Non-rocket spacelaunch

Non-rocket spacelaunch refers to theoretical concepts for launch into space where much of the speed and altitude needed to achieve orbit is provided by a propulsion technique that is not subject to the limits of the rocket equation.

Due to the exponential nature of the rocket equation, providing even a small amount of the velocity to LEO by other means has the potential of greatly reducing the cost of getting to orbit.

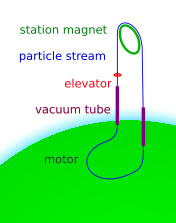

[citation needed] Endo-atmospheric tethers can be used to transfer kinetics (energy and momentum) between large conventional aircraft (subsonic or low supersonic) or other motive force and smaller aerodynamic vehicles, propelling them to hypersonic velocities without exotic propulsion systems.

[citation needed] A skyhook is a theoretical class of orbiting tether propulsion intended to lift payloads to high altitudes and speeds.

[34] Its main component is a ribbon-like cable (also called a tether) anchored to the surface and extending into space above the level of geosynchronous orbit.

With conventional materials, the taper ratio would need to be very large, increasing the total launch mass to a fiscally infeasible degree.

For locations in the Solar System with weaker gravity than Earth's (such as the Moon or Mars), the strength-to-density requirements aren't as great for tether materials.

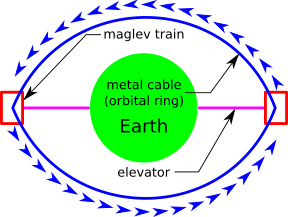

[37] In a series of 1982 articles published in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society,[13] Paul Birch presented the concept of orbital ring systems.

In 1982 the Belarusian inventor Anatoly Yunitskiy also proposed an electromagnetic track encircling the Earth, which he called the "String Transportation System."

[39] One proposed design is a freestanding tower composed of high strength material (e.g. kevlar) tubular columns inflated with a low density gas mix, and with dynamic stabilization systems including gyroscopes and "pressure balancing".

In order to achieve orbit, the projectile must be given enough extra velocity to punch through the atmosphere, unless it includes an additional propulsion system (such as a rocket).

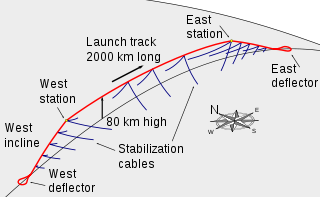

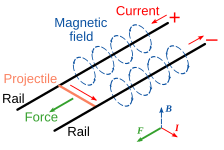

In essence, a mass driver is a very long and mainly horizontally aligned launch track or tunnel for accelerating payloads to orbital or suborbital velocities.

The concept was proposed by Arthur C. Clarke in 1950,[41] and was developed in more detail by Gerard K. O'Neill, working with the Space Studies Institute, focusing on the use of a mass driver for launching material from the Moon.

In pneumatic launch systems, a projectile is accelerated in a long tube by air pressure, produced by ground-based turbines or other means.

The projectile, which is shaped like a ram jet core, is fired by another means (e.g., a space gun, discussed above) supersonically through the first diaphragm into the end of the tube.

In a slingatron,[23][44] projectiles are accelerated along a rigid tube or track that typically has circular or spiral turns, or combinations of these geometries in two or three dimensions.

A slingatron is capable of much higher velocities than a similar circular launcher based on a rotating tether made of currently available materials (e.g. Dyneema).

In his initial paper, Dr. Derek A. Tidman, the slingatron's inventor, assumed that, to eliminate friction, the projectile would have to be supported by magnetic levitation in an evacuated tube.

He predicted that most of the energy lost to friction would go to vaporizing the ablator rather than eroding the guide tube, allowing the slingatron to compare favorably with light gas guns in terms of barrel wear.

Nor can the amplitude of the track's gyrating motion be increased to compensate, as it suffers from the same tip velocity limitation as the simple rotating tether.

But according to Tidman's analysis, a slingatron launching 1 lb (454 g) projectiles at 6 km/s (about 80% of orbital velocity) could be as small as 11.2 meters across, [45] though at over 10,000 rpm, such a launcher would need to have a gyration speed faster than some hard drives.

[46] American aerospace company SpinLaunch is developing a kinetic energy launch system that accelerates the payload on the arm of a vacuum-sealed centrifuge to before hurling it to space at up to 4,700 mph (7,500 km/h; 2.1 km/s).

The rocket then ignites its engines at an altitude of roughly 200,000 ft (60 km) to reach orbital speed of 17,150 mph (27,600 km/h; 7.666 km/s) with a payload of up to 200kg.

A Spanish company, zero2infinity, is officially developing a launcher system called bloostar based on the rockoon concept, expected to be operational by 2018.

In 2010, NASA suggested that a future scramjet aircraft might be accelerated to 300 m/s (a solution to the problem of ramjet engines not being startable at zero airflow velocity) by electromagnetic or other sled launch assist, in turn air-launching a second-stage rocket delivering a satellite to orbit.

[54] All forms of projectile launchers are at least partially hybrid systems if launching to low Earth orbit, due to the requirement for orbit circularization, at a minimum entailing approximately 1.5 percent of the total delta-v to raise perigee (e.g. a tiny rocket burn), or in some concepts much more from a rocket thruster to ease ground accelerator development.

[55] Forms of ground launch limited to a given maximum acceleration (such as due to human g-force tolerances if intended to carry passengers) have the corresponding minimum launcher length scale not linearly but with velocity squared.

For instance, for anticipated practicality and a moderate mass ratio with current materials, the HASTOL concept would have the first half (4 km/s) of velocity to orbit be provided by other means than the tether itself.

For instance, the number of parts in a liquid-fueled rocket engine may be two orders of magnitude less if pressure-fed rather than pump-fed if its delta-v requirements are limited enough to make the weight penalty of such be a practical option, or a high-velocity ground launcher may be able to use a relatively moderate performance and inexpensive solid fuel or hybrid small motor on its projectile.

Though suborbital, the first private crewed spaceship, SpaceShipOne had reduced rocket performance requirements due to being a combined system with its air launch.