Islamic finance products, services and contracts

Benefits that will follow from banning interest and obeying "divine injunctions"[32] include an Islamic economy free of "imbalances" (Taqi Usmani)[32]—concentration of "wealth in the hands of the few", or monopolies which paralyze or hinder market forces, etc.—a "move towards economic development, creation of the value added factor, increased exports, less imports, job creation, rehabilitation of the incapacitated and training of capable elements" (Saleh Abdullah Kamel).

Nizam Yaquby, for example declares that the "guiding principles" for Islamic finance include: "fairness, justice, equality, transparency, and the pursuit of social harmony".

[39] Zubair Hasan argues that the objectives of Islamic finance as envisaged by its pioneers were "promotion of growth with equity ... the alleviation of poverty ... [and] a long run vision to improve the condition of the Muslim communities across the world.

[66][67][68][69] In many Islamic banks asset portfolios, short term financing, notably murabaha and other debt-based contracts account for the great bulk of their investments.

[84] However, at least one critic (M. A. El-Gamal) complains that this violates the sharia principle that banks must charge 'rent' (or lease payment) based on comparable rents for the asset being paid off, not "benchmarked to commercial interest rate[s]".

)[92] This is despite the fact that (according to Uthmani) "Shari‘ah supervisory Boards are unanimous on the point that [Murabahah loans] are not ideal modes of financing", and should be used when more preferable means of finance—"musharakah, mudarabah, salam or istisna'—are not workable for some reasons".

Unlike conventional financing, the bank is compensated for the time value of its money in the form of "profit" not interest,[90] and any penalties for late payment go to charity, not to the financier.

[62] However, according to another (Bangladeshi) source, Bai' muajjal differs from Murabahah in that the client, not the bank, is in possession of and bear the risk for the goods being purchased before completion of payment.

According to the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, it "serves as a ruse for lending on interest",[102] but Bai' al inah is practised in Malaysia and similar jurisdictions.

[103][104] Bai al inah is not accepted in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) but in 2009 the Malaysian Court of Appeals upheld it as a shariah-compliant technique.

In traditional fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), it means a contract for the hiring of persons or services or "usufruct" of a property generally for a fixed period and price.

[129] An example would be in an automobile financing facility, a customer enters into the first contract and leases the car from the owner (bank) at an agreed amount over a specific period.

(This type of transaction is similar to the contractum trinius, a legal maneuver used by European bankers and merchants during the Middle Ages to sidestep the Church's prohibition on interest bearing loans.

In a contractum, two parties would enter into three (trinius) concurrent and interrelated legal contracts, the net effect being the paying of a fee for the use of money for the term of the loan.

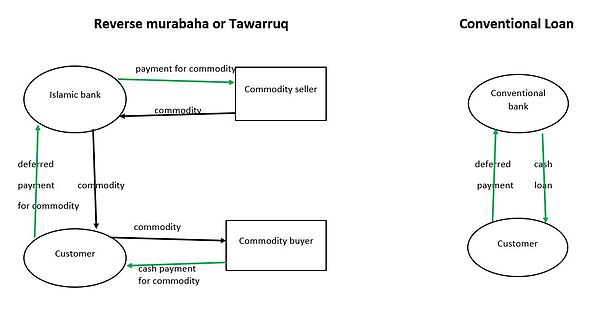

)[140] While tawarruq strongly resembles a cash loan—something forbidden under orthodox Islamic law—and its greater complexity (like bai' al inah mentioned above) mean higher costs than a conventional bank loan, proponents argue the tangible assets that underlie the transactions give it sharia compliance.

Hawaladars networks are often based on membership in the same family, village, clan, or ethnic group, and cheating is punished by effective ex-communication and "loss of honour"—leading to severe economic hardship.

[165] A Wakalah is a contract where a person (the principal or muwakkel)[167] appoints a representative (the agent or wakil) to undertake transactions on his/her behalf, similar to a power of attorney.

[168] The agent's services may include selling and buying, lending and borrowing, debt assignment, guarantee, gifting, litigation and making payments, and are involved in numerous Islamic products like Musharakah, Mudarabah, Murabaha, Salam and Ijarah.

[171] From the point of view of depositors, "Investment accounts" of Islamic banks—based on profit and loss sharing and asset-backed finance—resemble "time deposits" of conventional banks.

[183] This puts account holders in the curious position—according to one skeptic (M. O. Farooq)—of making charitable loans with their deposits to multi-million or billion dollar profit-making banks, who are obliged by jurisprudence (in theory) to "repay" (i.e. to honor customers' withdrawals) only if and when able.

[57] In Iran, qard al-hasanah deposit accounts are permitted to provide a number of incentives in lieu of interest, including: Like dividends on shares of stock, hibah cannot be stipulated or legally guaranteed in Islam, and is not time bound.

[185] Nonetheless, one scholar (Mohammad Hashim Kamali) has complained: "If Islamic banks routinely announce a return as a 'gift' for the account holder or offer other advantages in the form of services for attracting deposits, this would clearly permit entry of riba through the back door.

Abdullah and Chee, refer to amanah as a type of wadiah—Wadiah yad amanah—that is property deposited on the basis of trust or guaranteeing safe custody[195] and must be kept in the banks vaults.

However, in practice, most sukuk are "asset-based" rather than "asset-backed"—their assets are not truly owned by their Special Purpose Vehicle, and (like conventional bonds), their holders have recourse to the originator if there is a shortfall in payments.

Omar Fisher and Dawood Y. Taylor state that takaful has "reinvigorate[d] human capital, emphasize[d] personal dignity, community self-help, and economic self-development".

[243] Tahawwut has not being widely used as of 2015, according to Harris Irfan, as the market is "awash" with "unique, bespoke ... contracts documenting the profit rate swap", all using "roughly the same structure", but differing in details and preventing the cost saving of standardization.

[238] Some critics (like Feisal Khan and El-Gamal) complain it uses a work-around (requiring a "down-payment" towards the shorted stock) that is no different than "margin" regulations for short-selling used in at least one major country (the US), but entails "substantially higher fees" than conventional funds.

[257] In 2007, Yusuf DeLorenzo (chief sharia officer at Shariah Capital) issued a fatwa disapproving of the double wa'd[258] in these situations (when the assets reflected in the benchmark were not halal),[259] but this has not curtailed its use.

(Many of them also among the estimated 72 percent of the Muslim population who do not use formal financial services,[264] often either because they are not available, and/or because potential customer believe conventional lending products incompatible with Islamic law).

"[267] An earlier 2008 study of 126 microfinance institutions in 14 Muslim countries[272] found similarly weak outreach—only 380,000 members[Note 18] out of an estimated total population of 77 million there were "22 million active borrowers" of non-sharia-compliant microfinance institutions ("Grameen Bank, BRAC, and ASA") as of 2011 in Bangladesh, the largest sharia-compliant MFI or bank in that country had only 100,000 active borrowers.