenching" textures.

The interpretation of S-type granites are that they are sourced from the partial melting of sedimentary rocks (supracrustal) that have been through one or more cycles of weathering.

The I-S line is interpreted to be the location of a paleo-structure in the subsurface that separated the generation zones of the two different melts.

[9] This interpretation comes from the plotting of different element concentrations against the level of evolution of the granite, usually as percent silica or its magnesium to iron ratio.

Granites traced to the same source region can often have very variable mineralogy; color index for example can vary greatly within the same batholith.

More recent studies have shown that the source regions of I-type and S-type magmas cannot be homogeneously igneous or sedimentary, respectively.