The Bells of Basel

The Bells of Basel (French: Les Cloches de Bâle) is a novel by Louis Aragon, the first in the cycle Le Monde Réel (The Real World), first published in 1934.

From then on, the writer regarded his novels not only as literary works but also as Marxist social analyses aimed at encouraging readers to engage in the labor movement.

[2] Zofia Jaremko-Pytowska emphasizes that the thorough change in Aragon's writing style was related to the realistic literary tradition of France, works in which the psychological analysis of the individual was combined with a detailed description of the social background.

[3] However, Aragon consciously rejected the postulate of neutrality in narration advocated by French realist writers, deciding to make the novel a reflection of his own Marxist political views.

The main character of this part is Diana de Nettencourt, a divorcee, the last descendant of a ruined aristocratic family, a dissolute woman living off the money of successive wealthy lovers.

When one of his clients, Peter de Sabran, a representative of an old aristocratic family, commits suicide, Diana leaves her husband to avoid losing her reputation as an honest woman.

On the last day of the congress, the voice is taken by Clara Zetkin, a member of the German Social Democratic Party, whom Aragon – unlike other women appearing in the work – presents as a woman of the future, truly worthy of praise.

The third part is dedicated to French workers, while the epilogue, resembling the form of a journalistic report,[13] anticipates a better world that the socialist revolution is supposed to bring.

An exemplary case is the character of Brunel, who initially appears as an elegant and well-mannered man but turns out to be capable of murder, a usurer, a police provocateur, and a cynic.

Consequently, both unambiguously negative representatives of the world of financial elites and workers depicted solely in a positive light (although not activists) become schematic characters.

[18] The significance of collective action is emphasized by the construction of scenes involving crowds in the work, depicted in an extremely vivid manner, as a force with a specific goal, not as a disorganized mass.

[19] However, focusing on the general ideology of crowds and their most common beliefs results in a complete abandonment of characterizing individual workers, even achieving their artificial uniformity.

Despite this, The Bells of Basel is an important work in the history of French literature addressing wage laborers: for the first time, the world of workers and associated socialist activists was depicted in such a broad way.

[20] In a review by Georges Sadoul that appeared shortly after the publication of The Bells of Basel, this novel was described as the first example of socialist realism in French literature.

Despite the work being based on clear ideological foundations, Aragon retained many features of surrealist writing in The Bells of Basel, primarily the lack of uniformity in style and the overlapping of plotlines (collage technique).

According to Garaudy, the rhythm of the work is determined by the growing awareness of the inevitability of war and the successive events leading to its outbreak – even when the characters are not directly involved.

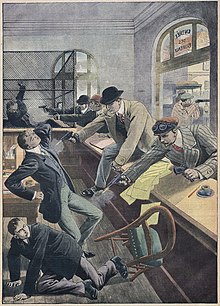

He drew a number of details contained in the work from there: the image of workers' solidarity and attacks on strikebreakers, police provocation, the death of the driver Bédhomme during the demonstration, and his funeral.

[26] Zofia Jaremko-Pytowska, however, offers a different assessment, stating that Aragon saturated this part of the novel with details, wanting to include all his own impressions related to the strike.

However, he admits that the political effects of the congress were different from those assumed, and the described leaders were soon to vote in national parliaments for the granting of war credits to governments, thus contrary to the program of the labor movement.

[2] The first three parts of the novel demonstrate the impossibility of true love in capitalist society, as one of its elements, according to the author, is making women subservient to men.

Only in the finale of the work, when Klara Zetkin speaks, Aragon expresses faith in the rebirth of love that will occur in socialist society when women and men truly become equals.

As Aragon explained in La Nouvelle Critique in 1949:In The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, one sentence struck me, which said that there will come a moment when the best part of the bourgeoisie will join the side of the working class.

Initially, she seeks freedom in anarchism and free love, but the awareness of being dependent on the money sent to her by her father, her sole means of support, makes her realize the futility of these attempts.

Expelled from France, although she makes contact with the British left, she still behaves like an observer of the lives of workers, rather than an active participant,[38] although the narrator suggests that she ultimately adopted socialist views as her own.

Her subsequent changes largely occur under the influence of chance – the character accidentally comes across a procession of striking workers in Cluses, then incidentally sees an anarchist poster, and finally, under similar circumstances, forms a relationship with Victor.

The portrayal of the possessing classes and left-wing activists did not arouse controversy among them, but there were accusations of an unwitting idealization of the anarchist movement in the second part of the work.

[42] Later criticism highly praised especially the first part, as a portrayal of the daily life of the wealthiest French people depicted through a series of seemingly unrelated scenes.