Spanish phonology

Other accents of Spanish, comprising the majority of speakers, have lost the palatal lateral as a distinct phoneme and have merged historical /ʎ/ into /ʝ/: this is called yeísmo.

In Rioplatense Spanish, spoken across Argentina and Uruguay, the voiced palato-alveolar fricative [ʒ] is used in place of [ʝ] and [ʎ], a feature called "zheísmo".

[16] However, speakers in parts of southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and all of Latin America lack this distinction, merging both consonants as /s/.

[25][14][26][27][28][29][30] In some Extremaduran, western Andalusian, and American varieties, this softened realization of /f/, when it occurs before the non-syllabic allophone of /u/ ([w]), is subject to merger with /x/; in some areas the homophony of fuego/juego is resolved by replacing fuego with lumbre or candela.

[34] An exception to coda nasal place assimilation is the sequence /mn/ that can be found in the middle of words such as alumno, columna, himno.

The tap is found in words where no morpheme boundary separates the obstruent from the following rhotic consonant, such as sobre 'over', madre 'mother', ministro 'minister'.

[52] The tap/trill alternation has prompted a number of authors to postulate a single underlying rhotic; the intervocalic contrast then results from gemination (e.g. tierra /ˈtieɾɾa/ > [ˈtjera] 'earth').

[17] In one region of Spain, the area around Madrid, word-final /d/ is sometimes pronounced [θ], especially in a colloquial pronunciation of the city's name, Madriz ([maˈðɾiθ]ⓘ).

So the clusters -bt- and -pt- in the words obtener and optimista are pronounced exactly the same way: Similarly, the spellings -dm- and -tm- are often merged in pronunciation, as well as -gd- and -cd-: Traditionally, the palatal consonant phoneme /ʝ/ is considered to occur only as a syllable onset,[62] whereas the palatal glide [j] that can be found after an onset consonant in words like bien is analyzed as a non-syllabic version of the vowel phoneme /i/[63] (which forms part of the syllable nucleus, being pronounced with the following vowel as a rising diphthong).

The approximant allophone of /ʝ/, which can be transcribed as [ʝ˕], differs phonetically from [j] in the following respects: [ʝ˕] has a lower F2 amplitude, is longer, can be replaced by a palatal fricative [ʝ] in emphatic pronunciations, and is unspecified for rounding (e.g. viuda [ˈbjuða]ⓘ 'widow' vs. ayuda [aˈʝʷuða]ⓘ 'help').

[8] A contrast is therefore possible after any consonant that can end a syllable, as illustrated by the following minimal or near-minimal pairs: after /l/ (italiano [itaˈljano] 'Italian' vs. y tal llano [italˈɟʝano] 'and such a plain'[8]), after /n/ (enyesar [eɲɟʝeˈsaɾ]ⓘ 'to plaster' vs. aniego [aˈnjeɣo]ⓘ 'flood'[10]) after /s/ (desierto /deˈsieɾto/ 'desert' vs. deshielo /desˈʝelo/ 'thawing'[8]), after /b/ (abierto /aˈbieɾto/ 'open' vs. abyecto /abˈʝeɡto/ 'abject'[8][64]).

[65] In Argentine Spanish, the change of /ʝ/ to a fricative realized as [ʒ ~ ʃ] has resulted in clear contrast between this consonant and the glide [j]; the latter occurs as a result of spelling pronunciation in words spelled with ⟨hi⟩, such as hierba [ˈjeɾβa] 'grass' (which thus forms a minimal pair in Argentine Spanish with the doublet yerba [ˈʒeɾβa] 'maté leaves').

[71] There is no surface phonemic distinction between close-mid and open-mid vowels, unlike in Catalan, Galician, French, Italian and Portuguese.

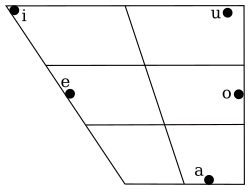

[75] Because of substratal Quechua, at least some speakers from southern Colombia down through Peru can be analyzed to have only three vowel phonemes /i, u, a/, as the close [i, u] are continually confused with the mid [e, o], resulting in pronunciations such as [dolˈsoɾa] for dulzura ('sweetness').

[clarification needed] When Quechua-dominant bilinguals have /e, o/ in their phonemic inventory, they realize them as [ɪ, ʊ], which are heard by outsiders as variants of /i, u/.

According to him, the exact degree of openness of Spanish vowels depends not so much on the phonetic environment but rather on various external factors accompanying speech.

[102] This can be summarized as follows (parentheses enclose optional components): The following restrictions apply: Maximal onsets include transporte /tɾansˈpor.te/, flaco /ˈfla.ko/, clave /ˈkla.be/.

Because of the phonotactic constraints, an epenthetic /e/ is inserted before word-initial clusters beginning with /s/ (e.g. escribir 'to write') but not word-internally (transcribir 'to transcribe'),[119] thereby moving the initial /s/ to a separate syllable.

[122] Occasionally Spanish speakers are faced with onset clusters containing elements of equal or near-equal sonority, such as Knoll (a German last name that is common in parts of South America).

The attempted trill sound of the poor trillers is often perceived as a series of taps owing to hyperactive tongue movement during production.

While the distinction between these two sounds has traditionally been a feature of Castilian Spanish, this merger has spread throughout most of Spain in recent generations, particularly outside of regions in close linguistic contact with Catalan and Basque.

[146] In Spanish America, most dialects are characterized by this merger, with the distinction persisting mostly in parts of Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and northwestern Argentina.

[9] The phoneme /s/ has three different pronunciations depending on the dialect area:[9][42][149] Obaid describes the apico-alveolar sound as follows:[152] There is a Castilian s, which is a voiceless, concave, apicoalveolar fricative: the tip of the tongue turned upward forms a narrow opening against the alveoli of the upper incisors.

It resembles a faint /ʃ/ and is found throughout much of the northern half of Spain.Dalbor describes the apico-dental sound as follows:[153] [s̄] is a voiceless, corono-dentoalveolar groove fricative, the so-called s coronal or s plana because of the relatively flat shape of the tongue body ... To this writer, the coronal [s̄], heard throughout Andalusia, should be characterized by such terms as "soft," "fuzzy," or "imprecise," which, as we shall see, brings it quite close to one variety of /θ/ ... Canfield has referred, quite correctly, in our opinion, to this [s̄] as "the lisping coronal-dental," and Amado Alonso remarks how close it is to the post-dental [θ̦], suggesting a combined symbol ⟨θˢ̣⟩ to represent it.In some dialects, /s/ may become the approximant [ɹ] in the syllable coda (e.g. doscientos [doɹˈθjentos] 'two hundred').

In parts of southern Spain, the only feature defined for /s/ appears to be voiceless; it may lose its oral articulation entirely to become [h] or even a geminate with the following consonant ([ˈmihmo] or [ˈmimːo] from /ˈmismo/ 'same').

Similarly, a number of coda assimilations occur: Final /d/ dropping (e.g. mitad [miˈta] 'half') is general in most dialects of Spanish, even in formal speech.

[162] The deletions and neutralizations show variability in their occurrence, even with the same speaker in the same utterance, so non-deleted forms exist in the underlying structure.

[164] Guitart (1997) argues that it is the result of speakers acquiring multiple phonological systems with uneven control like that of second language learners.

Entonces decidieron que el más fuerte sería quien lograse despojar al viajero de su abrigo.

Esto hizo que el viajero sintiera calor y por ello se quitó su abrigo.