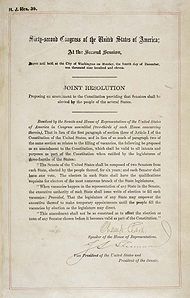

Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

It also alters the procedure for filling vacancies in the Senate, allowing for state legislatures to permit their governors to make temporary appointments until a special election can be held.

[7] Additionally, the longer terms and avoidance of popular election turned the Senate into a body that could counter the populism of the House.

While the representatives operated in a two-year direct election cycle, making them frequently accountable to their constituents, the senators could afford to "take a more detached view of issues coming before Congress".

It was hoped they would provide abler deliberation and greater stability than the House of Representatives due to the senators' status.

[11] Those in favor of popular elections for senators believed two primary problems were caused by the original provisions: legislative corruption and electoral deadlocks.

[12] There was a sense that senatorial elections were "bought and sold", changing hands for favors and sums of money rather than because of the competence of the candidate.

But conservative analysts Bybee and Todd Zywicki believe this concern was largely unfounded; there was a "dearth of hard information" on the subject.

[16] The tipping point came in 1865 with the election of John P. Stockton (D-NJ), which happened after the New Jersey legislature changed its rules regarding the definition of a quorum and was thus by plurality instead of by absolute majority.

If no person received a majority, the joint assembly was required to keep convening every day to take at least one vote until a senator was elected.

[20] The business of holding elections also caused great disruption in the state legislatures, with a full third of the Oregon House of Representatives choosing not to swear the oath of office in 1897 due to a dispute over an open Senate seat.

In a deadlock situation, state legislatures would deal with the matter by holding "one vote at the beginning of the day—then the legislators would continue with their normal affairs".

[25] Similar amendments were introduced in 1829 and 1855, with the "most prominent" proponent being Andrew Johnson, who raised the issue in 1868 and considered the idea's merits "so palpable" that no additional explanation was necessary.

In reaction, the Congress passed a bill in July 1866 that required state legislatures to elect senators by an absolute majority.

[30] On the second national legislative front, reformers worked toward a constitutional amendment, which was strongly supported in the House of Representatives but initially opposed by the Senate.

[29] Reformers included William Jennings Bryan, while opponents counted respected figures such as Elihu Root and George Frisbie Hoar among their number; Root cared so strongly about the issue that after the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment he refused to stand for re‑election to the Senate.

[12] Bryan and the reformers argued for popular election through highlighting flaws they saw within the existing system, specifically corruption and electoral deadlocks, and through arousing populist sentiment.

[32] The reform was considered by opponents to threaten the rights and independence of the states, who were "sovereign, entitled ... to have a separate branch of Congress ... to which they could send their ambassadors."

The Seventeenth Amendment altered the process for electing United States senators and changed the way vacancies would be filled.

[48] Before the Supreme Court required "one man, one vote" in Reynolds v. Sims (1964), malapportionment of state legislatures was common.

With direct election, each vote represented equally, the Democrats held their stronghold in the South and offset net Republican gains in the Northeast by picking up new seats in New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, retaining control of the Senate.

[50] The reputation of corrupt and arbitrary state legislatures continued to decline as the Senate joined the House of Representatives in implementing popular reforms.

Bybee has argued that the amendment led to complete "ignominy" for state legislatures without the buttress of a state-based check on Congress.

[56] It also allows a state's legislature to permit its governor to make temporary appointments, which last until a special election is held to fill the vacancy.

[58] Oregon held primaries in 1908 in which the parties would run candidates for that position, and the state legislature pledged to choose the winner as the new senator.

The first direct elections to the Senate following the Seventeenth Amendment being adopted were:[58] In Trinsey v. Pennsylvania (1991),[60] the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit was faced with a situation where, following the death of Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania, Governor Bob Casey had provided for a replacement and for a special election that did not include a primary.

[65] Sanford Levinson, in his rebuttal to Amar, argues that rather than engaging in a textual interpretation, those examining the meaning of constitutional provisions should interpret them in the fashion that provides the most benefit, and that legislatures' being able to restrict gubernatorial appointment authority provides a substantial benefit to the states.

[67] Some members of the Tea Party movement argued for repealing the Seventeenth Amendment entirely, claiming it would protect states' rights and reduce the power of the federal government.

[69] On July 28, 2017, after Republican senators John McCain, Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski voted against the Health Care Freedom Act, which would have repealed the Affordable Care Act, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee endorsed the repeal of the Seventeenth Amendment.

[72] In September 2020, Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska endorsed the repeal of the Seventeenth Amendment in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece.