Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War

Peace of Prague Swedish Empire Saxony (from 1631)[a] Heilbronn League (from 1633) Hesse-Kassel Brandenburg-Prussia Catholic League and allies: Habsburg Monarchy Gustav II Adolf † Axel Oxenstierna Johan Banér Lennart Torstenson Gustav Horn Bernard of Saxe-Weimar Alexander Leslie John George I George William Albrecht von Wallenstein † Count Tilly † Ferdinand II Ferdinand III Gottfried Pappenheim † Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand Count Leganés 1630: 70,600 13,000 men landing in Germany[1][2] 24,600 men garrisoning Sweden 33,000 German allies and mercenaries 1632: 140,000[3] 25,000 Swedes and Finns in Germany The Swedish invasion of the Holy Roman Empire or the Swedish Intervention in the Thirty Years' War is a historically accepted division of the Thirty Years' War.

Following the Edict of Restitution by Emperor Ferdinand II on the height of his and the Catholic League's military success in 1629, Protestantism in the Holy Roman Empire was seriously threatened.

It established the legitimacy of Lutheranism[5] in Germany and allowed Dukes and high lords to determine the faith of their fiefdom as well as to expel non-conforming subjects from their territory, the principle known as Cuius regio, eius religio.

Although genuine ideological differences did drive German Princes to convert, the primary motivation of many was often the acquisition of easy riches and territory at the expense of their defenceless Catholic neighbours and subjects.

The noblemen held a trial on the spot, found the Imperial officials guilty of violating the Letter of Majesty, and threw them out of a third-floor window of the Bohemian Chancellery.

However the act of unseating Ferdinand – the legitimately chosen monarch of Bohemia[6]- put the Bohemian revolt in a difficult position with the other political powers of Germany and Europe.

[15] According to one historian, luxury was a "...stranger in the camp..."[16] All soldiers who were caught looting were to be court-marshalled and then shot,[17] nepotism and other forms of favoritism[18] were unknown[17] in the Swedish army.

[18] The purpose of this organ was to give more rigid structure to the already existing social order, and aid in effective representation of the respective bodies; those being nobles, clergy, burghers and peasants.

The king, perceiving the advantages that Sigismund would thus gain, in June[31] sailed with a fleet to Danzig and compelled the city to pledge itself to neutrality in the conflict between Poland and Sweden.

[31] During this peace, which was to last until 1625,[31] the king worked further in reforming Sweden's military establishment, among which a regular army of 80,000 was settled upon, in addition to an equally great force for the National Guard.

So many personal motives, supported by important considerations, both of policy and religion, and seconded by pressing invitations from Germany, had their full weight with a prince, who was naturally the more jealous of his royal prerogative the more it was questioned, who was flattered by the glory he hoped to gain as Protector of the oppressed, and passionately loved war as the element of his genius.

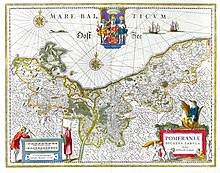

Gustavus believed that it was absolutely essential that he should hold the entirety of the Baltic coast, because he would be no good in Germany if the Catholic powers could operate on his lines of communication and threaten his throne.

[53] The king proposed that he should land his armada at the Oder delta and treat with each of the cities in the vicinity to gain firm grip on the country before making any inroads into the interior of Germany.

[54] Feeling confident that he had secured his landing, by the end of the month, the king sent to Oxenstierna a small portion of his fleet to gather supplies and bring them to his position at the delta of the Oder.

[56] So bad were the conditions prevailing in Germany at the time, many other men voluntarily enlisted into the Swedish ranks – it was easier for a villager to get food within an army then if he were living in the countryside.

[67] However, despite the unprecedented victories that Wallenstien had brought him, and his virtually unassailable position, he was politically vulnerable and needed to appease the German princes pressing him for Wallenstein's dismissal.

[68] The Catholic and Protestant princes (and specifically electors) were unanimous in their outrage and exacerbation with Wallenstein and his mercenary army, and were in a position to leverage the Emperor's action in a material way.

[73] These were stationed there so that he could retreat towards them if a numerically larger foe should present itself against his front at Soldin,[73] while simultaneously protecting Swedish gains along the right bank of the Oder and Eastern Pomerania.

Inversely, if he stayed here to protect the Warta line (which if opened would give the Swedes free access into the hereditary lands of the Austrian emperors), then the Swedish would have an easy time of marching into Mecklenburg over the Havel and relieving the siege at Magdeburg.

Although the king was seriously considering wintering his troops at the present, he himself, as well as Knyphausen, came to believe that Tilly was contemplating a march on Neuruppin in an attempt to relieve the siege that was taking place at Greifswald.

In addition to his sister being the Queen of Sweden, George William was the vassal of Gustavus' cousin and most inveterate foe, Sigismund III Vasa, in his capacity as duke of the Duchy of Prussia.

As Protestant Germany had been more outraged then cowed by the sack of Magdeburg, in reality these forces were being raised to defend themselves against clear Imperial aggression and maintain their rights as independent princes of their principalities.

Despite the strategic drawback and moral consequences that the Swedes faced with the fall Magdeburg, they had increased their grip on Germany and had achieved one of their primary objectives, securing the southern Baltic coast.

[101] While on their march from Italy, the reinforcements compelled the princelings to submit to the emperor, using the threat of major fines to force them to enlist their troops in the service of the Imperial cause.

[101] The recently defeated Tilly, fearing the intervention of Swedish reinforcements from the right (eastern) bank of the Elbe, had placed himself at Wolmirstedt[101] to be close to Hesse–Kassel, Saxony, and Brandenburg.

Trenches were opened by the Imperials,[105] heavy guns were placed at Pfaffendorf (immediately in the environs of Leipzig) and entrenched a number of heights that had commanding positions on roads approaching the city, in order to exclude relieving forces from the area.

[113] The small companies of musketeers dispersed between the squadrons of horse fired a salvo at point blank range, disrupting the charge of the Imperialist cuirassier and allowing the Swedish cavalry to counterattack at an advantage.

[126] In pursuit of this general scheme, Baner[127] was ordered to leave a garrison in Landsburg, to surrender Frankfort and Crossen to the elector of Brandenburg[127] and to assume command of the Saxon units when they should be in a suitable condition to fight – which their recent precipitous retreat from Breitenfeld revealed to be greatly wanting.

In a pitched battle, the Swedish army defeated Wallenstein's forces, but King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, the 'father of modern warfare', was killed during a confused cavalry charge which he had personally led.

[148] The Swedish Army under Gustavus Adolphus' successors Gustav Horn and Bernard of Saxe-Weimar would return to Bavaria and capture Regensburg the following year in 1633, only to lose it again to Imperial forces in 1634.

Habsburg-controlled domains:

Austrian line

Spanish line

Counter march not depicted.

English reinforcements in yellow

Swedish-Saxon forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red

Swedish forces in Blue

Catholic army in Red