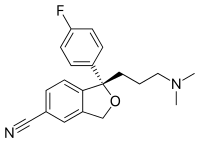

Skeletal formula

Skeletal formulae have become ubiquitous in organic chemistry, partly because they are relatively quick and simple to draw, and also because the curved arrow notation used for discussions of reaction mechanisms and electron delocalization can be readily superimposed.

For example, conformational structures look similar to skeletal formulae and are used to depict the approximate positions of atoms in 3D space, as a perspective drawing.

However, there are slight differences in the conventions used, and the reader needs to be aware of them in order to understand the structural details encoded in the depiction.

Heteroatoms and functional groups are collectively called "substituents", as they are considered to be a substitute for the hydrogen atom that would be present in the parent hydrocarbon of the organic compound.

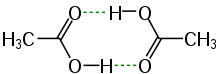

However, the skeletal formula is understood to represent the "real molecule" – that is, the weighted average of all contributing canonical forms.

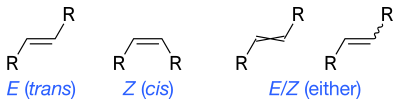

A few minor conventional variations, especially with respect to the use of stereobonds, continue to exist as a result of differing US, UK and European practice, or as a matter of personal preference.

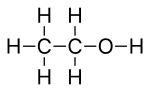

All atoms that are not carbon or hydrogen are signified by their chemical symbol, for instance Cl for chlorine, O for oxygen, Na for sodium, and so forth.

In the context of organic chemistry, these atoms are commonly known as heteroatoms (the prefix hetero- comes from Greek ἕτερος héteros, meaning "other").

[4] A list of common pseudoelement symbols: Sulfonate esters are often leaving groups in nucleophilic substitution reactions.

In these cases, a combination of solid and dashed lines indicate the integer and non-integer parts of the bond order, respectively.

In recent years, benzene is generally depicted as a hexagon with alternating single and double bonds, much like the structure Kekulé originally proposed in 1872.

This style, based on one proposed by Johannes Thiele, used to be very common in introductory organic chemistry textbooks and is still frequently used in informal settings.

The modern solid and hashed wedges were introduced in the 1940s by Giulio Natta to represent the structure of high polymers, and extensively popularised in the 1959 textbook Organic Chemistry by Donald J. Cram and George S.

Wavy single bonds are the standard way to represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers (as with tetrahedral stereocenters).