Fall of Tenochtitlan

[10] Under pressure by his relatives, who had a different leader in mind, Velázquez revoked Cortés's mandate to lead the expedition before the man left Cuba.

[citation needed] But after reaching Mexico, Cortés used the same legal tactic as had been used by Governor Velázquez when he invaded Cuba years before: he created a local government and had himself elected as the magistrate.

As he encountered several polities who resented Aztec rule, Cortés told them he had arrived on orders of his Emperor to improve conditions, abolish human sacrifices, teach the locals the true faith, and "stop them from robbing each other".

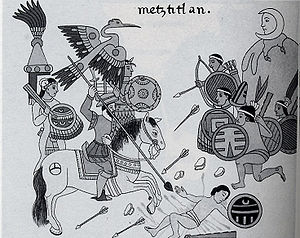

Before entering the city, on November 8, 1519, Cortés and his troops prepared for battle by armoring themselves and their horses, and arranging into military rank with four leading horsemen followed by five contingents of foot soldiers.

It is possible he feared losing his life or political power; however, one of the effective threats wielded by Cortés was the destruction of the city in the case of fighting between Spaniards and Aztecs (which ultimately came to pass).

As Moctezuma complied with orders issued by Cortés, such as commanding tribute to be gathered and given to the Spaniards, his authority was slipping, and quickly his people began to turn against him.

[17] After Cortés became aware of their arrival, he left Pedro de Alvarado in charge in Tenochtitlan with 80 soldiers, and brought all his forces (about two hundred and forty men) by quick marches to Narváez's camp in Cempohuallan on May 27.

Cortés then completed winning over Narváez's captains with promises of the vast wealth in Tenochtitlan, inducing them to follow him back to the Aztec capital.

[18] At this time, the Mexica (Aztecs) began to prepare for the annual festival of Toxcatl in early May, in honor of Tezcatlipoca, otherwise known as the Smoking Mirror or the Omnipotent Power.

The direct loss of nearly a hundred men dead and the fierce spirit of the Aztecs who refused to be cowed by his ascent of the temple convinced Cortés that a night escape was now his only option for survival.

Approximately a third of the Spaniards succeeded in reaching the mainland, while the others died in battle or were captured and later sacrificed on Aztec altars - these were reported to be mostly the followers of Narváez, less experienced and more weighted down with gold, which was handed out freely before the escape.

[2][page needed] Before reaching Tlaxcala, the scanty Spanish forces arrived at the plain of Otumba Valley (Otompan), where they were met by a vast Aztec army intent on their destruction.

Here, the Aztecs made their own errors of judgement by underestimating the shock value of the Spanish caballeros because all they had seen was the horses traveling gingerly on the wet paved streets of Tenochtitlan.

[28][page needed] Despite the overwhelming numbers of Aztecs and the generally poor condition of the Spanish survivors, Cortés snatched victory from the jaws of defeat.

Cano, another primary source, gives 1,150 Spaniards dead, though this figure was likely too high and might encompass the total loss from entering Mexico to arriving into Tlaxcala.

They expected the Spanish to pay for their supplies, to have the city of Cholula, an equal share of any of the spoils, the right to build a citadel in Tenochtitlan, and finally, to be exempted from any future tribute.

After Cortés' forces managed to defeat the smaller armies of some Aztec tributary states, Tepeyac, and later, Yauhtepec and Cuauhnahuac were easily won over.

[2][page needed] While Cortés was rebuilding his alliances and garnering more supplies, a smallpox epidemic struck the natives of the Valley of Mexico, including Tenochtitlan.

[2][page needed] Smallpox played a crucial role in the Spanish success during the Siege of Tenochtitlan from 1519 to 1521, a fact not mentioned in some historical accounts.

[31][page needed] While the population of Tenochtitlan was recovering, the disease continued to Chalco, a city on the southeast corner of Lake Texcoco that was formerly controlled by the Aztecs but now occupied by the Spanish.

[12] Reproduction and population growth declined since people of child-bearing age either had to fight off the Spanish invasion or died due to famine, malnutrition or other diseases.

As the only Aztec victory against the Spanish was won in the city using their peculiar urban warfare tactics, and as they counted on retaining control over the water, it seems natural that they wanted to risk their main army only to defend their capital.

However, it would not be correct to infer that the Aztecs were passive observers of their fate - they did send numerous expeditions to aid their allies against Cortés at every point, with 10 to 20 thousand forces risked in every engagement, such as in Chalco and Chapultepec.

Cortés intended to do that primarily by increasing his power and mobility on the lake, while protecting "his flanks while they marched up the causeway", previously one of his main weaknesses.

He had planned to attack on the causeways during the daytime and retreat to camp at night; however, the Aztecs moved in to occupy the abandoned bridges and barricades as soon as the Spanish forces left.

[34]: 379–83 Díaz relates, "...the dismal drum of Huichilobos sounded again,...we saw our comrades who had been captured in Cortés' defeat being dragged up the steps to be sacrificed...cutting open their chests, drew out their palpitating hearts which they offered to the idols...the Indian butchers...cut off their arms and legs...then they ate their flesh with a sauce of peppers and tomatoes...throwing their trunks and entrails to the lions and tigers and serpents and snakes."

Alvarado's company made it there first, and Gutierrez de Badajoz advanced to the top of the Huichilopotzli cu, setting it afire and planting their Spanish banners.

[37] The American historian Charles Robinson wrote: "Centuries of hate and the basic viciousness of Mesoamerican warfare combined in violence that appalled Cortés himself".

"[34]: 409–10, 412 Cuauhtémoc was taken prisoner the same day, as related above, and remained the titular leader of Tenochtitlan, under the control of Cortés, until he was hanged for treason in 1525 while accompanying a Spanish expedition to Guatemala.

[39] Due to the wholesale slaughter after the campaign and the destruction of Aztec culture many sources such as Israel Charney,[40] John C. Cox,[41] and Norman Naimark[39] consider the siege a genocide.