Seabed gouging by ice

These result from spring run-off water flowing onto the surface of a given sea ice expanse, which eventually drains away through cracks, seal breathing holes, etc.

[10] Some discussion on the involvement of sea ice was brought up in the 1920s, but overall this phenomenon remained poorly studied by the scientific community up to the 1970s.

[11] At that time, ship-borne sidescan sonar surveys in the Canadian Beaufort Sea began to gather actual evidence of this mechanism.

What sparked the sudden interest for this phenomenon was the discovery of oil near Alaska's northern coastlines, and two related factors:[10] 1) the prospect that oilfields could abound in these waters, and 2) a consideration that submarine pipelines would be involved in future production developments, as this appeared to be the most practical approach to bring this resource to the shore.

This kind of information has been gathered by means of seabed mapping with ship-borne instrumentation, typically a fathometer: echo sounding devices such as a side-scan and a multi-beam sonar systems.

[20] Repetitive mapping involves repeating these surveys a number of times, at an interval ranging from a few to several years, as a means of estimating gouging frequency.

[24][25] The maximum water depths at which gouges have been reported range from 450 to 850 metres (1,480 to 2,790 ft), northwest of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean.

[26] These are thought to be remnant traces left by icebergs during the Pleistocene, thousands of years ago, when the sea level was lower than what it is today.

Recent episodes of grounding, gouging and fragmentation of large Antarctic icebergs have been observed to produce powerful hydroacoustic and seismic signals that further illuminate the dynamics of the process.

Stamukhi can penetrate the seabed to a considerable depth, and this also poses a risk to subsea pipelines at shore approaches.

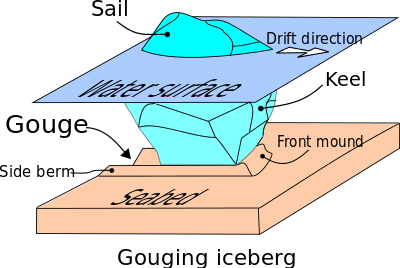

[35][36][37][38] Zone 1 is the gouge depth, where the soil has been displaced by the ice feature and remobilized into side berms and front mound ahead of the ice-seabed interface.

The area north of the Arctic Circle may hold a significant amount of undiscovered oil and gas, up to 13% and 30%, respectively, according to the USGS.

[42] An offshore production scheme necessarily aims for safe and economical operation throughout the year and the full lifespan of the project.

Offshore production developments often consist of installations on the seabed itself, away from sea surface hazards (wind, waves, ice).

Either way, if these installations include a submarine pipeline to deliver this resource to the shoreline, a substantial portion of its length could be exposed to gouging events.

For the currently operating North Star production site, “[t]he minimum pipeline depth of cover (original undisturbed seabed to top of pipe) to resist ice keel loads was calculated based on limit state design procedures for pipe bending”.

[45] This design philosophy must contend with at least three sources of uncertainty:[2] Oil and gas developments in Arctic waters must address environmental concerns through proper contingency plans.