Shape

It is distinct from other object properties, such as color, texture, or material type.

In geometry, shape excludes information about the object's position, size, orientation and chirality.

For instance, polygons are classified according to their number of edges as triangles, quadrilaterals, pentagons, etc.

Each of these is divided into smaller categories; triangles can be equilateral, isosceles, obtuse, acute, scalene, etc.

Other common shapes are points, lines, planes, and conic sections such as ellipses, circles, and parabolas.

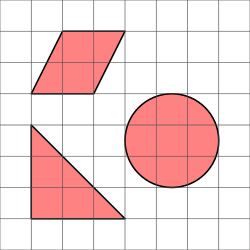

Such shapes are called polygons and include triangles, squares, and pentagons.

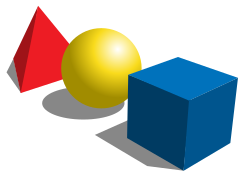

Many three-dimensional geometric shapes can be defined by a set of vertices, lines connecting the vertices, and two-dimensional faces enclosed by those lines, as well as the resulting interior points.

Such shapes are called polyhedrons and include cubes as well as pyramids such as tetrahedrons.

Other three-dimensional shapes may be bounded by curved surfaces, such as the ellipsoid and the sphere.

For instance, the letters "b" and "d" are a reflection of each other, and hence they are congruent and similar, but in some contexts they are not regarded as having the same shape.

Sometimes, only the outline or external boundary of the object is considered to determine its shape.

In advanced mathematics, quasi-isometry can be used as a criterion to state that two shapes are approximately the same.

Simple shapes can often be classified into basic geometric objects such as a line, a curve, a plane, a plane figure (e.g. square or circle), or a solid figure (e.g. cube or sphere).

Some, such as plant structures and coastlines, may be so complicated as to defy traditional mathematical description – in which case they may be analyzed by differential geometry, or as fractals.

Some common shapes include: Circle, Square, Triangle, Rectangle, Oval, Star (polygon), Rhombus, Semicircle.

Regular polygons starting at pentagon follow the naming convention of the Greek derived prefix with '-gon' suffix: Pentagon, Hexagon, Heptagon, Octagon, Nonagon, Decagon... See polygon In geometry, two subsets of a Euclidean space have the same shape if one can be transformed to the other by a combination of translations, rotations (together also called rigid transformations), and uniform scalings.

In other words, the shape of a set of points is all the geometrical information that is invariant to translations, rotations, and size changes.

[...] We here define ‘shape’ informally as ‘all the geometrical information that remains when location, scale[3] and rotational effects are filtered out from an object.’Shapes of physical objects are equal if the subsets of space these objects occupy satisfy the definition above.

For instance, a "d" and a "p" have the same shape, as they can be perfectly superimposed if the "d" is translated to the right by a given distance, rotated upside down and magnified by a given factor (see Procrustes superimposition for details).

For instance, a "b" and a "p" have a different shape, at least when they are constrained to move within a two-dimensional space like the page on which they are written.

Even though they have the same size, there's no way to perfectly superimpose them by translating and rotating them along the page.

For example, a sphere becomes an ellipsoid when scaled differently in the vertical and horizontal directions.

An object is therefore congruent to its mirror image (even if it is not symmetric), but not to a scaled version.

A more flexible definition of shape takes into consideration the fact that realistic shapes are often deformable, e.g. a person in different postures, a tree bending in the wind or a hand with different finger positions.

Roughly speaking, a homeomorphism is a continuous stretching and bending of an object into a new shape.

These shapes can be classified using complex numbers u, v, w for the vertices, in a method advanced by J.A.

For example, an equilateral triangle can be expressed by the complex numbers 0, 1, (1 + i√3)/2 representing its vertices.

The shape p = S(u,v,w) depends on the order of the arguments of function S, but permutations lead to related values.

[6] Human vision relies on a wide range of shape representations.

[7][8] Some psychologists have theorized that humans mentally break down images into simple geometric shapes (e.g., cones and spheres) called geons.