Synchronous motor

A synchronous electric motor is an AC electric motor in which, at steady state,[1] the rotation of the shaft is synchronized with the frequency of the supply current; the rotation period is exactly equal to an integer number of AC cycles.

Doubly fed synchronous motors use independently-excited multiphase AC electromagnets for both rotor and stator.

Synchronous motors rotate at a rate locked to the line frequency since they do not rely on induction to produce the rotor's magnetic field.

Small synchronous motors are used in timing applications such as in synchronous clocks, timers in appliances, tape recorders and precision servomechanisms in which the motor must operate at a precise speed; accuracy depends on the power line frequency, which is carefully controlled in large interconnected grid systems.

In typical industrial sizes, the synchronous motor provides an efficient means of converting AC energy to work (electrical efficiency above 95% is normal for larger sizes)[4] and it can operate at leading or unity power factor and thereby provide power-factor correction.

Generator action occurs if the field poles are "driven ahead of the resultant air-gap flux by the forward motion of the prime mover".

Motor action occurs if the field poles are "dragged behind the resultant air-gap flux by the retarding torque of a shaft load".

[1] The two major types of synchronous motors are distinguished by how the rotor is magnetized: non-excited and direct-current excited.

The stator carries windings connected to an AC electricity supply to produce a rotating magnetic field (as in an asynchronous motor).

[15] These are typically used as higher-efficiency replacements for induction motors (owing to the lack of slip), but must ensure that synchronous speed is reached and that the system can withstand torque ripple during starting.

[17] Reluctance motors have a solid steel cast rotor with projecting (salient) toothed poles.

This creates torque that pulls the rotor into alignment with the nearest pole of the stator field.

This cannot start the motor, so the rotor poles usually have squirrel-cage windings embedded in them, to provide torque below synchronous speed.

The machine thus starts as an induction motor until it approaches synchronous speed, when the rotor "pulls in" and locks to the stator field.

[19] Reluctance motor designs have ratings that range from fractional horsepower (a few watts) to about 22 kW.

When used with an adjustable frequency power supply, all motors in a drive system can operate at exactly the same speed.

Hysteresis motors have a solid, smooth, cylindrical rotor, cast of a high coercivity magnetically "hard" cobalt steel.

More expensive than the reluctance type, hysteresis motors are used where precise constant speed is required.

There is a large number of control methods for synchronous machines, selected depending on the construction of the electric motor and the scope.

[28] The stator frame contains wrapper plate (except for wound-rotor synchronous doubly fed electric machines).

Electric motors generate power due to the interaction of the magnetic fields of the stator and the rotor.

Because this winding is smaller than that of an equivalent induction motor and can overheat on long operation, and because large slip-frequency voltages are induced in the rotor excitation winding, synchronous motor protection devices sense this condition and interrupt the power supply (out of step protection).

This property is due to rotor inertia; it cannot instantly follow the rotation of the stator's magnetic field.

[35][36] Electronically controlled motors can be accelerated from zero speed by changing the frequency of the stator current.

[3] Single-phase synchronous motors such as in electric wall clocks can freely rotate in either direction, unlike a shaded-pole type.

[39] In addition, starting methods for large synchronous machines include repetitive polarity inversion of the rotor poles during startup.

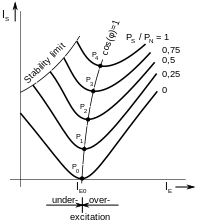

[40] By varying the excitation of a synchronous motor, it can be made to operate at lagging, leading and unity power factor.