Alternative splicing

In the case of protein-coding genes, the proteins translated from these splice variants may contain differences in their amino acid sequence and in their biological functions (see Figure).

Biologically relevant alternative splicing occurs as a normal phenomenon in eukaryotes, where it increases the number of proteins that can be encoded by the genome.

In addition, the primary transcript contained multiple polyadenylation sites, giving different 3' ends for the processed mRNAs.

[7] The gene encoding the thyroid hormone calcitonin was found to be alternatively spliced in mammalian cells.

Both of these mechanisms are found in combination with alternative splicing and provide additional variety in mRNAs derived from a gene.

[1] Splicing is regulated by trans-acting proteins (repressors and activators) and corresponding cis-acting regulatory sites (silencers and enhancers) on the pre-mRNA.

[23][24] There are two major types of cis-acting RNA sequence elements present in pre-mRNAs and they have corresponding trans-acting RNA-binding proteins.

The majority of splicing repressors are heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) such as hnRNPA1 and polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB).

As another example, a cis-acting element can have opposite effects on splicing, depending on which proteins are expressed in the cell (e.g., neuronal versus non-neuronal PTB).

The intron upstream from exon 4 has a polypyrimidine tract that doesn't match the consensus sequence well, so that U2AF proteins bind poorly to it without assistance from splicing activators.

The resulting mRNA encodes an active Tra protein, which itself is a regulator of alternative splicing of other sex-related genes (see dsx above).

An mRNA including exon 6 encodes the membrane-bound form of the Fas receptor, which promotes apoptosis, or programmed cell death.

In this particular case, these exon definition interactions are necessary to allow the binding of core splicing factors prior to assembly of the spliceosomes on the two flanking introns.

The inclusion of tat exon 2 in the RNA is regulated by competition between the splicing repressor hnRNP A1 and the SR protein SC35.

External information is needed in order to decide which product is made, given a DNA sequence and the initial transcript.

Such functional diversity achieved by isoforms is reflected by their expression patterns and can be predicted by machine learning approaches.

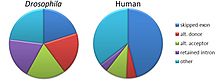

[38][39] However, a study on samples of 100,000 expressed sequence tags (EST) each from human, mouse, rat, cow, fly (D. melanogaster), worm (C. elegans), and the plant Arabidopsis thaliana found no large differences in frequency of alternatively spliced genes among humans and any of the other animals tested.

[44][45][46] Combined RNA-Seq and proteomics analyses have revealed striking differential expression of splice isoforms of key proteins in important cancer pathways.

[48][49] Transcriptome instability has further been shown to correlate grealty with reduced expression level of splicing factor genes.

Mutation of DNMT3A has been demonstrated to contribute to hematologic malignancies, and that DNMT3A-mutated cell lines exhibit transcriptome instability as compared to their isogenic wildtype counterparts.

[53] It is believed however that the deleterious effects of mis-spliced transcripts are usually safeguarded and eliminated by a cellular posttranscriptional quality control mechanism termed nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [NMD].

Three DNMT genes encode enzymes that add methyl groups to DNA, a modification that often has regulatory effects.

Production of an abnormally spliced transcript of Ron has been found to be associated with increased levels of the SF2/ASF in breast cancer cells.

[52] Overexpression of a truncated splice variant of the FOSB gene – ΔFosB – in a specific population of neurons in the nucleus accumbens has been identified as the causal mechanism involved in the induction and maintenance of an addiction to drugs and natural rewards.

[55][56][57][58] Recent provocative studies point to a key function of chromatin structure and histone modifications in alternative splicing regulation.

Transcriptome-wide analyses can for example be used to measure the amount of deviating alternative splicing, such as in a cancer cohort.

[60] Deep sequencing technologies have been used to conduct genome-wide analyses of both unprocessed and processed mRNAs; thus providing insights into alternative splicing.

High-throughput approaches to investigate splicing have, however, been developed, such as: DNA microarray-based analyses, RNA-binding assays, and deep sequencing.

[63] CLIP (Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation) uses UV radiation to link proteins to RNA molecules in a tissue during splicing.

[64] Recent advancements in protein structure prediction have facilitated the development of new tools for genome annotation and alternative splicing anlaysis.