Sufism

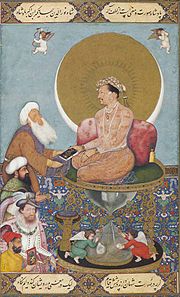

ṭuruq) — congregations formed around a grand wali (saint) who would be the last in a chain of successive teachers linking back to Muhammad, with the goal of undergoing tazkiya (self purification) and the hope of reaching the spiritual station of ihsan.

[15] The term Sufism was originally introduced into European languages in the 18th century by Orientalist scholars, who viewed it mainly as an intellectual doctrine and literary tradition at variance with what they saw as sterile monotheism of Islam.

"[30][31] Others have suggested that the word comes from the term Ahl al-Ṣuffa[32] ("the people of the suffah" or the bench), who were a group of impoverished companions of Muhammad who held regular gatherings of dhikr.

[42] Historian Jonathan A.C. Brown notes that during the lifetime of Muhammad, some companions were more inclined than others to "intensive devotion, pious abstemiousness and pondering the divine mysteries" more than Islam required, such as Abu Dharr al-Ghifari.

[67] Existing in both Sunni and Shia Islam, Sufism is not a distinct sect, as is sometimes erroneously assumed, but a method of approaching or a way of understanding the religion, which strives to take the regular practice of the religion to the "supererogatory level" through simultaneously "fulfilling ... [the obligatory] religious duties"[2] and finding a "way and a means of striking a root through the 'narrow gate' in the depth of the soul out into the domain of the pure arid un-imprisonable Spirit which itself opens out on to the Divinity.

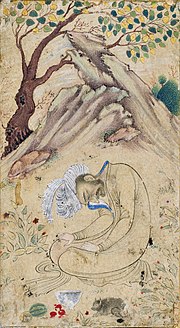

By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.

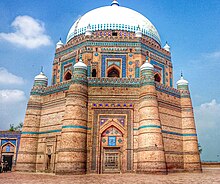

All these orders were founded by a major Islamic scholar, and some of the largest and most widespread included the Suhrawardiyya (after Abu al-Najib Suhrawardi [d. 1168]), Qadiriyya (after Abdul-Qadir Gilani [d. 1166]), the Rifa'iyya (after Ahmed al-Rifa'i [d. 1182]), the Chishtiyya (after Moinuddin Chishti [d. 1236]), the Shadiliyya (after Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili [d. 1258]), the Hamadaniyyah (after Sayyid Ali Hamadani [d. 1384]), the Naqshbandiyya (after Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari [d.

[87] Around the turn of the 20th century, Sufi rituals and doctrines also came under sustained criticism from modernist Islamic reformers, liberal nationalists, and, some decades later, socialist movements in the Muslim world.

Ideological attacks on Sufism were reinforced by agrarian and educational reforms, as well as new forms of taxation, which were instituted by Westernizing national governments, undermining the economic foundations of Sufi orders.

Its ability to articulate an inclusive Islamic identity with greater emphasis on personal and small-group piety has made Sufism especially well-suited for contexts characterized by religious pluralism and secularist perspectives.

[87] In the modern world, the classical interpretation of Sunni orthodoxy, which sees in Sufism an essential dimension of Islam alongside the disciplines of jurisprudence and theology, is represented by institutions such as Egypt's Al-Azhar University and Zaytuna College, with Al-Azhar's current Grand Imam Ahmed el-Tayeb recently defining "Sunni orthodoxy" as being a follower "of any of the four schools of [legal] thought (Hanafi, Shafi’i, Maliki or Hanbali) and ... [also] of the Sufism of Imam Junayd of Baghdad in doctrines, manners and [spiritual] purification.

[100] Although approaches to teaching vary among different Sufi orders, Sufism as a whole is primarily concerned with direct personal experience, and as such has sometimes been compared to other, non-Islamic forms of mysticism (e.g., as in the books of Seyyed Hossein Nasr).

Many Sufi believe that to reach the highest levels of success in Sufism typically requires that the disciple live with and serve the teacher for a long period of time.

[112] Sufism leads the adept, called salik or "wayfarer", in his sulûk or "road" through different stations (maqāmāt) until he reaches his goal, the perfect tawhid, the existential confession that God is One.

