Parmenides (dialogue)

The occasion of the meeting was the reading by Zeno of his treatise defending Parmenidean monism against those partisans of plurality who asserted that Parmenides' supposition that there is a one gives rise to intolerable absurdities and contradictions.

The dialogue is set during a supposed meeting between Parmenides and Zeno of Elea in Socrates' hometown of Athens.

Most scholars agree that the dialogue does not record historic conversations, and is most likely an invention by Plato.

[4] The heart of the dialogue opens with a challenge by Socrates to the elder and revered Parmenides and Zeno.

There is no problem in demonstrating that sensible things may have opposite attributes; what would cause consternation, and earn the admiration of Socrates, would be if someone were to show that the Forms themselves were capable of admitting contrary predicates.

At this point, Parmenides takes over as Socrates' interlocutor and dominates the remainder of the dialogue.

Parmenides suggests that when he is older and more committed to philosophy, he will consider all the consequences of his theory, even regarding seemingly insignificant objects like hair and mud.

Parmenides presses Socrates on how precisely many particulars can participate in a single Form.

(132c–133a) Socrates now suggests that the Forms are patterns in nature (παραδείγματα paradeigmata "paradigms") of which the many instances are copies or likenesses.

He insists that without Forms there can be no possibility of dialectic, and that Socrates was unable to uphold the theory because he has been insufficiently exercised.

The remainder of the dialogue is taken up with an actual performance of such an exercise, where a young Aristoteles (later a member of the Thirty Tyrants, not to be confused with Plato's eventual student Aristotle), takes the place of Socrates as Parmenides' interlocutor.

This difficult second part of the dialogue is generally agreed to be one of the most challenging, and sometimes bizarre, pieces in the whole of the Platonic corpus.

Therefore, since the centre is itself at the same distance from the beginning and the end, the one must have a form: linear, spherical, or mixed.

The one removes from itself the contraries so that it is unnameable, not disputable, not knowable or sensible or showable.

Many thinkers have tried, among them Cornford, Russell, Ryle, and Owen; but few would accept without hesitation any of their characterisations as having got to the heart of the matter.

Recent interpretations of the second part have been provided by Miller (1986), Meinwald (1991), Sayre (1996), Allen (1997), Turnbull (1998), Scolnicov (2003), and Rickless (2007).

It is difficult to offer even a preliminary characterisation, since commentators disagree even on some of the more rudimentary features of any interpretation.

Benjamin Jowett did maintain in the introduction to his translation of the book that the dialogue was certainly not a Platonic refutation of the Eleatic doctrine.

[6] It might even mean that the Eleatic monist doctrine wins over the pluralistic contention of Plato.

[citation needed] The discussion, at the very least, concerns itself with topics close to Plato's heart in many of the later dialogues, such as Being, Sameness, Difference, and Unity; but any attempt to extract a moral from these passages invites contention.

[7] However, the TMA shows that these principles are mutually contradictory, as long as there is a plurality of things that are F: (In what follows, μέγας [megas; "great"] is used as an example; however, the argumentation holds for any F.) Begin, then, with the assumption that there is a plurality of great things, say (A, B, C).

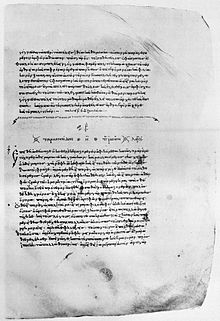

Important examples include those of Proclus and of Damascius, and an anonymous 3rd or 4th commentary possibly due to Porphyry.

The 13th century translation of Proclus' commentary by Dominican friar William of Moerbeke stirred subsequent medieval interest (Klibansky, 1941).

Whosoever undertakes the reading of this sacred book shall first prepare himself in a sober mind and detached spirit, before he makes bold to tackle the mysteries of this heavenly work.

(in Klibansky, 1941)Some scholars (including Gregory Vlastos) believe that the third man argument is a "record of honest perplexity".

Other scholars think that Plato means us to reject one of the premises that produces the infinite regress (namely, One-Over-Many, Self-Predication, or Non-Self-Partaking).

But it is also possible to avoid the contradictions by rejecting Uniqueness and Purity (while accepting One-Over-Many, Self-Predication, and Non-Self-Partaking).