Inclined plane

An inclined plane, also known as a ramp, is a flat supporting surface tilted at an angle from the vertical direction, with one end higher than the other, used as an aid for raising or lowering a load.

[4] The mechanical advantage of an inclined plane, the factor by which the force is reduced, is equal to the ratio of the length of the sloped surface to the height it spans.

Owing to conservation of energy, the same amount of mechanical energy (work) is required to lift a given object by a given vertical distance, disregarding losses from friction, but the inclined plane allows the same work to be done with a smaller force exerted over a greater distance.

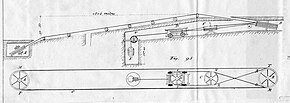

[5] The term may also refer to a specific implementation; a straight ramp cut into a steep hillside for transporting goods up and down the hill.

Aircraft evacuation slides allow people to rapidly and safely reach the ground from the height of a passenger airliner.

[14][15] The sloping roads and causeways built by ancient civilizations such as the Romans are examples of early inclined planes that have survived, and show that they understood the value of this device for moving things uphill.

The heavy stones used in ancient stone structures such as Stonehenge[16] are believed to have been moved and set in place using inclined planes made of earth,[17] although it is hard to find evidence of such temporary building ramps.

The Egyptian pyramids were constructed using inclined planes,[18][19][20] Siege ramps enabled ancient armies to surmount fortress walls.

The ancient Greeks constructed a paved ramp 6 km (3.7 miles) long, the Diolkos, to drag ships overland across the Isthmus of Corinth.

This is probably because it is a passive and motionless device (the load is the moving part),[21] and also because it is found in nature in the form of slopes and hills.

[22] This view persisted among a few later scientists; as late as 1826 Karl von Langsdorf wrote that an inclined plane "...is no more a machine than is the slope of a mountain".

[21] The problem of calculating the force required to push a weight up an inclined plane (its mechanical advantage) was attempted by Greek philosophers Heron of Alexandria (c. 10 - 60 CE) and Pappus of Alexandria (c. 290 - 350 CE), but their solutions were incorrect.

The first correct analysis of the inclined plane appeared in the work of 13th century author Jordanus de Nemore,[26][27] however his solution was apparently not communicated to other philosophers of the time.

[24] Girolamo Cardano (1570) proposed the incorrect solution that the input force is proportional to the angle of the plane.

[10] Then at the end of the 16th century, three correct solutions were published within ten years, by Michael Varro (1584), Simon Stevin (1586), and Galileo Galilei (1592).

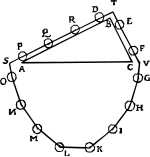

[24] Although it was not the first, the derivation of Flemish engineer Simon Stevin[25] is the most well-known, because of its originality and use of a string of beads (see box).

[28] The first elementary rules of sliding friction on an inclined plane were discovered by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), but remained unpublished in his notebooks.

[29] Leonhard Euler (1750) showed that the tangent of the angle of repose on an inclined plane is equal to the coefficient of friction.

[30] The mechanical advantage of an inclined plane depends on its slope, meaning its gradient or steepness.

A plane's slope s is equal to the difference in height between its two ends, or "rise", divided by its horizontal length, or "run".

Due to conservation of energy, for a frictionless inclined plane the work done on the load lifting it,

Substituting these values into the conservation of energy equation above and rearranging To express the mechanical advantage by the angle

from this equation is the force needed to hold the load motionless on the inclined plane, or push it up at a constant velocity.

Due to conservation of energy, the sum of the output work and the frictional energy losses is equal to the input work Therefore, more input force is required, and the mechanical advantage is lower, than if friction were not present.

the component of gravitational force parallel to the plane will be too small to overcome friction, and the load will remain motionless.

Since the direction of the frictional force is opposite for the case of uphill and downhill motion, these two cases must be considered separately: The mechanical advantage of an inclined plane is the ratio of the weight of the load on the ramp to the force required to pull it up the ramp.

If energy is not dissipated or stored in the movement of the load, then this mechanical advantage can be computed from the dimensions of the ramp.