The General Crisis

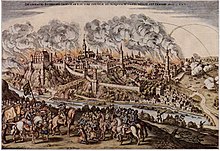

[2] Since the mid-20th century, some scholars have proposed widely different definitions, causes, events, periodisations and geographical applications of a 'General Crisis', disagreeing with each other in debates.

[5] The origin of the concept stems from British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm in his pair of 1954 articles, "The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century", published in Past & Present.

[citation needed] Trevor-Roper argued that the 'violent socio-economic struggles and profound shifts in religious and intellectual values' of the 17th century were caused by the formation of modern nation-states.

[11][12][3] Today there are scholars who promote the crisis model,[13] arguing it provides an invaluable insight into the warfare, politics, economics,[14] and even art of the seventeenth century.

[18] Frederic Wakeman argues that the crisis which destroyed the Ming dynasty was partly a result of the climatic change as well as China's already significant involvement in the developing world economy.

The Qing dynasty's success in dealing with the crisis made it more difficult for it to consider alternative responses when confronted with severe challenges from the West in the 19th century.

[citation needed] Of particular interest is the overlap with the Maunder Minimum, El Niño events and an abnormal spate of volcanic activity.

Although in some areas the early stages of the subsistence crises were not necessarily Malthusian in nature, the result usually followed this model of agricultural deficit in relation to population.

[4] Although protests in the 1630s and 1640s "rose to unusual levels" in some regions, Upton wrote: "Historians have attempted to see in the wave of unrest a 'general crisis', and the debate on this continues.

The main factors arguing against linkage are the reality that the disorders remained specific to local circumstances, even where they coincided in time: they did not coalesce into broader movements.

[4] Almost all of the French princes leading the Fronde (1648–1653) were horrified by the execution of Charles I in 1649, which they regarded as regicide; unlike the majority of English rebels, they never became republicans.

[4] Victor Lieberman argued in 2003, later corroborated by Geoff Wade and Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, that Anthony Reid's "Age of Commerce" Thesis, using Maritime Southeast Asia during the "General Crisis" as a framework to explain Mainland Southeast Asia at this same time, failed to properly address the increased political and economic consolidation and high economic growth of the Southeast Asian mainland states (Siam, Burma, Vietnam) during the 17th through 19th centuries, whose trade connections with China have been argued as to have negated any possible effects of the European departure from the region during the 17th and 18th centuries, therefore the region experienced a relatively calm 17th century in comparison to contemporary regions.

[29][30][31] In 2000, Denis Shemilt used the terms "Industrial Revolution" and especially "General Crisis" as examples of historiographical concepts that are easy to teach adolescent schoolchildren, as they can easily make generalisations about seemingly unconnected events when tasked to do so.