Thylakoid

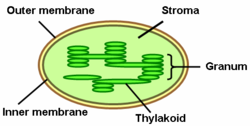

Chloroplast thylakoids frequently form stacks of disks referred to as grana (singular: granum).

Grana are connected by intergranal or stromal thylakoids, which join granum stacks together as a single functional compartment.

For example, acidic lipids can be found in thylakoid membranes, cyanobacteria and other photosynthetic bacteria and are involved in the functional integrity of the photosystems.

[6] Thylakoid membranes are richer in galactolipids rather than phospholipids; also they predominantly consist of hexagonal phase II forming monogalacotosyl diglyceride lipid.

Despite this unique composition, plant thylakoid membranes have been shown to assume largely lipid-bilayer dynamic organization.

During the light-dependent reaction, protons are pumped across the thylakoid membrane into the lumen making it acidic down to pH 4.

A recent electron tomography study of the thylakoid membranes has shown that the stroma lamellae are organized in wide sheets perpendicular to the grana stack axis and form multiple right-handed helical surfaces at the granal interface.

Notably, similar arrangements of helical elements of alternating handedness, often referred to as "parking garage" structures, were proposed to be present in the endoplasmic reticulum[12] and in ultradense nuclear matter.

[13][14][15] This structural organization may constitute a fundamental geometry for connecting between densely packed layers or sheets.

In the plant embryo and in the absence of light, proplastids develop into etioplasts that contain semicrystalline membrane structures called prolamellar bodies.

[16] It is conserved in all organisms containing thylakoids, including cyanobacteria,[17] green algae, such as Chlamydomonas,[18] and higher plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana.

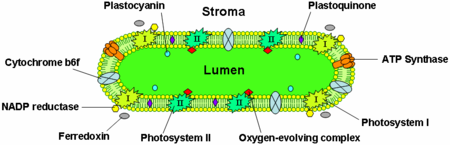

Together, these proteins make use of light energy to drive electron transport chains that generate a chemiosmotic potential across the thylakoid membrane and NADPH, a product of the terminal redox reaction.

These photosystems are light-driven redox centers, each consisting of an antenna complex that uses chlorophylls and accessory photosynthetic pigments such as carotenoids and phycobiliproteins to harvest light at a variety of wavelengths.

Photosystem I contains a pair of chlorophyll a molecules, designated P700, at its reaction center that maximally absorbs 700 nm light.

Photosystem II contains P680 chlorophyll that absorbs 680 nm light best (note that these wavelengths correspond to deep red – see the visible spectrum).

The P is short for pigment and the number is the specific absorption peak in nanometers for the chlorophyll molecules in each reaction center.

However, during the course of plastid evolution from their cyanobacterial endosymbiotic ancestors, extensive gene transfer from the chloroplast genome to the cell nucleus took place.

Plants have developed several mechanisms to co-regulate the expression of the different subunits encoded in the two different organelles to assure the proper stoichiometry and assembly of these protein complexes.

[26] This mechanism involves negative feedback through binding of excess protein to the 5' untranslated region of the chloroplast mRNA.

[28] Thylakoid proteins are targeted to their destination via signal peptides and prokaryotic-type secretory pathways inside the chloroplast.

These include light-driven water oxidation and oxygen evolution, the pumping of protons across the thylakoid membranes coupled with the electron transport chain of the photosystems and cytochrome complex, and ATP synthesis by the ATP synthase utilizing the generated proton gradient.

The water-splitting reaction occurs on the lumenal side of the thylakoid membrane and is driven by the light energy captured by the photosystems.

The molecular mechanism of ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) generation in chloroplasts is similar to that in mitochondria and takes the required energy from the proton motive force (PMF).

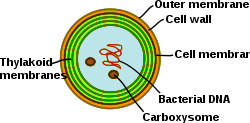

Cyanobacteria have an internal system of thylakoid membranes where the fully functional electron transfer chains of photosynthesis and respiration reside.

Understanding the organization, functionality, protein composition, and dynamics of the membrane systems remains a great challenge in cyanobacterial cell biology.

[31] In contrast to the thylakoid network of higher plants, which is differentiated into grana and stroma lamellae, the thylakoids in cyanobacteria are organized into multiple concentric shells that split and fuse to parallel layers forming a highly connected network.

These gaps in the membrane allow for the traffic of particles of different sizes throughout the cell, including ribosomes, glycogen granules, and lipid bodies.

[32] The relatively large distance between the thylakoids provides space for the external light-harvesting antennae, the phycobilisomes.