Second Bulgarian Empire

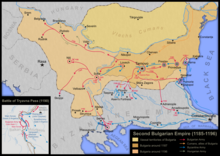

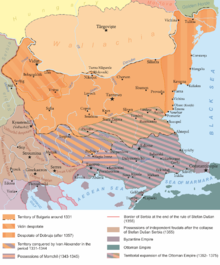

[6] A successor to the First Bulgarian Empire,[7][8][9][10] it reached the peak of its power under Tsars Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II before gradually being conquered by the Ottomans in the late 14th century.

[26] In 1185, two aristocrat brothers from Tarnovo, Theodore and Asen, asked the emperor to provide them a relatively poor pronoia in the Balkan Mountains, in exchange for military service.

Ivan Asen's strategy of swiftly striking in different locations paid off, and he soon took control of the important cities Sofia and Niš to the south-west, clearing the way to Macedonia.

[48] While the Bulgarians were occupied in the south, the Hungarian king Andrew II and his Serbian vassal Vukan had annexed Belgrade, Braničevo, and Niš, but after negotiating peace, Kaloyan turned his attention to the north-west.

[64][65][66] Ivan Asen II released all ordinary soldiers and marched on the Epirote–controlled territories, where all cities and towns from Adrianople to Durazzo on the Adriatic Sea surrendered and recognized his rule.

The weakness of the new government was exposed when the Nicaean army conquered large areas in southern Thrace, the Rhodopes, and Macedonia—including Adrianople, Tsepina, Stanimaka, Melnik, Serres, Skopje, and Ohrid—meeting little resistance.

[77][78] This major setback cost the emperor's life and led to a period of instability and civil war between several claimants to the throne until 1257, when the boyar of Skopje Constantine Tikh emerged as a victor.

[85][86] Fearing a revolt in Byzantium, and willing to exploit the situation, the emperor Michael VIII sent an army led by Ivan Asen III, a Bulgarian pretender to the throne, but the rebels reached Tarnovo first.

After the Byzantines failed, Michael VIII turned to the Mongols, who invaded Dobrudzha and defeated Ivaylo's army, forcing him to retreat to Drastar, where he withstood a three-month siege.

[92] In 1300, Theodore Svetoslav, George I's eldest son, took advantage of a civil war in the Golden Horde, overthrew Chaka, and presented his head to the Mongol khan Toqta.

[93] The new emperor began to rebuild the country's economy, subdued many of the semi-independent nobles, and executed as traitors those he held responsible for assisting the Mongols, including Patriarch Joachim III.

[94][95][96] The Byzantines, interested in Bulgaria's continuous instability, supported pretenders Michael and Radoslav with their armies, but were defeated by Theodore Svetoslav's uncle Aldimir, the despot of Kran.

The two rulers, both expecting reinforcements, agreed to a one-day truce but when a Catalan detachment under the king's son Stephen Dušan arrived, the Serbs broke their word.

That acquisition marked the last significant territorial expansion of medieval Bulgaria, but also led to the first attacks on Bulgarian soil by the Ottoman Turks, who were allied with Kantakouzenos.

[112] In 1366, Ivan Alexander refused to grant passage to the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos, and the troops of the Savoyard crusade attacked the Bulgarian Black Sea coast.

They immediately turned on Bulgaria and conquered northern Thrace, the Rhodopes, Kostenets, Ihtiman, and Samokov, effectively limiting the authority of Ivan Shishman in the lands to the north of the Balkan mountains and the Valley of Sofia.

[117] Unable to resist, the Bulgarian monarch was forced to become an Ottoman vassal, and in return he recovered some of the lost towns and secured ten years of uneasy peace.

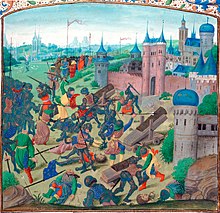

[125] In 1396, Ivan Sratsimir joined the Crusade of the Hungarian king Sigismund, but after the Christian army was defeated in the Battle of Nicopolis the Ottomans immediately marched on Vidin and seized it, bringing an end to the medieval Bulgarian state.

During wartime, the Bulgarians would send light cavalry to devastate the enemy lands on a broad front, pillaging villages and small towns, burning the crops, and taking people and cattle.

[147] Inside the fortress [Sofia] there is a large and elite army, its soldiers are heavily built, moustached and look war-hardened, but are used to consume wine and rakia—in a word, jolly fellows.

In 1355, the Ecumenical patriarch Callistus I tried to assert his supremacy over the Bulgarian church and claimed that under the provisions of the Council of Lampsacus it remained subordinated and had to pay annual tribute to Constantinople.

At its height under the reign of Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–41), it consisted of 14 dioceses; Preslav, Cherven, Lovech, Sofia, Ovech, Drastar, Vidin, Serres, Philippi, Messembria, Braničevo, Belgrade, Niš, and Velbazhd; and the sees of Tarnovo and Ohrid.

[182][181] Hesychasm (from Greek "stillness, rest, quiet, silence") is an eremitic tradition of prayer in the Eastern Orthodox Church that flourished in the Balkans during the 14th century.

In 1335, he gave refuge to Gregory of Sinai and provided funds for the construction of a monastery near Paroria in the Strandzha Mountains in the southeast of the country; it attracted clerics from Bulgaria, Byzantium, and Serbia.

[204] The Church of the Holy Mother of God in Donja Kamenica in the western part of the Bulgarian Empire (in modern Serbia) is notable for its unusual architectural style.

Despite being influenced by some tendencies of the Palaeogan Renaissance in the Byzantine Empire, Bulgarian painting had unique features; it was first classified as a separate artistic school by the French art historian André Grabar.

[209] The frescoes in the Boyana Church near Sofia are an early example of the painting of the Tarnovo Artistic School, dating from 1259; they are among the most complete and best-preserved monuments of Eastern European medieval art.

[209] Fragments of frescoes were excavated in the ruins of the seventeen churches in Tarnovo's second fortified hill, Trapezitsa; among them were depictions of military figures wearing richly decorated garments.

[221] Two poems, written by a Byzantine poet in the court in Tarnovo and dedicated to the wedding of emperor Ivan Asen II and Irene Komnene Doukaina, have survived.

[224] The Ottoman conquest of Bulgaria forced many scholars and disciples of Euthymius to emigrate, taking their texts, ideas, and talents to other Orthodox countries—Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and the Russian principalities.