Eusociality

A colony has caste differences: queens and reproductive males take the roles of the sole reproducers, while soldiers and workers work together to create and maintain a living situation favorable for the brood.

[1][2] Batra observed the cooperative behavior of the bees, males and females alike, as they took responsibility for at least one duty (i.e., burrowing, cell construction, oviposition) within the colony.

[8][9] Eusociality has evolved multiple times in different insect orders, including hymenopterans,[10] termites,[11] thrips,[12] aphids,[12] and beetles.

[13] The order Hymenoptera contains the largest group of eusocial insects, including ants, bees, and wasps—divided into castes: reproductive queens, drones, more or less sterile workers, and sometimes also soldiers that perform specialized tasks.

Between approximately 0–40 days old, the workers perform tasks within the nest such as provisioning cell broods, colony cleaning, and nectar reception and dehydration.

S. regalis, S. microneptunus, S. filidigitus, S. elizabethae, S. chacei, S. riosi, S. duffyi, and S. cayoneptunus are the eight recorded species of parasitic shrimp that rely on fortress defense and live in groups of closely related individuals in tropical reefs and sponges.

[33] They live eusocially with a single breeding female, and a large number of male defenders armed with enlarged snapping claws.

They are found in the highest numbers in the basal visceral mass, where competing trematodes tend to multiply during the early phase of infection.

This strategic positioning allows them to effectively defend against invaders, similar to how soldier distribution patterns are seen in other animals with defensive castes.

[41] Usually living in harsh or limiting environments, these mole-rats aid in raising siblings and relatives born to a single reproductive queen.

[45] Edward O. Wilson called humans eusocial apes, arguing for similarities to ants, and observing that early hominins cooperated to rear their children while other members of the same group hunted and foraged.

[55][56] This would mean that humans sometimes exhibit a type of alloparental behavior known as "helpers at the nest", with juveniles and sexually mature adolescents helping their parents raise subsequent broods, as in some birds,[57] some non-eusocial bees, and meerkats.

[59][48][60] One plant, the epiphytic staghorn fern, Platycerium bifurcatum (Polypodiaceae), may exhibit a primitive form of eusocial behavior amongst clones.

In On the Origin of Species, Darwin referred to the existence of sterile castes as the "one special difficulty, which at first appeared to me insuperable, and actually fatal to my theory".

After the gene-centered view of evolution was developed in the mid-1970s, non-reproductive individuals were seen as an extended phenotype of the genes, which are the primary beneficiaries of natural selection.

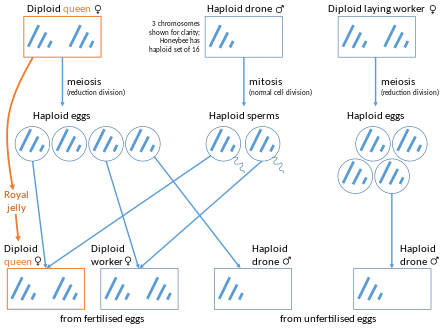

This mechanism of sex determination gives rise to what W. D. Hamilton first termed "supersisters", more closely related to their sisters than they would be to their own offspring.

This unusual situation, where females may have greater fitness when they help rear sisters rather than producing offspring, is often invoked to explain the multiple independent evolutions of eusociality (at least nine separate times) within the Hymenoptera.

Conversely, many non-eusocial bees are haplodiploid, and among eusocial species many queens mate with multiple males, resulting in a hive of half-sisters that share only 25% of their genes.

[73] If kin selection is an important force driving the evolution of eusociality, monogamy should be the ancestral state, because it maximizes the relatedness of colony members.

Group living affords colony members defense against enemies, specifically predators, parasites, and competitors, and allows them to gain advantage from superior foraging methods.

[7] The importance of ecology in the evolution of eusociality is supported by evidence such as experimentally induced reproductive division of labor, for example when normally solitary queens are forced together.

[76] Similarly, social transitions within halictid bees, where eusociality has been gained and lost multiple times, are correlated with periods of climatic warming.

[78] Once pre-adaptations such as group formation, nest building, high cost of dispersal, and morphological variation are present, between-group competition has been suggested as a driver of the transition to advanced eusociality.

The "point of no return" hypothesis posits that the morphological differentiation of reproductive and non-reproductive castes prevents highly eusocial species such as the honeybee from reverting to the solitary state.

[84] The levels of two of the aliphatic compounds increase rapidly in virgin queens within the first week after emergence from the pupa, consistent with their roles as sex attractants during the mating flight.

[83] Similarly, queen weaver ants Oecophylla longinoda have exocrine glands that produce pheromones which prevent workers from laying reproductive eggs.

[85] The mode of action of inhibitory pheromones which prevent the development of eggs in workers has been demonstrated in the bumble bee Bombus terrestris.

[84] A variety of other mechanisms give queens of different species of social insects a measure of reproductive control over their nest mates.

This jelly contains a specific protein, royalactin, which increases body size, promotes ovary development, and shortens the developmental time period.

[87] Stephen Baxter's 2003 science fiction novel Coalescent imagines a human eusocial organisation founded in ancient Rome, in which most individuals are subject to reproductive repression.