Sponge

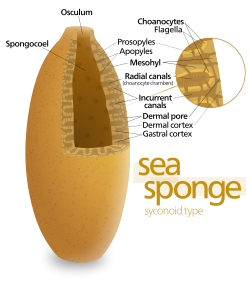

Sponges are multicellular organisms consisting of jelly-like mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of cells, and usually have tube-like bodies full of pores and channels that allow water to circulate through them.

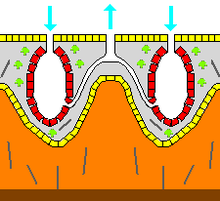

Instead, most rely on maintaining a constant water flow through their bodies to obtain food and oxygen and to remove wastes, usually via flagella movements of the so-called "collar cells".

Many sponges have internal skeletons of spicules (skeletal-like fragments of calcium carbonate or silicon dioxide), and/or spongin (a modified type of collagen protein).

[10] An internal gelatinous matrix called mesohyl functions as an endoskeleton, and it is the only skeleton in soft sponges that encrust such hard surfaces as rocks.

[13]: 120–127 The few species of demosponge that have entirely soft fibrous skeletons with no hard elements have been used by humans over thousands of years for several purposes, including as padding and as cleaning tools.

[16] Sponges constitute the phylum Porifera, and have been defined as sessile metazoans (multicelled immobile animals) that have water intake and outlet openings connected by chambers lined with choanocytes, cells with whip-like flagella.

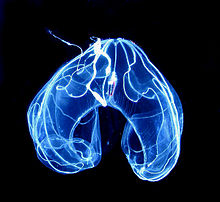

and ctenophores (comb jellies), and unlike all other known metazoans, sponges' bodies consist of a non-living jelly-like mass (mesohyl) sandwiched between two main layers of cells.

[20][21] Cnidarians and ctenophores have simple nervous systems, and their cell layers are bound by internal connections and by being mounted on a basement membrane (thin fibrous mat, also known as "basal lamina").

[18] Although the layers of pinacocytes and choanocytes resemble the epithelia of more complex animals, they are not bound tightly by cell-to-cell connections or a basal lamina (thin fibrous sheet underneath).

The flexibility of these layers and re-modeling of the mesohyl by lophocytes allow the animals to adjust their shapes throughout their lives to take maximum advantage of local water currents.

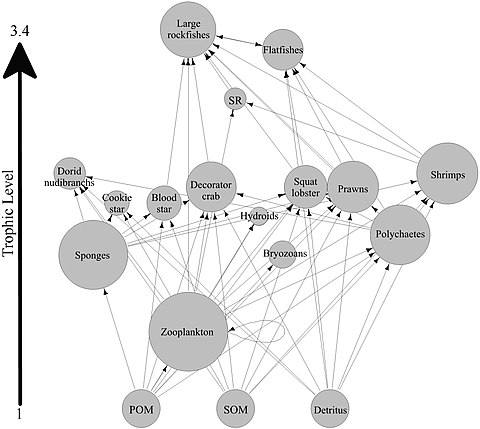

The "leuconoid" pattern boosts pumping capacity further by filling the interior almost completely with mesohyl that contains a network of chambers lined with choanocytes and connected to each other and to the water intakes and outlet by tubes.

For example, sclerosponges ("hard sponges") have massive calcium carbonate exoskeletons over which the organic matter forms a thin layer with choanocyte chambers in pits in the mineral.

[18] Although adult sponges are fundamentally sessile animals, some marine and freshwater species can move across the sea bed at speeds of 1–4 mm (0.039–0.157 in) per day, as a result of amoeba-like movements of pinacocytes and other cells.

[31] Collar bodies digest food and distribute it wrapped in vesicles that are transported by dynein "motor" molecules along bundles of microtubules that run throughout the syncytium.

Archeocytes remove mineral particles that threaten to block the ostia, transport them through the mesohyl and generally dump them into the outgoing water current, although some species incorporate them into their skeletons.

[34][35] Most carnivorous sponges live in deep waters, up to 8,840 m (5.49 mi),[36] and the development of deep-ocean exploration techniques is expected to lead to the discovery of several more.

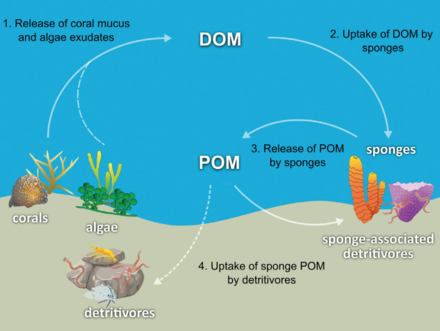

[38] Sponges that host photosynthesizing organisms are most common in waters with relatively poor supplies of food particles and often have leafy shapes that maximize the amount of sunlight they collect.

When invaded, they produce a chemical that stops movement of other cells in the affected area, thus preventing the intruder from using the sponge's internal transport systems.

They use the mobility of their pinacocytes and choanocytes and reshaping of the mesohyl to re-attach themselves to a suitable surface and then rebuild themselves as small but functional sponges over the course of several days.

[18]: 77 [42] Glass sponge embryos start by dividing into separate cells, but once 32 cells have formed they rapidly transform into larvae that externally are ovoid with a band of cilia round the middle that they use for movement, but internally have the typical glass sponge structure of spicules with a cobweb-like main syncitium draped around and between them and choanosyncytia with multiple collar bodies in the center.

[44] Since porifera are considered to be the earliest divergent animals, these findings indicate that the basic toolkit of meiosis including capabilities for recombination and DNA repair were present early in eukaryote evolution.

However, most species have the ability to perform movements that are coordinated all over their bodies, mainly contractions of the pinacocytes, squeezing the water channels and thus expelling excess sediment and other substances that may cause blockages.

[45] However, glass sponges rapidly transmit electrical impulses through all parts of the syncytium, and use this to halt the motion of their flagella if the incoming water contains toxins or excessive sediment.

[29] They also produce toxins that prevent other sessile organisms such as bryozoans or sea squirts from growing on or near them, making sponges very effective competitors for living space.

[79][further explanation needed] For a long time thereafter, sponges were assigned to subkingdom Parazoa ("beside the animals") separated from the Eumetazoa which formed the rest of the kingdom Animalia.

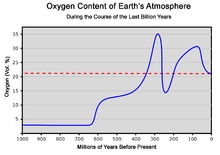

[97] Fossils found in the Canadian Northwest Territories dating to 890 million years ago may be sponges; if this finding is confirmed, it suggests the first animals appeared before the Neoproterozoic oxygenation event.

An analysis in 1996 concluded that they were closely related to sponges on the grounds that the detailed structure of chancellorid sclerites ("armor plates") is similar to that of fibers of spongin, a collagen protein, in modern keratose (horny) demosponges such as Darwinella.

If this is correct, it would create a dilemma, as it is extremely unlikely that totally unrelated organisms could have developed such similar sclerites independently, but the huge difference in the structures of their bodies makes it hard to see how they could be closely related.

[113] However, reanalysis of the data showed that the computer algorithms used for analysis were misled by the presence of specific ctenophore genes that were markedly different from those of other species, leaving sponges as either the sister group to all other animals, or an ancestral paraphyletic grade.

[13]: 88 Early Europeans used soft sponges for many purposes, including padding for helmets, portable drinking utensils and municipal water filters.

-

Mesohyl

-

Spicules

-

Seabed / rock

-

Water flow