[129] While variation exists, one description of the practice within a Naqshbandi lineage reads as follows: He is to collect all of his bodily senses in concentration, and to cut himself off from all preoccupation and notions that inflict themselves upon the heart.

Since the first Muslim hagiographies were written during the period when Sufism began its rapid expansion, many of the figures who later came to be regarded as the major saints in Sunni Islam were the early Sufi mystics, like Hasan of Basra (d. 728), Farqad Sabakhi (d. 729), Dawud Tai (d. 777-81) Rabi'a al-'Adawiyya (d. 801), Maruf Karkhi (d. 815), and Junayd of Baghdad (d. 910).

This is a particularly common practice in South Asia, where famous tombs include such saints as Sayyid Ali Hamadani in Kulob, Tajikistan; Afāq Khoja, near Kashgar, China; Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sindh; Ali Hujwari in Lahore, Pakistan; Bahauddin Zakariya in Multan Pakistan; Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, India; Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi, India; and Shah Jalal in Sylhet, Bangladesh.

In the technical vocabulary of Islamic religious sciences, the singular form karama has a sense similar to charism, a favor or spiritual gift freely bestowed by God.

He taught that his followers need not abstain from what Islam has not forbidden, but to be grateful for what God has bestowed upon them,[178] in contrast to the majority of Sufis, who preach to deny oneself and to destroy the ego-self (nafs).

Ibn Arabi's writings, especially al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya and Fusus al-Hikam, have been studied within all Sufi orders as the clearest expression of tawhid (Divine Unity), though because of their recondite nature they were often only given to initiates.

[239] The contemporary amateur historian David Livingstone writes: "Sufi practices are merely attempts to attain psychic states—for their own sake—though it is claimed the pursuit represents seeking closeness to God, and that the achieved magical powers are gifts of advanced spirituality.

Also, many of the Sufis adopted the practice of total Tawakkul, or complete "trust" or "dependence" on God, by avoiding all kinds of labor or commerce, refusing medical care when they were ill, and living by begging.

[241] According to Philip Jenkins, a professor at Baylor University, "the Sufis are much more than tactical allies for the West: they are, potentially, the greatest hope for pluralism and democracy within Muslim nations."

", and that Ibn al-Farid "stresses that Sufism lies behind and before systematization; that 'our wine existed before what you call the grape and the vine' (the school and the system)..."[249] Shah's views have however been rejected by modern scholars.

The tenth-century Persian polymath Al-Biruni in his book Tahaqeeq Ma Lilhind Min Makulat Makulat Fi Aliaqbal Am Marzula (Critical Study of Indian Speech: Rationally Acceptable or Rejected) discusses the similarity of some Sufism concepts with aspects of Hinduism, such as: Atma with ruh, tanasukh with reincarnation, Mokhsha with Fanafillah, Ittihad with Nirvana: union between Paramatma in Jivatma, Avatar or Incarnation with Hulul, Vedanta with Wahdatul Ujud, Mujahadah with Sadhana.

[citation needed] Other scholars have likewise compared the Sufi concept of Waḥdat al-Wujūd to Advaita Vedanta,[251] Fanaa to Samadhi,[252] Muraqaba to Dhyana, and tariqa to the Noble Eightfold Path.

[253] The ninth-century Iranian mystic Bayazid Bostami is alleged to have imported certain concepts from Hindusim into his version of Sufism under the conceptual umbrella of baqaa, meaning perfection.

[263] Abraham Maimonides' principal work was originally composed in Judeo-Arabic and entitled "כתאב כפאיה אלעאבדין" Kitāb Kifāyah al-'Ābidīn (A Comprehensive Guide for the Servants of God).

[271] Spiritual experiences were desired by Sufis through Sama, listening to poetry or Islamic mystical verses with the use of different musical instruments, aiming to attain ecstasy in divine love of Allah and his Prophet.

Abdul Basit who was the High Commissioner of Pakistan to India at that time, while inaugurating the exhibition of Farkhananda Khan ‘Fida’ said, "There is no barrier of words or explanation about the paintings or rather there is a soothing message of brotherhood, peace in Sufism".