Odin

Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg.

Odin is frequently portrayed as one-eyed and long-bearded, wielding a spear named Gungnir or appearing in disguise wearing a cloak and a broad hat.

He is often accompanied by his animal familiars—the wolves Geri and Freki and the ravens Huginn and Muninn, who bring him information from all over Midgard—and he rides the flying, eight-legged steed Sleipnir across the sky and into the underworld.

In these texts he frequently seeks greater knowledge, most famously by obtaining the Mead of Poetry, and makes wagers with his wife Frigg over his endeavors.

[11] As of 2011, an attestation of Proto-Norse Woðinz, on the Strängnäs stone, has been accepted as probably authentic, but the name may be used as a related adjective instead meaning "with a gift for (divine) possession" (ON: øðinn).

[12] Other Germanic cognates derived from *wōðaz include Gothic woþs ('possessed'), Old Norse óðr ('mad, frantic, furious'), Old English wōd ('insane, frenzied') and Dutch woed ('frantic, wild, crazy'), along with the substantivized forms Old Norse óðr ('mind, wit, sense; song, poetry'), Old English wōþ ('sound, noise; voice, song'), Old High German wuot ('thrill, violent agitation') and Middle Dutch woet ('rage, frenzy'), from the same root as the original adjective.

[13] The adjective *wōðaz ultimately stems from a Pre-Germanic form *uoh₂-tós, which is related to the Proto-Celtic terms *wātis, meaning 'seer, sooth-sayer' (cf.

[9][10] In the case a borrowing scenario is excluded, a PIE etymon *(H)ueh₂-tis ('prophet, seer') can also be posited as the common ancestor of the attested Germanic, Celtic and Latin forms.

The first clear example of this occurs in the Roman historian Tacitus's late 1st-century work Germania, where, writing about the religion of the Suebi (a confederation of Germanic peoples), he comments that "among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship.

Regarding the Germanic peoples, Caesar states: "[T]hey consider the gods only the ones that they can see, the Sun, Fire and the Moon", which scholars reject as clearly mistaken, regardless of what may have led to the statement.

Dated to as early as the 400s, the bracteate features a Proto-Norse Elder Futhark inscription reading "He is Odin’s man" (iz Wōd[a]nas weraz).

ōs byþ ordfruma ǣlcre sprǣce wīsdōmes wraþu and wītena frōfur and eorla gehwām ēadnys and tō hiht[32] god is the origin of all language wisdom's foundation and wise man's comfort and to every hero blessing and hope[32] The first word of this stanza, ōs (Latin 'mouth') is a homophone for Old English os, a particularly heathen word for 'god'.

Luckily for Christian rune-masters, the Latin word os could be substituted without ruining the sense, to keep the outward form of the rune name without obviously referring to Woden.

[46] Odin is mentioned or appears in most poems of the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from traditional source material reaching back to the pagan period.

The poem Völuspá features Odin in a dialogue with an undead völva, who gives him wisdom from ages past and foretells the onset of Ragnarök, the destruction and rebirth of the world.

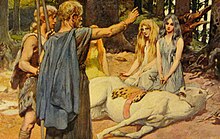

Among the information the völva recounts is the story of the first human beings (Ask and Embla), found and given life by a trio of gods; Odin, Hœnir, and Lóðurr: In stanza 17 of the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá, the völva reciting the poem states that Hœnir, Lóðurr and Odin once found Ask and Embla on land.

This advice ranges from the practical ("A man shouldn't hold onto the cup but drink in moderation, it's necessary to speak or be silent; no man will blame you for impoliteness if you go early to bed"), to the mythological (such as Odin's recounting of his retrieval of Óðrœrir, the vessel containing the mead of poetry), and to the mystical (the final section of the poem consists of Odin's recollection of eighteen charms).

Odin is introduced in chapter two, where he is said to have lived in "the land or home of the Æsir" (Old Norse: Ásaland eða Ásaheimr), the capital of which being Ásgarðr.

Local legend dictates that after it was opened, "there burst forth a wondrous fire, like a flash of lightning", and that a coffin full of flint and a lamp were excavated.

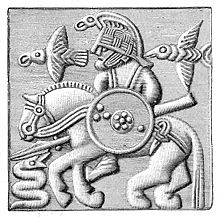

Migration Period (5th and 6th century CE) gold bracteates (types A, B, and C) feature a depiction of a human figure above a horse, holding a spear and flanked by one or two birds.

[78] A pair of identical Germanic Iron Age bird-shaped brooches from Bejsebakke in northern Denmark may be depictions of Huginn and Muninn.

"[81] A portion of Thorwald's Cross (a partly surviving runestone erected at Kirk Andreas on the Isle of Man) depicts a bearded human holding a spear downward at a wolf, his right foot in its mouth, and a large bird on his shoulder.

[85] The Younger Futhark inscription on the stone bears a commonly seen memorial dedication, but is followed by an encoded runic sequence that has been described as "mysterious,"[86] and "an interesting magic formula which is known from all over the ancient Norse world.

Odin had the power to lay bonds upon the mind, so that men became helpless in battle, and he could also loosen the tensions of fear and strain by his gifts of battle-madness, intoxication, and inspiration.

The idea was developed by Bernhard Salin on the basis of motifs in the petroglyphs and bracteates, and with reference to the Prologue of the Prose Edda, which presents the Æsir as having migrated into Scandinavia.

[89] More radically, both the archaeologist and comparative mythologist Marija Gimbutas and the Germanicist Karl Helm argued that the Æsir as a group, which includes both Thor and Odin, were late introductions into Northern Europe and that the indigenous religion of the region had been Vanic.

[90][91] In the 16th century and by the entire Vasa dynasty, Odin (Swedish: Oden) was officially considered the first king of Sweden by that country's government and historians.

[95] He has also been interpreted in the light of his association with ecstatic practices, and Jan de Vries compared him to the Hindu god Rudra and the Greek Hermes.

August 1870 (1870) by Richard Wagner, the ballad Rolf Krake (1910) by F. Schanz, the novel Juvikingerne (1918–1923) by Olav Duun, the comedy Der entfesselte Wotan (1923) by Ernst Toller, the novel Wotan by Karl Hans Strobl, Herrn Wodes Ausfahrt (1937) by Hans-Friedrich Blunck, the poem An das Ich (1938) by H. Burte, and the novel Sage vom Reich (1941–1942) by Hans-Friedrich Blunck.

[98] Music inspired by or featuring the god includes the ballets Odins Schwert (1818) and Orfa (1852) by J. H. Stunz and the opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1848–1874) by Richard Wagner.