History of science and technology on the Indian subcontinent

[3] The size and prosperity of the Indus civilization grew as a result of this innovation, which eventually led to more planned settlements making use of drainage and sewerage.

[8] Modern oceanographers have observed that the Harappans must have possessed knowledge relating to tides in order to build such a dock on the ever-shifting course of the Sabarmati, as well as exemplary hydrography and maritime engineering.

[10] Based on archaeological and textual evidence, Joseph E. Schwartzberg (2008)—a University of Minnesota professor emeritus of geography—traces the origins of Indian cartography to the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2500–1900 BCE).

[12] The use of large scale constructional plans, cosmological drawings, and cartographic material was known in South Asia with some regularity since the Vedic period (2nd – 1st millennium BCE).

[13] Schwartzberg (2008)—on the subject of surviving maps—further holds that: "Though not numerous, a number of map-like graffiti appear among the thousands of Stone Age Indian cave paintings; and at least one complex Mesolithic diagram is believed to be a representation of the cosmos.

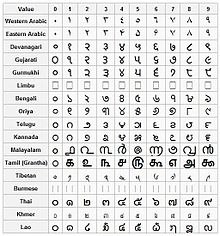

[20] For example, the mantra (sacrificial formula) at the end of the annahoma ("food-oblation rite") performed during the aśvamedha ("an allegory for a horse sacrifice"), and uttered just before-, during-, and just after sunrise, invokes powers of ten from a hundred to a trillion.

"[28] The Egyptian Papyrus of Kahun (1900 BCE) and literature of the Vedic period in India offer early records of veterinary medicine.

[30][31] However, The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine holds that the mention of leprosy, as well as ritualistic cures for it, were described in the Hindu religious book Atharvaveda, written in 1500–1200 BCE.

[37] Effective modern treatment was not developed until the early part of the 20th century when Canadians Frederick Banting and Charles Best isolated and purified insulin in 1921 and 1922.

[48] Some scholars believe that by the early 13th century BCE iron smelting was practiced on a bigger scale in India, suggesting that the date of the technology's inception may be placed earlier.

[59] Contact with the Greco-Roman world added newer techniques, and local artisans learnt methods of glass molding, decorating and coloring by the early centuries of the Common Era.

The Catuskoti is also often glossed Tetralemma (Greek), which is the name for a largely comparable, but not equatable, 'four corner argument' within the tradition of Classical logic.

[101] European scholar Francesco Lorenzo Pullè reproduced a number of Indian maps in his magnum opus La Cartografia Antica dell India.

[102] Samarangana Sutradhara, a Sanskrit treatise by Bhoja (11th century), includes a chapter about the construction of mechanical contrivances (automata), including mechanical bees and birds, fountains shaped like humans and animals, and male and female dolls that refilled oil lamps, danced, played instruments, and re-enacted scenes from Hindu mythology.

[103][104][105] Madhava of Sangamagrama (c. 1340 – 1425) and his Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics was the first to use infinite series approximations for a range of trigonometric functions and took decisive steps in analysis.

[108] The development of the series expansions for trigonometric functions (sine, cosine, and arc tangent) was carried out by mathematicians of the Kerala School in the 15th century CE.

According to Kisor Kumar Chakrabarti:[111] The Navya-Nyāya or Neo-Logical darśana (school) of Indian philosophy was founded in the 13th century CE by the philosopher Gangesha Upadhyaya of Mithila.

Other influences on Navya-Nyāya were the work of earlier philosophers Vācaspati Miśra (900–980 CE) and Udayana (late 10th century).Navya-Nyāya developed a sophisticated language and conceptual scheme that allowed it to raise, analyse, and solve problems in logic and epistemology.

It systematised all the Nyāya concepts into four main categories: sense or perception (pratyakşa), inference (anumāna), comparison or similarity (upamāna), and testimony (sound or word; śabda).

1520-1554) was a sixteenth century astronomer, astrologer, and mathematician from western India who wrote books on methods to predict eclipses, planetary conjunctions, positions, and make calculations for calendars.

[113] In 1500, Nilakantha Somayaji of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, in his Tantrasamgraha, revised Aryabhata's elliptical model for the planets Mercury and Venus.

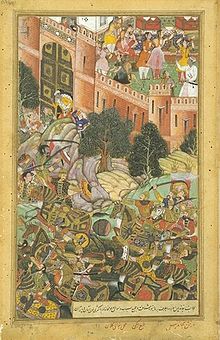

[116] It was written in the Tarikh-i Firishta (1606–1607) that the envoy of the Mongol ruler Hulegu Khan was presented with a pyrotechnics display upon his arrival in Delhi in 1258 CE.

[117] As a part of an embassy to India by Timurid leader Shah Rukh (1405–1447), 'Abd al-Razzaq mentioned naphtha-throwers mounted on elephants and a variety of pyrotechnics put on display.

[119] By the 16th century, South Asians were manufacturing a diverse variety of firearms; large guns in particular, became visible in Tanjore, Dacca, Bijapur and Murshidabad.

[124] The founder of the cashmere wool industry is believed traditionally held to be the 15th-century ruler of Kashmir, Zayn-ul-Abidin, who introduced weavers from Central Asia.

[125] According to Joseph E. Schwartzberg (2008): "The largest known Indian map, depicting the former Rajput capital at Amber in remarkable house-by-house detail, measures 661 × 645 cm.

"[126] Hyder Ali, prince of Mysore, developed war rockets with an important change: the use of metal cylinders to contain the combustion powder.

[127] According to Thomas Broughton, the Maharaja of Jodhpur sent daily offerings of fresh flowers from his capital to Nathadvara (320 km) and they arrived in time for the first religious Darshan at sunrise.

[131] The British education system, aimed at producing able civil and administrative services candidates, exposed a number of Indians to foreign institutions.

French astronomer, Pierre Janssen observed the Solar eclipse of 18 August 1868 and discovered helium, from Guntur in Madras State, British India.