Taensa

[11][12][13][14][9] The post-Hernando de Soto entrada Transylvania Phase (1550-1700 CE) of the Tensas Basin saw the increasing spread of Mississippian influences diffusing southward from Arkansas and northwestern Mississippi.

[15] The Jordan Mounds site on a relict channel of the Arkansas River in northeastern Louisianas Morehouse Parish was constructed during the protohistoric period between 1540 and 1685.

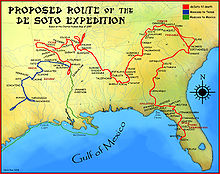

[16] Historians and archaeologists such as Marvin Jeter have theorized that the Plaquemine "Northern Natchezan" ancestors of the Taensa were in part some of the peoples documented in the early 1540s by the de Soto expedition in southeastern Arkansas and northwestern Mississippi.

They numbered approximately 1,200 people scattered throughout seven or eight villages on the western end of the lake and another on the Tensas River near present-day Clayton in Concordia Parish.

La Source (a lay person and possible servant to the priests) visited the Taensa;[23] de Montigny founded a short-lived mission among them.

[24][4] During his time with the Taensa, de Montigny prevented them from performing acts of ritual human sacrifice as part of the funeral rites for a deceased chief.

Along with other native peoples of the lower Mississippi River, the Taensa were subject to slave raids and epidemics of European diseases such as smallpox during this time period.

As the population of the Taensa steadily decreased, de Saint-Cosme in 1700 endeavored in vain to have them join with the much larger Natchez and consolidate the two missions.

[4][25][26][27] During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, French colonists in the American Southeast initiated a power struggle with those living in the colony of Carolina.

Traders from Carolina had established a large trading network among the indigenous peoples of the American Southeast, and by 1700 it stretched west as far as the Mississippi River.

The Chickasaw tribe, who lived north of the Taensa, were frequently visited by Carolinian traders, thus giving them access to a source of firearms and alcohol.

For decades, the Chickasaw conducted slave raids over a wide region in the American Southeast, often being joined by allied Natchez and Yazoo warriors.

[28] In 1706, fearing a slaver raid by a combined force of Chickasaw and Yazoo raiders, the Taensa abandoned their village on Lake St. Joseph.

Conflicts soon developed, and the Taensa attacked and nearly exterminated the Bayogoula peoples and burned their village down—an act described as treacherous by later historians.

"[2] The Taensa were a Natchezan people who separated from the main body of the Natchez sometime prior to European contact with the Lower Mississippi Valley region.

[24] Chiefs exercised absolute power and were treated with great respect; unlike more egalitarian customs among the northern tribes the early chroniclers were used to.

[2] The beginning of the Transylvania Phase (1550-1700 CE) of the Tensas Basin region saw the increasing spread of Mississippian influences diffusing southward from what is now southeastern Arkansas.

[34] The Taensa were sedentary maize growing agriculturalists as opposed to hunter gatherers and lived in permanent villages with wattle and daub buildings.

Like other Native Americans in the southeast it also had an open plaza area used for public rituals and functions such as the Green Corn Ceremony and games such as chunkey and the ballgame.

[36][37] This pattern of plazas flanked by mounds with temples, elite residences and mortuary structures at their summits was inherited from their Plaquemine and Coles Creek ancestors, and was a village arrangement widely employed throughout the southeast.

The chief sat on one that acted as a throne where he would hold court surrounded by his wives, retainers, and advisers who were all dressed in white garments woven from mulberry bark.

Inside were interred the bones of their chiefs and other honored dead, human and animal forms carved in stone, wood, and modeled as ceramic figurines, stuffed owls, jawbones of large fish, "heads and tails of extraordinary serpents", pieces of quartz crystal, and some European glass objects.

[40][41] Taensa religious life revolved around the worship of the sun, represented by the sacred fire kept perpetually burning inside their temple.

[45] Upon the death of high-ranking individuals, the Taensa practiced ritual human sacrifice of retainers to accompany them as servants in the afterlife.

An early chronicler, Henri de Tonti, wrote that when their Great Chief died, "They sacrifice his youngest wife, his house steward, and a hundred men to accompany him in the other world."

[49] Between 1880 and 1882, a young clerical student in Paris named Jean Parisot published what was purported to be "material of the Taensa language, including papers, songs, a grammar and vocabulary"; this generated considerable interest among philologists.

There was doubt about this material for many years; noted American anthropologist and linguist John R. Swanton conclusively proved the work to be a hoax in a series of publications in 1908-1910.