Augusta Treverorum

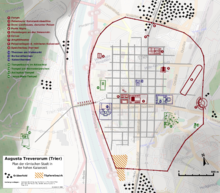

In the Roman Empire, Trier formed the main town of the civitas of the Treverians, where several ten thousand people lived, and belonged to the province of Gallia Belgica.

Between the confluence of the Saar and the entrance to the entrenched meanders of the Middle and Lower Moselle, the Trier valley width between Konz and Schweich is the largest settlement chamber in the region.

[1] The deeply incised stream courses of Olewiger Bach/Altbach, Aulbach and Aveler Bach provided both fresh water and easy access to the surrounding heights.

An evaluation of the early Roman finds from the city area has shown that a large-scale settlement cannot be expected before the late Augustan period (Haltern horizon).

Due to its location in the hinterland, Trier was spared for a long time from the Germanic invasions during the so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century, which led to the abandonment of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes (Limesfall).

In order to consolidate his claim to power – which contradicted the actual rule of succession to the throne – in propaganda terms, Constantine had a monumental palace complex built (even by late antique standards) on the model of the Palatine in Rome.

The succession of finishing phases, first in timber-framed construction, from the late 1st century limestone and finally red sandstone, can be observed on many private buildings, including a residential complex uncovered near St. Irminen in 1976/1977.

Foundations of such buildings could be proved archaeologically at the city-side bridgehead of the Moselle bridge, between Simeon- and Moselle-street as well as a blocked rest in an arch of the imperial thermae.

On Langstraße, a part is accessible along the length of 70 m.[55] The city wall had a total of five gate buildings, some of which, like the Porta Nigra, were very elaborately designed and at the time of their construction already anticipated the later widespread type of fortified gateaway.

It owes its preservation to the fact that in the Middle Ages Simeon of Trier settled in the building as a hermit, and the northern gate of the Roman city was subsequently converted into a church.

In the find material, which is kept in the Rhenish State Museum in Trier, a group of curse tablets, which were deposited here in antiquity, is particularly interesting, in addition to stone monuments.

Due to its location, the Circus was destroyed faster than other large Roman buildings in the early Middle Ages, the stones were reused and the area was used for agriculture.

During excavation work for the construction of an underground car park and the main building of the municipal savings bank, the thermal baths were discovered from October 1987.

Parts of the complex are accessible today together with an exposed road in a glass protective structure designed by architect Oswald Mathias Ungers under the Viehmarkt.

In the Middle Ages, the suburb of St. Barbara developed in the partially upright ruins, as well as probably the noble residence of the De Ponte family.

[62] After the discovery of several architectural parts of the 1st century above the temple district in the Altbachtal, an excavation was carried out by the Rheinisches Landesmuseum on the grounds of the Charlottenau estate in 1909/1910.

Several elaborately designed capitals in the Trier Cathedral, which were installed to replace granite columns that had been broken after a fire in the 5th century, may have come as spolia from the temple at the Herrenbrünnchen.

Probably due to the increased water level caused by the narrowing of the river and problems with flooding, the bridge was initially not given a solid stone arch, but a wooden deck that had to be replaced regularly.

Further distribution in the city was by masonry canals lined with waterproof opus signinum aggregate; in the outer districts there is occasional evidence of pipes in wooden logs with iron dike rings.

[72] Already in the 2nd century, a representation and administration area had been created in the northeast of the city by merging four insulae, the core of which was a central hall, which is addressed as the Palace of the Legates.

The remodeling from the beginning of the 4th century in the context of the establishment of the imperial residence is also concentrated in this area, although smaller construction measures in the forum and the streets of the city are attested.

[77] Although the name and appearance of today's Constantine(s) Basilica seem to refer to an ancient church building, the structure was originally built as the reception hall of the imperial residence.

Subsequently, the basilica was rebuilt into a castle-like complex, the apse was closed to the tower, while in the walled interior of the church economic and cellar buildings were created.

Along Windstrasse on the north side of the cathedral, the associated brickwork is still visible to a height of 30 m.[84] The cemeteries of the Middle Imperial Period have only been partially explored and their extent is largely unknown.

Neighboring cities with a Roman past, such as Reims, Toul and Metz, tried in the Middle Ages to trace their mythological foundation back to Remus or the kings Tullus Hostilius or Mettius Rufus.

The supposed tomb inscription of Trebeta is documented in Trier manuscripts since about 1000 and was later adopted in the Gesta Treverorum and the chronicle of Otto von Freising.

In the 15th century, it was turned into the hexameter Ante Romam Treveris stetit annis mille trecentis, which was first inscribed on the Steipe; today it is found on the Red House on Trier's Main Market Square.

The excavations of this period are associated with the names of well-known pioneers of ancient research who worked at the Provinzialmuseum, including Felix Hettner, Hans Lehner, Wilhelm von Massow and Siegfried Loeschcke.

The extensive destruction caused by bomb damage made some areas accessible to archaeology in the post-war period that had previously been overbuilt, such as in the cathedral and the Palastaula.

The traffic-oriented expansion of Trier's city center since the 1960s and other large-scale projects led to the stagnation of scientific reappraisal while financial and personnel resources remained unchanged.