Sushruta Samhita

The Compendium of Suśruta is one of the foundational texts of Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine), alongside the Charaka-Saṃhitā, the Bhela-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.

The most detailed and extensive consideration of the date of the Suśrutasaṃhitā is that published by Meulenbeld in his History of Indian Medical Literature (1999-2002).

In Suśrutasaṃhitā - A Scientific Synopsis, the historians of Indian science Ray, Gupta and Roy noted the following view, which is broadly the same as Meulenbeld's:[8]"The Chronology Committee of the National Institute of Sciences of India (Proceedings, 1952),[9] was of the opinion that third to fourth centuries A. D. may be accepted as the date of the recension of the Suśruta Saṃhitā by Nāgārjuna, which formed the basis of Dallaṇa's commentary.

[10] However, Hoernle's view was based on the unexamined assumption that the ideas about the human skeleton in the Suśrutasaṃhitā preceded those of the Brāhmaṇa.

The internal tradition recorded in manuscript colophons and by medieval commentators makes clear that an old version of the Suśrutasaṃhitā consisted of sections 1-5, with the sixth part having been added by a later author.

As mentioned above, scores of scholars have proposed hypotheses on the formation and dating of the Suśrutasaṃhitā, ranging from 2000 BCE to the sixth century CE.

'well heard',[13] an adjective meaning "renowned"[14]) is named in the text as the author, who is presented in later manuscripts and printed editions a narrating the teaching of his guru, Divodāsa.

[15][16] Early Buddhist Jatakas mention a Divodāsa as a physician who lived and taught in ancient Kashi (Varanasi).

[19][20][21] The text discusses surgery with the same terminology found in more ancient Hindu texts,[22][23] mentions Hindu gods such as Narayana, Hari, Brahma, Rudra, Indra and others in its chapters,[24][25] refers to the scriptures of Hinduism namely the Vedas,[26][27] and in some cases, recommends exercise, walking and "constant study of the Vedas" as part of the patient's treatment and recovery process.

The text may have Buddhist influences, since a redactor named Nagarjuna has raised many historical questions, although he cannot have been the person of Mahayana Buddhism fame.

[32] Zysk produced evidence that the medications and therapies mentioned in the Pāli Canon bear strong resemblances and are sometimes identical to those of the Suśrutasaṃhitā and the Carakasaṃhitā.

[33] In general, states Zysk, Buddhist medical texts are closer to Sushruta than to Caraka,[34] and in his study suggests that the Sushruta Samhita probably underwent a "Hinduization process" around the end of 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of the common era after the Hindu orthodox identity had formed.

[36] The mutual influence between the medical traditions between the various Indian religions, the history of the layers of the Suśruta-saṃhitā remains unclear, a large and difficult research problem.

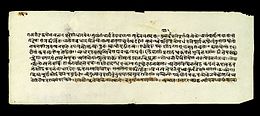

A microfilm copy of the MS was created by Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project (NGMCP C 80/7) and is stored in the National Archives, Kathmandu.

[6] The partially damaged manuscript consists of 152 folios, written on both sides, with 6 to 8 lines in transitional Gupta script.

Hence, any one desirous of acquiring a thorough knowledge of anatomy should prepare a dead body and carefully, observe, by dissecting it, and examine its different parts.

[124] The text then lists the total of 300 as follows: 120 in the extremities (e.g. hands, legs), 117 in the pelvic area, sides, back, abdomen and breast, and 63 in the neck and upwards.

[125] The osteological system of Sushruta, states Hoernle, follows the principle of homology, where the body and organs are viewed as self-mirroring and corresponding across various axes of symmetry.

[130] Incision studies, for example, are recommended on Pushpaphala (squash, Cucurbita maxima), Alabu (bottle gourd, Lagenaria vulgaris), Trapusha (cucumber, Cucumis pubescens), leather bags filled with fluids and bladders of dead animals.

[131] The ancient text, state Menon and Haberman, describes haemorrhoidectomy, amputations, plastic, rhinoplastic, ophthalmic, lithotomic and obstetrical procedures.

[135] The descriptions include the herbs' taste, appearance, digestive effects, safety, efficacy, dosage, and benefits.

Rhinoplasty was an especially important development in India because of the long-standing tradition of rhinotomy (amputation of the nose) as a form of punishment.

[141][142] There is disputed evidence that in Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily[141] and Gasparo Tagliacozzi (Bologna) were familiar with the rhinoplastic techniques mentioned in the Sushruta Samhita.

The first complete English translation of the Sushruta Samhita was by Kaviraj Kunjalal Bhishagratna, who published it in three volumes between 1907 and 1916 (reprinted 1963, 2006).

[151][note 1] An English translation of both the Sushruta Samhita and Dalhana's commentary was published in three volumes by P. V. Sharma in 1999.