Sauropoda

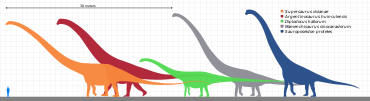

The holotype (and now lost) vertebra of Amphicoelias fragillimus (now Maraapunisaurus) may have come from an animal 58 metres (190 ft) long;[21] its vertebral column would have been substantially longer than that of the blue whale.

Meanwhile, 'mega-sauropods' such as Bruhathkayosaurus has long been scrutinized due to controversial debates on its validity, but recent photos re-surfacing in 2022 have legitimized it,[28] allowing for more updated estimates that range between 110–170 tons, rivaling the blue whale in size.

[32] Its small stature was probably the result of insular dwarfism occurring in a population of sauropods isolated on an island of the late Jurassic in what is now the Langenberg area of northern Germany.

[41] In titanosaurs, the ends of the metacarpal bones that contacted the ground were unusually broad and squared-off, and some specimens preserve the remains of soft tissue covering this area, suggesting that the front feet were rimmed with some kind of padding in these species.

Along with other saurischian dinosaurs (such as theropods, including birds), sauropods had a system of air sacs, evidenced by indentations and hollow cavities in most of their vertebrae that had been invaded by them.

A study by Michael D'Emic and his colleagues from Stony Brook University found that sauropods evolved high tooth replacement rates to keep up with their large appetites.

The dinosaurs' overall large body size and quadrupedal stance provided a stable base to support the neck, and the head was evolved to be very small and light, losing the ability to orally process food.

An air-sac system connected to the spaces not only lightened the long necks, but effectively increased the airflow through the trachea, helping the creatures to breathe in enough air.

By evolving vertebrae consisting of 60% air, the sauropods were able to minimize the amount of dense, heavy bone without sacrificing the ability to take sufficiently large breaths to fuel the entire body with oxygen.

[50] Another proposed function of the sauropods' long necks was essentially a radiator to deal with the extreme amount of heat produced from their large body mass.

It was in fact found that the increase in metabolic rate resulting from the sauropods' necks was slightly more than compensated for by the extra surface area from which heat could dissipate.

[54] This early notion was cast in doubt beginning in the 1950s, when a study by Kermack (1951) demonstrated that, if the animal were submerged in several metres of water, the pressure would be enough to fatally collapse the lungs and airway.

Henderson showed that such trackways can be explained by sauropods with long forelimbs (such as macronarians) floating in relatively shallow water deep enough to keep the shorter hind legs free of the bottom, and using the front limbs to punt forward.

[57] New studies published by Taia Wyenberg-henzler in 2022 suggest that sauropods in North America declined due to undetermined reasons in regards to their niches and distribution during the end of the Jurassic and into the latest Cretaceous.

It is also suggested in this same study that iguanodontians and hadrosauroids took advantage of recently vacated niches left by a decline in sauropod diversity during the late Jurassic and the Cretaceous in North America.

Some bone beds, for example a site from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina, appear to show herds made up of individuals of various age groups, mixing juveniles and adults.

[59] Since the segregation of juveniles and adults must have taken place soon after hatching, and combined with the fact that sauropod hatchlings were most likely precocial, Myers and Fiorillo concluded that species with age-segregated herds would not have exhibited much parental care.

[59] Multiple nesting sites discovered in Argentina and India contain 30-400 clutches of fossilized eggs that were found preserved, providing evidence of sauropod maternal care.

Researchers suggest that sauropods might have settled in nesting grounds close to volcanic activity for geothermal incubation, in which the mothers keep their eggs warm and isolated from predators.

[65] A skeletal mount depicting the diplodocid Barosaurus lentus rearing up on its hind legs at the American Museum of Natural History is one illustration of this hypothesis.

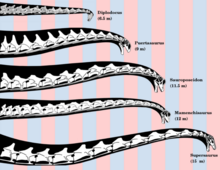

[72] However, research on living animals demonstrates that almost all extant tetrapods hold the base of their necks sharply flexed when alert, showing that any inference from bones about habitual "neutral postures"[72] is deeply unreliable.

In a study published in PLoS ONE on October 30, 2013, by Bill Sellers, Rodolfo Coria, Lee Margetts et al., Argentinosaurus was digitally reconstructed to test its locomotion for the first time.

The results of the biomechanics study revealed that Argentinosaurus was mechanically competent at a top speed of 2 m/s (5 mph) given the great weight of the animal and the strain that its joints were capable of bearing.

Many gigantic forms existed in the Late Jurassic (specifically Kimmeridgian), such as the turiasaur Turiasaurus, the mamenchisaurids Mamenchisaurus and Xinjiangtitan, the diplodocoids Maraapunisaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Supersaurus and Barosaurus, the camarasaurid Camarasaurus, and the brachiosaurids Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan.

Through the Early to Late Cretaceous, the giants Borealosaurus, Sauroposeidon, Paralititan, Argentinosaurus, Puertasaurus, Antarctosaurus, Dreadnoughtus, Notocolossus, Futalognkosaurus, Patagotitan and Alamosaurus lived, with all possibly being titanosaurs.

[51] One of the most extreme cases of island dwarfism is found in Europasaurus, a relative of the much larger Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus: it was only about 6.2 m (20 ft) long, an identifying trait of the species.

[32][51] Another taxon of tiny sauropods, the saltasaurid titanosaur Ibirania, 5.7 m (18.7 ft) long, lived a non-insular context in Upper Creaceous Brazil, and is an example of nanism resultant from other ecological pressures.

[91] Examination of the titanosaur's bones revealed what appear to be parasitic blood worms similar to the prehistoric Paleoleishmania but are 10-100 times larger, that seemed to have caused the osteomyelitis.

The group includes Tazoudasaurus and Vulcanodon, and the sister taxon Eusauropoda, but also certain species such as Antetonitrus, Gongxianosaurus and Isanosaurus that do not belong in Vulcanodontidae but to an even more basic position occupied in Sauropoda.

[105] Gravisauria split off in the Early Jurassic, around the Pliensbachian and Toarcian, 183 million years ago, and Aquesbi thought that this was part of a much larger revolution in the fauna, which includes the disappearance of Prosauropoda, Coelophysoidea and basal Thyreophora, which they attributed to a worldwide mass extinction.