Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

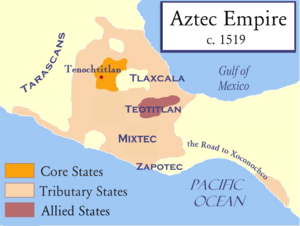

Taking place between 1519 and 1521, this event saw the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, and his small army of European soldiers and numerous indigenous allies, overthrowing one of the most powerful empires in Mesoamerica.

[8] A combination of factors including superior weaponry, strategic alliances with oppressed or otherwise dissatisfied or opportunistic indigenous groups, and the impact of European diseases contributed to the downfall of the short rule of the Aztec civilization.

After eight months of battles and negotiations, which overcame the diplomatic resistance of the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II to his visit, Cortés arrived in Tenochtitlan on 8 November 1519, where he took up residence with fellow Spaniards and their indigenous allies.

"[17] The integration of the indigenous allies, essentially, those from Tlaxcala and Texcoco, into the Spanish army played a crucial role in the conquest, yet other factors paved the path for the Spaniards' success.

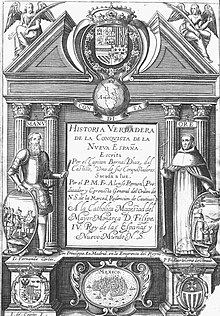

Bernal Díaz's account had begun as a benemérito petition for rewards but he expanded it to encompass a full history of his earlier expeditions in the Caribbean and Tierra Firme and the conquest of the Aztec.

[37] The chronicle of the so-called "Anonymous Conqueror" was written sometime in the sixteenth century, entitled in an early twentieth-century translation to English as Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan (i.e. Tenochtitlan).

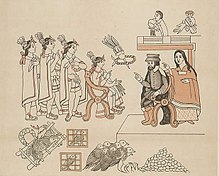

[40] The best-known indigenous account of the conquest is Book 12 of Bernardino de Sahagún's General History of the Things of New Spain and published as the Florentine Codex, in parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish, with pictorials.

Less well-known is Sahagún's 1585 revision of the conquest account, which shifts from the indigenous viewpoint entirely and inserts at crucial junctures passages lauding the Spanish and in particular Hernán Cortés.

[44] Not surprisingly, many publications and republications of sixteenth-century accounts of the conquest of Mexico appeared around 1992, the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's first voyage, when scholarly and popular interest in first encounters surged.

"[46] In the sources recorded by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún and Dominican Diego Durán in the mid to late sixteenth century, there are accounts of events that were interpreted as supernatural omens of the conquest.

The native texts of the defeated Mexica narrating their version of the conquest describe eight omens that were believed to have occurred nine years prior to the arrival of the Spanish from the Gulf of Mexico.

[citation needed] In 1517, Cuban governor Diego Velázquez commissioned a fleet of three ships under the command of Hernández de Córdoba to sail west and explore the Yucatán peninsula.

With the help of tens of thousands of Xiu Mayan warriors, it would take more than 170 years for the Spanish to establish full control of the Maya homelands, which extended from northern Yucatán to the central lowlands region of El Petén and the southern Guatemalan highlands.

In an agreement signed on 23 October 1518, Governor Velázquez restricted the expedition led by Cortés to exploration and trade, so that conquest and settlement of the mainland might occur under his own command, once he had received the permission necessary to do so which he had already requested from the Crown.

[49]: 49, 51, 55–56 Cortés's contingent consisted of 11 ships carrying about 630 men (including 30 crossbowmen and 12 arquebusiers, an early form of firearm), a doctor, several carpenters, at least eight women, a few hundred Arawaks from Cuba and some Africans, both freedmen and slaves.

Although modern usage often calls the European participants "soldiers", the term was never used by these men themselves in any context, something that James Lockhart realized when analyzing sixteenth-century legal records from conquest-era Peru.

[65] Although Guerrero's later fate is somewhat uncertain, it appears that for some years he continued to fight alongside the Maya forces against Spanish incursions, providing military counsel and encouraging resistance; it is speculated that he may have been killed in a later battle.

To ensure the legality of this action, several members of his expedition, including Francisco Montejo and Alonso Hernandez Puertocarrero, returned to Spain to seek acceptance of the cabildo's declaration with King Charles.

[75] Meanwhile, Moctezuma's ambassadors, who had been in the Spanish camp after the battles with the Tlaxcalans, continued to press Cortés to take the road to Mexico via Cholula, which was under Aztec control, rather than over Huexotzinco, which was an ally of Tlaxcala.

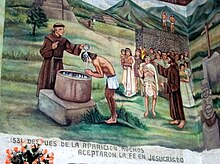

"[49]: 218, 242 Cortés later asked Moctezuma to allow him to erect a cross and an image of Virgin Mary next to the two large idols of Huichilobos and Tezcatlipoca, after climbing the one hundred and fourteen steps to the top of the main temple pyramid, a central place for religious authority.

Cortés along with five of his captains and Doña Marina and Aguilar, convinced Moctezuma to "come quietly with us to our quarters, and make no protest ... if you cry out, or raise any commotion, you will immediately be killed."

[49]: 247 In April 1520, Cortés was told by Moctezuma that a much larger party of Spanish troops had arrived, consisting of nineteen ships and fourteen hundred soldiers under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez.

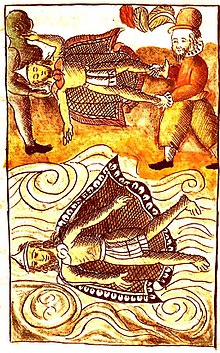

[49]: 282–84 [clarification needed] Cortés led his combined forces on an arduous trek back over the Sierra Madre Oriental, returning to Mexico on St. John's Day June 1520, with 1,300 soldiers and 96 horses, plus 2,000 Tlaxcalan warriors.

Human sacrifice and reports of cannibalism, common among the natives of the Aztec Empire, had been a major reason motivating Cortés and encouraging his soldiers to avoid surrender while fighting to the death.

Mendoza was entirely loyal to the Spanish crown, unlike the conqueror of Mexico Hernán Cortés, who had demonstrated that he was independent-minded and defied official orders when he threw off the authority of Governor Velázquez in Cuba.

A major work that utilizes colonial-era indigenous texts as its main source is James Lockhart's The Nahuas After the Conquest: Postconquest Central Mexican History and Philology.

The Spanish crown via the Council of the Indies and the Franciscan order in the late sixteenth century became increasingly hostile to works in the indigenous languages written by priests and clerics, concerned that they were heretical and an impediment to the Indians' true conversion.

The Manila Galleon brought in far more silver direct from South American mines to China than the overland Silk Road, or even European trade routes in the Indian Ocean could.

As a result of these unions, as well as concubinage [citation needed] and secret mistresses, mixed race individuals known as mestizos became the majority of the Mexican population in the centuries following the Spanish conquest.

The expedition was also partially included in the animated film The Road to El Dorado as the main characters Tulio and Miguel end up as stowaways on Hernán Cortés' fleet to Mexico.