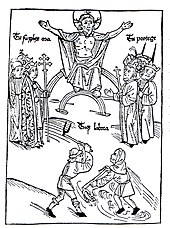

Estates of the realm

[3][4] During the Middle Ages, advancing to different social classes was uncommon and difficult, and when it did happen, it generally took the form of a gradual increase in status over several generations of a family rather than within a single lifetime.

Johan Huizinga observed that "Medieval political speculation is imbued to the marrow with the idea of a structure of society based upon distinct orders".

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, numerous geographic and ethnic kingdoms developed among the endemic peoples of Europe, affecting their day-to-day secular lives; along with those, the growing influence of the Catholic Church and its Papacy affected the ethical, moral and religious lives and decisions of all.

The new lords of the land identified themselves primarily as warriors, but because new technologies of warfare were expensive, and the fighting men required substantial material resources and considerable leisure to train, these needs had to be filled.

The economic and political transformation of the countryside in the period were filled by a large growth in population, agricultural production, technological innovations and urban centers; movements of reform and renewal attempted to sharpen the distinction between clerical and lay status, and power, recognized by the Church also had their effect.

[6] As a result of the Investiture Controversy of the late 11th and early 12th centuries, the powerful office of Holy Roman Emperor lost much of its religious character and retained a more nominal universal preeminence over other rulers, though it varied.

The struggle over investiture and the reform movement also legitimized all secular authorities, partly on the grounds of their obligation to enforce discipline.

The general category of those who labour (specifically, those who were not knightly warriors or nobles) diversified rapidly after the 11th century into the lively and energetic worlds of peasants, skilled artisans, merchants, financiers, lay professionals, and entrepreneurs, which together drove the European economy to its greatest achievements.

This was because it imitated on earth the model set by God for the universe; it was the form of government of the ancient Hebrews and the Christian Biblical basis, the later Roman Empire, and also the peoples who succeeded Rome after the 4th century.

Although there was no formally recognized demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were, effectively, clerical nobility, from Second Estate families.

[9] The "lower clergy" (about equally divided between parish priests, monks, and nuns) constituted about 90 percent of the First Estate, which in 1789 numbered around 130,000 (about 0.5% of the population).

The Third Estate (Tiers état) comprised all of those who were not members of either of the above, and can be divided into two groups, urban and rural, together making up over 98% of France's population.

It was extremely rare for people of this ascribed status to become part of another estate; those who did were usually being rewarded for extraordinary bravery in battle, or entering religious life.

This led to widespread discontent, and produced a group of Third Estate representatives (612 exactly) pressing a comparatively radical set of reforms, much of it in alignment with the goals of acting finance minister Jacques Necker, but very much against the wishes of Louis XVI's court and many of the hereditary nobles who were his Second Estate allies (allies at least to the extent that they were against being taxed themselves and in favour of maintaining high taxation for commoners).

Louis XVI called a meeting of the Estates General to deal with the economic problems and quell the growing discontent, but when he could not persuade them to rubber-stamp his 'ideal program', he sought to dissolve the assembly and take legislation into his own hands.

These independently-organized meetings are now seen as the epoch event of the French Revolution, during which – after several more weeks of civil unrest – the body assumed a new status as a revolutionary legislature, the National Constituent Assembly (July 9, 1789).

[16][full citation needed] This unitary body of former representatives of the three estates began governing, along with an emergency committee, in the power vacuum after the Bourbon monarchy fled from Paris.

Among the Assembly was Maximilien Robespierre, an influential president of the Jacobins who would years later become instrumental in the turbulent period of violence and political upheaval in France known as the Reign of Terror (5 September 1793 – 28 July 1794).

The tradition where the Lords Spiritual and Temporal sat separately from the Commons began during the reign of Edward III in the 14th century.

The clerical proctors elected by the lower clergy of each diocese formed a separate house or estate until 1537, when they were expelled for their opposition to the Irish Reformation.

In addition, four seats as Lords Spiritual were reserved for Church of Ireland clergy: one archbishop and three bishops at a time, alternating place after each legislative session.

Nevertheless, many of the leading politicians of the 19th century continued to be drawn from the old estates, in that they were either noblemen themselves, or represented agricultural and urban interests.

In Finland, it is still illegal and punishable by jail time (up to one year) to defraud into marriage by declaring a false name or estate (Rikoslaki 18 luku § 1/Strafflagen 18 kap.

As a consequence of the Union of Utrecht in 1579 and the events that followed afterwards, the States General declared that they no longer obeyed King Philip II of Spain, who was also overlord of the Netherlands.

After the reconquest of the southern Netherlands (roughly Belgium and Luxemburg), the States General of the Dutch Republic first assembled permanently in Middelburg, and in The Hague from 1585 onward.

Eventually, the Netherlands became part of the French Empire under Napoleon (1810: La Hollande est reunie à l'Empire).

Occasionally, the First and Second Chamber meet in a Verenigde Vergadering (Joint Session), for instance on Prinsjesdag, the annual opening of the parliamentary year, and when a new king is inaugurated.

The Swabian League, a significant regional power in its part of Germany during the 15th Century, also had its own kind of Estates, a governing Federal Council comprising three Colleges: those of Princes, Cities, and Knights.

For instance, English historian of constitutionalism Charles Howard McIlwain wrote that the General Court of Catalonia, during the 14th century, had a more defined organization and met more regularly than the parliaments of England or France.

[25] The roots of the parliament institution in Catalonia are in the Peace and Truce Assemblies (assemblees de pau i treva) that started in the 11th century.