Spice trade

Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in the Eastern World.

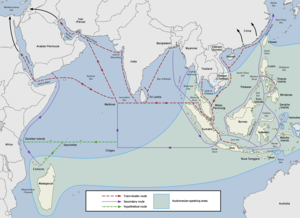

By this period, trade routes existed from Sri Lanka (the Roman Taprobane) and India, which had acquired maritime technology from early Austronesian contact.

People from the Neolithic period traded in spices, obsidian, sea shells, precious stones and other high-value materials as early as the 10th millennium BC.

In the 3rd millennium BC, they traded with the Land of Punt, which is believed to have been situated in an area encompassing northern Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea and the Red Sea coast of Sudan.

Indonesians in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the westerlies in the Indian Ocean.

This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD.

[11][12][10][13][14][15][16][17] In the first millennium BC the Arabs, Phoenicians, and Indians were also engaged in sea and land trade in luxury goods such as spices, gold, precious stones, leather of exotic animals, ebony and pearls.

There is a record from Tamil texts of Greeks purchasing large sacks of black pepper from India, and many recipes in the 1st-century Roman cookbook Apicius make use of the spice.

[1] The rise of Islam brought a significant change to the trade as Radhanite Jewish and Arab merchants, particularly from Egypt, eventually took over conveying goods via the Levant to Europe.

The islands of cloves are called Maluku ....."[23] Moluccan products were shipped to trading emporiums in India, passing through ports like Kozhikode in Kerala and through Sri Lanka.

[25] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.

[25] Indian spice exports find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).

[1] Until the mid-15th century, trade with the East was achieved through the Silk Road, with the Byzantine Empire and the Italian city-states of Venice and Genoa acting as middlemen.

Emboldened by these early successes and eyeing a lucrative monopoly on a possible sea route to the Indies, the Portuguese first rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 on an expedition led by Bartolomeu Dias.

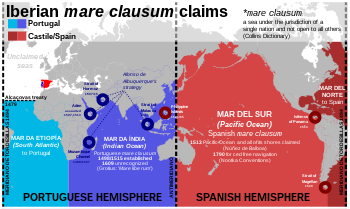

After Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama in 1513, the Spanish Crown prepared a westward voyage by Ferdinand Magellan in order to reach Asia from Spain across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

After Magellan's death in the Philippines, navigator Juan Sebastian Elcano took command of the expedition and drove it across the Indian Ocean and back to Spain, where they arrived in 1522 aboard the last remaining ship, the Victoria.

A global spice route had been created: from Manila in the Philippines (Asia) to Seville in Spain (Europe), via Acapulco in Mexico (North America).

[31] They include bananas,[32] Pacific domesticated coconuts,[33][34] Dioscorea yams,[35] wetland rice,[32] sandalwood,[36] giant taro,[37] Polynesian arrowroot,[38] ginger,[39] lengkuas,[31] tailed pepper,[40] betel,[12] areca nut,[12] and sugarcane.

[44] Islam spread throughout the East, reaching maritime Southeast Asia in the 10th century; Muslim merchants played a crucial part in the trade.

[46] The Portuguese colonial settlements saw traders, such as the Gujarati banias, South Indian Chettis, Syrian Christians, Chinese from Fujian province, and Arabs from Aden, involved in the spice trade.

[50] Conversely, Southeast Asian cuisine and crops was also introduced to India and Sri Lanka, where rice cakes and coconut milk-based dishes are still dominant.

[52] Indian food, adapted to the European palate, became visible in England by 1811 as exclusive establishments began catering to the tastes of both the curious and those returning from India.