Step response

From a practical standpoint, knowing how the system responds to a sudden input is important because large and possibly fast deviations from the long term steady state may have extreme effects on the component itself and on other portions of the overall system dependent on this component.

This section describes the step response of a simple negative feedback amplifier shown in Figure 1.

This forward amplifier has unit step response an exponential approach from 0 toward the new equilibrium value of A0.

In the case that the open-loop gain has two poles (two time constants, τ1, τ2), the step response is a bit more complicated.

The two-pole amplifier's transfer function leads to the closed-loop gain: The time dependence of the amplifier is easy to discover by switching variables to s = jω, whereupon the gain becomes: The poles of this expression (that is, the zeros of the denominator) occur at: which shows for large enough values of βA0 the square root becomes the square root of a negative number, that is the square root becomes imaginary, and the pole positions are complex conjugate numbers, either s+ or s−; see Figure 2: with and Using polar coordinates with the magnitude of the radius to the roots given by |s| (Figure 2): and the angular coordinate φ is given by: Tables of Laplace transforms show that the time response of such a system is composed of combinations of the two functions: which is to say, the solutions are damped oscillations in time.

In particular, the unit step response of the system is:[2] which simplifies to when A0 tends to infinity and the feedback factor β is one.

Figure 3 shows the time response to a unit step input for three values of the parameter μ.

These asymptotes are determined by ρ and therefore by the time constants of the open-loop amplifier, independent of feedback.

The two major conclusions from this analysis are: As an aside, it may be noted that real-world departures from this linear two-pole model occur due to two major complications: first, real amplifiers have more than two poles, as well as zeros; and second, real amplifiers are nonlinear, so their step response changes with signal amplitude.

Using the equations above, the amount of overshoot can be found by differentiating the step response and finding its maximum value.

The case α = 2 (center panel) is the maximally flat design that shows no peaking in the Bode gain vs. frequency plot.

That design has the rule of thumb built-in safety margin to deal with non-ideal realities like multiple poles (or zeros), nonlinearity (signal amplitude dependence) and manufacturing variations, any of which can lead to too much overshoot.

The amplitude of ringing in the step response in Figure 3 is governed by the damping factor exp(−ρt).

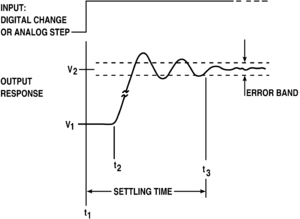

That is, if we specify some acceptable step response deviation from final value, say Δ, that is: this condition is satisfied regardless of the value of β AOL provided the time is longer than the settling time, say tS, given by:[4] where the τ1 ≫ τ2 is applicable because of the overshoot control condition, which makes τ1 = αβAOL τ2.

[8] Here the steps: Next, the choice of pole ratio τ1/τ2 is related to the phase margin of the feedback amplifier.

Figure 5 is the Bode gain plot for the two-pole amplifier in the range of frequencies up to the second pole position.