Supercontinent

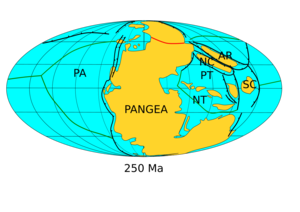

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass.

[1][2][3] However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leaves room for interpretation and is easier to apply to Precambrian times.

[5] Moving under the forces of plate tectonics, supercontinents have assembled and dispersed multiple times in the geologic past.

According to modern definitions, a supercontinent does not exist today;[1] the closest is the current Afro-Eurasian landmass, which covers approximately 57% of Earth's total land area.

[6] Pangaea's predecessor Gondwana is not considered a supercontinent under the first definition since the landmasses of Baltica, Laurentia and Siberia were separate at the time.

Contributing to Pangaea's popularity in the classroom, its reconstruction is almost as simple as fitting together the present continents bordering the Atlantic ocean like puzzle pieces.

These parts of Neoarchean age broke off at ~2480 and 2312 Ma, and portions of them later collided to form Nuna (Northern Europe and North America).

[4] The following table names reconstructed ancient supercontinents, using Bradley's 2011 looser definition,[7] with an approximate timescale of millions of years ago (Ma).

The causes of supercontinent assembly and dispersal are thought to be driven by convection processes in Earth's mantle.

Approximately 660 km into the mantle, a discontinuity occurs, affecting the surface crust through processes involving plumes and superplumes (aka large low-shear-velocity provinces).

[1] Besides having compositional effects on the upper mantle by replenishing the large-ion lithophile elements, volcanism affects plate movement.

[18] Accretion occurs over geoidal lows that can be caused by avalanche slabs or the downgoing limbs of convection cells.

However, due to a lack of data on the time required to produce flood basalts, the climatic impact is difficult to quantify.

Marine magnetic anomalies, passive margin match-ups, geologic interpretation of orogenic belts, paleomagnetism, paleobiogeography of fossils, and distribution of climatically sensitive strata are all methods to obtain evidence for continent locality and indicators of the environment throughout time.

The orogenic belts present on continental blocks are classified into three different categories and have implications for interpreting geologic bodies.

Clear indicators of intracratonic activity contain ophiolites and other oceanic materials that are present in the suture zone.

[19] According to the model for Precambrian supercontinent series, the breakup of Kenorland and Rodinia was associated with the Paleoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic glacial epochs, respectively.

In contrast, the Protopangea–Paleopangea theory shows that these glaciations correlated with periods of low continental velocity, and it is concluded that a fall in tectonic and corresponding volcanic activity was responsible for these intervals of global frigidity.

[11] During the accumulation of supercontinents with times of regional uplift, glacial epochs seem to be rare with little supporting evidence.

During the late Ordovician (~458.4 Ma), the particular configuration of Gondwana may have allowed for glaciation and high CO2 levels to occur at the same time.

This increase may have been strongly influenced by the movement of Gondwana across the South Pole, which may have prevented lengthy snow accumulation.

[20] Though precipitation rates during monsoonal circulations are difficult to predict, there is evidence for a large orographic barrier within the interior of Pangaea during the late Paleozoic (~251.9 Ma).

This may be due to high seafloor spreading rates after the breakup of Precambrian supercontinents and the lack of land plants as a carbon sink.

Present amplitudes of Milankovitch cycles over present-day Eurasia may be mirrored in both the southern and northern hemispheres of the supercontinent Pangaea.

[22] Plate tectonics and the chemical composition of the atmosphere (specifically greenhouse gases) are the two most prevailing factors present within the geologic time scale.

These super-mountains would have eroded, and the mass amounts of nutrients, including iron and phosphorus, would have washed into oceans, just as is seen happening today.

Evidence supporting this event includes red beds appearance 2.3 Ga (meaning that Fe3+ was being produced and became an important component in soils).

The fourth oxygenation event, roughly 0.6 Ga, is based on modeled rates of sulfur isotopes from marine carbonate-associated sulfates.

The sixth event occurred between 360 and 260 Ma and was identified by models suggesting shifts in the balance of 34S in sulfates and 13C in carbonates, which were strongly influenced by an increase in atmospheric oxygen.

[4] Oceanic magnetic anomalies and paleomagnetic data are the primary resources used for reconstructing continent and supercontinent locations back to roughly 150 Ma.