Sebastianism

In Brazil the most important manifestation of Sebastianism took place in the context of the proclamation of the Republic, when movements defending a return to the monarchy emerged.

It is one of the longest-lived and most influential millenarian legends in Western Europe, having had profound political and cultural resonances from the time of Sebastian's death until at least the late 19th century in Brazil.

[1] King Sebastian of Portugal (January 20, 1554 – August 4, 1578) was the grandson of John III, and became heir to the throne due to the death of his father, Crown Prince João Manuel, two weeks before his birth.

Those who opposed the pretensions of Philip II of Spain to the throne of Portugal tended to support such versions of events, and backed the rule of King Henry or the claims of António, Prior of Crato, during the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

The body was, however, found to be in too advanced a state of decay shortly after its recovery to be definitively and conclusively confirmed as Sebastian, and was mostly rejected by Portuguese society as being his.

[3] After the death of King António, Dom João published a series of writings expounding the idea that King Sebastian was "the Hidden One", foretold to lead Portugal and all Christian nations in the unification of the Earth and the creation of one, last, Fifth Empire that was to succeed the four previous great earthly empires, based on the Book of Daniel, the Book of Revelation, and most importantly the messianic verses of António Gonçalves de Bandarra, written a few decades prior.

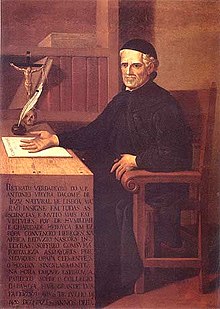

The verses of Bandarra influenced the Jesuit priest António Vieira, one the greatest literary figures in the history of the Portuguese-speaking world and an ardent supporter of King John IV.

[6] Accused of heresy, he was arrested by the Inquisition from October 1665 to December 1667, and finally imposed a sentence which prohibited him from teaching, writing or preaching.

The Inquisition condemned Sebastianism and actively sought to confiscate any writings associated with it, particularly the verses of Bandarra, in an effort to stamp out the belief, though with little success.

Some of the prophecies of Bandarra were seen as being confirmed particularly by the fact that marshal Junot ordered the universal extraction of taxes equally from every Portuguese individual, along with the resulting social unrest.

The Napoleonic invasions of Portugal motivated new editions of the verses of Bandarra, in 1809, prefaced by friar José Leonardo da Silva, in 1815 and 1822.

The second part of Mensagem, called Mar Português ("Portuguese Sea"), Pessoa references Portugal's Age of Exploration and its seaborne empire until the death of King Sebastian in 1578.

Many Portuguese folk tales, particularly in the Azores, feature King Sebastian, usually riding a white horse, and sometimes followed by companions.

Within two years, as the religious community prospered, Conselheiro convinced several thousand followers to join him, eventually making it the second-largest urban center in Bahia at the time.

A popular tune sung by minstrels among the community went that "Dom Sebastião has arrived/And he brings many directives/Abolishing the civil union/And conducting marriage./Our King Sebastian/Shall visit us/Regret be on the poor man/Who is [married] under dogs law.

[19] In 1893 the community entered into conflict with the magistrate of a neighbouring town, which spun into an ultimately violent confrontation with the state that became the deadliest civil-war in Brazilian history, known as the War of Canudos.

Conselheiro perished amidst the fighting and the community was violently razed at the end of a fourth military expedition sent against it, with over 25,000 people being estimated to have been killed.