Screw mechanism

The most common form consists of a cylindrical shaft with helical grooves or ridges called threads around the outside.

[4][5] Geometrically, a screw can be viewed as a narrow inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder.

The smaller the pitch (the distance between the screw's threads), the greater the mechanical advantage (the ratio of output to input force).

Other mechanisms that use the same principle, also called screws, do not necessarily have a shaft or threads.

The common principle of all screws is that a rotating helix can cause linear motion.

[10] Greek philosophers defined the screw as one of the simple machines and could calculate its (ideal) mechanical advantage.

[15] For example, Heron of Alexandria (52 AD) listed the screw as one of the five mechanisms that could "set a load in motion", defined it as an inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder, and described its fabrication and uses,[16] including describing a tap for cutting female screw threads.

[17] Because their complicated helical shape had to be laboriously cut by hand, screws were only used as linkages in a few machines in the ancient world.

Screw fasteners only began to be used in the 15th century in clocks, after screw-cutting lathes were developed.

[12] The complete dynamic theory of simple machines, including the screw, was worked out by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei in 1600 in Le Meccaniche ("On Mechanics").

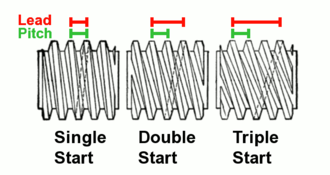

In these screws the lead is equal to the pitch multiplied by the number of starts.

[21][22] This is known as a right-handed (RH) thread, because it follows the right hand grip rule: when the fingers of the right hand are curled around the shaft in the direction of rotation, the thumb will point in the direction of motion of the shaft.

By common convention, right-handedness is the default handedness for screw threads.

Screw linkages in machines are exceptions; they can be right- or left-handed depending on which is more applicable.

Screw threads are standardized so that parts made by different manufacturers will mate correctly.

The greater the thread angle, the greater the angle between the load vector and the surface normal, so the larger the normal force between the threads required to support a given load.

The outward facing angled thread bearing surface, when acted on by the load force, also applies a radial (outward) force to the nut, causing tensile stress.

So the ideal mechanical advantage of a screw is equal to the distance ratio:

However most actual screws have large amounts of friction and their mechanical advantage is less than given by the above equation.

The mechanical advantage in this case can be calculated by using the length of the lever arm for r in the above equation.

This extraneous factor r can be removed from the above equation by writing it in terms of torque: Because of the large area of sliding contact between the moving and stationary threads, screws typically have large frictional energy losses.

Even well-lubricated jack screws have efficiencies of only 15% - 20%, the rest of the work applied in turning them is lost to friction.

When friction is included, the mechanical advantage is no longer equal to the distance ratio but also depends on the screw's efficiency.

[5] Large frictional forces cause most screws in practical use to be "self-locking", also called "non-reciprocal" or "non-overhauling".

This means that applying a torque to the shaft will cause it to turn, but no amount of axial load force against the shaft will cause it to turn back the other way, even if the applied torque is zero.

This is in contrast to some other simple machines which are "reciprocal" or "non locking" which means if the load force is great enough they will move backwards or "overhaul".

Most screws are designed to be self-locking, and in the absence of torque on the shaft will stay at whatever position they are left.

Other reasons for the screws to come loose are incorrect design of assembly and external forces such as shock, vibration and dynamic loads causing slipping on the threaded and mated/clamped surfaces.

Tightening the fastener by turning it puts compression force on the materials or parts being fastened together, but no amount of force from the parts will cause the screw to turn backwards and untighten.

[27][28][29] Whether a screw is self-locking ultimately depends on the pitch angle and the coefficient of friction of the threads; very well-lubricated, low friction threads with a large enough pitch may "overhaul".