Ticks of domestic animals

Ticks pierce the skin of their hosts with specialized mouthparts to suck blood, and they survive exclusively by this obligate method of feeding.

In addition to Rhipicephalus microplus, species of most importance to domestic animals are R. annulatus, which is widespread in tropical and subtropical countries, and R. decoloratus which occurs in Africa.

The engorged female drops from the host, hides under leaf litter on soil surface, lays one batch of eggs, and then dies.

[citation needed] This genus contains many species of hard ticks important to domestic animals in hot, dry regions in Africa, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, Pakistan, India,[7] and through to China.

[citation needed] Other genera with species that are often of high local importance to domestic animals include the following examples, some of which are illustrated in the gallery below.

These two losses result in reduced feed intake and anemia; combined, they cause a lower rate of growth or of milk production compared to hosts without tick infestation.

Larger ticks cause obstructive and painful damage, such as Amblyomma variegatum adults, which often feed on udders of cattle and reduce suckling by the calves.

Wounds caused by dense clusters of adult ticks can make the host susceptible to infestation with larvae of flesh-eating myiasis flies, such as the screw-worm, Cochliomyia hominivorax.

[10][11] When ticks feed, they secrete saliva containing powerful enzymes and substances with strong pharmacological properties to maintain flow of blood and reduce host immunity.

The skin disease dermatophilosis of cattle, sheep, and goats is caused by the bacterium Dermatophilus congolensis, which is transmitted by simple contagion.

When Amblyomma variegatum adult ticks are also feeding and causing a systemic suppression of immunity in the host, then dermatophilosis becomes severe or even fatal.

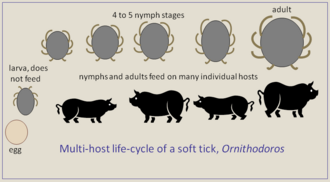

African swine fever is naturally transmitted between wild species of the pig family by feeding of Ornithodoros moubata group ticks.

In cattle and sheep, it causes mild fever and its main importance is when it spreads to humans (zoonosis) by feeding of the larvae or nymphs of these ticks.

Borrelia anserina is transmitted by Argas persicus to poultry, causing avian borreliosis in a wide spread of tropical and subtropical countries.

[19] Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) is a bacterium of deer that spreads to sheep where it causes tick-borne fever in Europe, resulting in abortion by ewes and temporary sterility of rams.

This depletes these antibacterial cells and renders the host susceptible to opportunistic infections by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria which invade joints and cause the crippling disease of sheep called tick pyaemia.

Anaplasma marginale infects marginal areas of red blood cells of cattle and causes anaplasmosis wherever boophilid ticks occur as transmitters.

Heartwater also occurs on the Caribbean islands, having spread there on shipments of cattle from Africa about 150 years ago, before anything was known of tick transmitted microbes.

[11][20] Babesia bovis protozoa are transmitted by R. microplus and cause babesiosis or redwater fever in cattle throughout the tropics and subtropics wherever this boophilid species occurs.

The development of Theileria in ticks includes sexual reproduction which enables generation of new variants that can evade the immune mechanisms of cattle.

These are now replaced by various synthetic chemicals of high specificity for acarines and ticks, and farmers frequently rely on treating their animals with these materials as their default method.

[24] Synthetic chemical pesticides specific for ticks (acaricides) are suspended in water for application to the hair coat of domestic animals.

Nicotine from treated tobacco leaf is an example, but such unregistered preparations require careful use to avoid poisoning or skin damage.

[30] Eradication of ticks, as total removal of all populations of a species over a wide geographical area defined by natural boundaries, has been attempted several times.

The nymphs and adults of three-host ticks, such as Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus species, can live for many months to a year or more, respectively, whilst questing on the vegetation.

In addition, farmers find the priority to provide their stock with good feed often conflicts with the regimens for pasture rotation for tick control.

[2][39] Food reserves for survival of off-host ticks include large membrane-bound vesicles of lipid in the digestive cells of their gut.

Further adaptations include a thick integument with waxy waterproofing combined with ability to secrete hygroscopic salts from specialized parts of their salivary glands (type 1 acini) out to the exterior of their mouthparts and then suck back in the watery solution that develops around the salty material.

In addition, some species of protozoans (within the Theileria and Babesia genera), are able to infect ticks even when they exist in the blood of their hosts at such a low level that no signs of disease can be detected.

[54] This is made by serial infection of calves to attenuate the virulence of the strain of Babesia, followed by splenectomy to produce many of the piroplasm stage in blood, which is then bottled for use.