School segregation in the United States

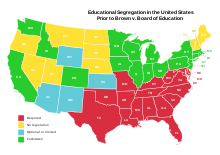

Segregation laws were met with resistance by Civil Rights activists and began to be challenged in 1954 by cases brought before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Segregation continued longstanding exclusionary policies in much of the Southern United States (where most African Americans lived) after the Civil War.

[4][5] Not only does the current segregation of neighborhoods and schools in the US affect social issues and practices, but it is considered by some to be a factor in the achievement gap between black and white students.

[5] Some authors such as Jerry Roziek and Ta-Nehisi Coates highlight the importance of tackling the root concept of racism instead of desegregation efforts that arise as a result of the end of de jure segregation.

Richard Humphreys, Samuel Powers Emlen Jr, and Prudence Crandall established schools for African Americans in the decades preceding the Civil War.

In 1835, an anti-abolitionist mob attacked and destroyed Noyes Academy, an integrated school in Canaan, New Hampshire founded by abolitionists in New England.

[18] The United States Supreme Court's Dred Scott v. Sandford decision upheld the denial of citizenship to African Americans and found that descendants of slaves are "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

[23] These restrictions in loans further separated black and white neighborhoods, which introduced the long term effects of residential segregation projects on schooling.

[26] Plessy v. Ferguson was overturned in 1954, when the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education ended de jure segregation in the United States.

[30] Desegregation efforts reached their peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the South transitioned from complete segregation to being the nation's most integrated region.

[31] Following the Great Depression, funding from the New Deal and legislation such as the 1934 Sugar Act enabled the creation of segregated schools for Mexican American children in Wyoming.

[34] Parents of both African-American and Mexican-American students challenged school segregation in coordination with civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, ACLU, and LULAC.

The NAACP initially challenged graduate and professional school segregation asserting that desegregation at this level would result in the least backlash and opposition by whites.

[37] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, when some states (including Alabama, Virginia, and Louisiana) closed their public schools to protest integration, Jerry Falwell Sr. took the opportunity to open "Christian academies" for white students.

[29] A 2013 study by Jeremy Fiel found that, "for the most part, compositional changes are to blame for the declining presence of whites in minorities' schools," and that racial balance increased from 1993 to 2010.

The deterioration of cities and urban education systems between the 1950-80s was the consequence of several post-war policies like the Home Owners' Loans Corporation, Federal Housing Administration, Interstate Highway Act, and discriminatory zoning practices.

The loss of war-time industrial employment perpetuated 'white flight' and suburban sprawl at the expense of poor, marginalized urban residents.

[43] Mid-20th century urban divestment and suburban development redirected social services and federal funding to predominantly white residencies.

Remaining urban residents witnessed dramatic decreases in quality of living, creating countless barriers to a stable life, including in academic success.

[44] In the 2005 Civil Rights Project conducted at Harvard University, researchers reported that over 80% of high-minority schools—where the student population is over 90% non-white—are high poverty schools as indicated by a large majority qualifying for free and reduced lunch.

[43] Researcher Peter Katel addressed the resegregation of schools as barriers for poor students in inner-city neighborhoods who are unprepared for higher education.

[46] Katel also reported that educational experts viewed high densities of marginalized students as a loss of funding that most white families do not experience, because they are more likely to have the capability to attend different schools.

The study found that segregation levels in school districts did not rise sharply following court dismissal, but rather increased gradually for the next 10 to 12 years.

[51] Such schools were initially presented as an alternative to unpopular busing policies, and included explicit desegregation goals along with provisions for recruiting and providing transportation for diverse populations.

[59] Integrated education is positively related to short-term outcomes such as K–12 school performance, cross-racial friendships, acceptance of cultural differences, and declines in racial fears and prejudice.

[61] Majority-minority schools present areas with high percentages of property that correspond to fewer resources and lower academic capability.

[62] A 1994 study found support for the theory that interracial contact in elementary or secondary school positively affects long-term outcomes in a way that can overcome perpetual segregation against black communities.

[63] This elimination has perpetuated itself into our current day school system, with statistics showing the number of black teachers as disproportionate to the student population.

According to the UCLA Civil Rights Project, a school district may consider race when using: "site selection of new schools; drawing attendance zones with general recognition of the racial demographics of neighborhoods; allocating resources for special programs; recruiting students and faculty in a targeted manner; [and] tracking enrollments, performance, and other statistics by race.

[50] Alternatively, states could move towards county- or region-level school districting, allowing students to be drawn from larger and more diverse geographic areas.