Molniya orbit

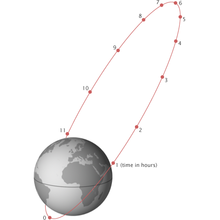

The Molniya orbit has a long dwell time over the hemisphere of interest, while moving very quickly over the other.

In practice, this places it over either Russia or Canada for the majority of its orbit, providing a high angle of view to communications and monitoring satellites covering these high-latitude areas.

Geostationary orbits, which are necessarily inclined over the equator, can only view these regions from a low angle, hampering performance.

[2] Satellites placed in Molniya orbits have been used for television broadcasting, telecommunications, military communications, relaying, weather monitoring, early warning systems and classified surveillance purposes.

[3] Studies found that this could be achieved using a highly elliptical orbit with an apogee over Russian territory.

[3][7] The original Molniya satellites had a lifespan of approximately 1.5 years, as their orbits were disrupted by perturbations, and they had to be constantly replaced.

[1] The succeeding series, the Molniya-2, provided both military and civilian broadcasting and was used to create the Orbita television network, spanning the Soviet Union.

[14] A Russian satellite constellation called Tyulpan was designed in 1994 to support communications at high latitudes, but it did not progress past the planning phase.

[8] In 2015 and 2017 Russia launched two Tundra satellites into a Molniya orbit, despite their name, as part of its EKS early warning system.

To broadcast to these latitudes from a geostationary orbit (above the Earth's equator) requires considerable power due to the low elevation angles, and the extra distance and atmospheric attenuation that comes with it.

Sites located above 81° latitude are unable to view geostationary satellites at all, and as a rule of thumb, elevation angles of less than 10° can cause problems, depending on the communications frequency.

With an apogee altitude as high as 40,000 kilometres (25,000 mi) and an apogee sub-satellite point of 63.4 degrees north, it spends a considerable portion of its orbit with excellent visibility in the northern hemisphere, from Russia as well as from northern Europe, Greenland and Canada.

[2] While satellites in Molniya orbits require considerably less launch energy than those in geostationary orbits (especially launching from high latitudes),[4] their ground stations need steerable antennas to track the spacecraft, links must be switched between satellites in a constellation and range changes cause variations in signal amplitude.

Additionally, there is a greater need for station-keeping,[19][20][21] and the spacecraft will pass through the Van Allen radiation belt four times per day.

[25][26] Permanent high-latitude coverage of a large area of Earth (like the whole of Russia, where the southern parts are about 45° N) requires a constellation of at least three spacecraft in Molniya orbits.

For the original Molniya orbit, the apogees were placed over Russia and North America, but by changing the right ascension of the ascending node this can be varied.

To ensure the geometry relative to the ground stations repeats every 24 hours, the period should be about half a sidereal day, keeping the longitudes of the apogees constant.

), changing the nodal period and causing the ground track to drift over time at the rate shown in equation 2. where

To maximise the amount of time that the satellite spends over the apogee, the eccentricity should be set as high as possible.

However, the perigee needs to be high enough to keep the satellite substantially above the atmosphere to minimize drag (~600km), and the orbital period needs to be kept to approximately half a sidereal day (as above).

[20] To track satellites using Molniya orbits, scientists use the SDP4 simplified perturbations model, which calculates the location of a satellite based on orbital shape, drag, radiation, gravitation effects from the sun and moon, and earth resonance terms.