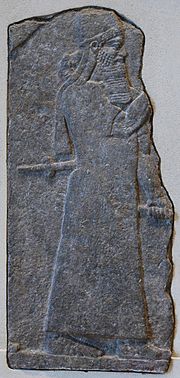

Tiglath-Pileser III

Because of the massive expansion and centralization of Assyrian territory and establishment of a standing army, some researchers consider Tiglath-Pileser's reign to mark the true transition of Assyria into an empire.

The reforms and methods of control introduced under Tiglath-Pileser laid the groundwork for policies enacted not only by later Assyrian kings but also by later empires for millennia after his death.

This victory was significant since Urartu had for a brief time equalled Assyrian power; Sarduri had eleven years earlier defeated Tiglath-Pileser's predecessor Ashur-nirari.

[6] The Assyriologist Paul Garelli considers this unlikely, given that 38 years separate the reign of Adad-nirari from that of Tiglath-Pileser, writing that the possibility of him being Ashur-nirari's son cannot be fully ruled out.

[16] In her 2016 PhD thesis, the historian Tracy Davenport advanced the theory that Tiglath-Pileser might have been entirely legitimate and that he could even have co-ruled with Ashur-nirari for some time.

If Ashur-nirari did rule until 744, it is unlikely that there was a civil war, since Tiglath-Pileser is recorded to have gone on campaigns against Assyria's foreign enemies in this time, not possible if he was simultaneously involved in internal conflict.

[29] Assyria first rose as a prominent state under the Middle Assyrian Empire in the 14th century BC, previously only having been a city-state centered on the city of Assur.

[35] Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC) further expanded Assyrian territory but his enlarged domain proved difficult to stabilize and his last few years initiated a renewed period of stagnation and decline, marked by both external and internal conflict.

[36] The most important problems facing Shalmaneser late in his reign were the rise of the kingdom of Urartu in the north and the increasing political authority and influence of the "magnates", a set of influential Assyrian courtiers and officials.

[2] The Assyrian kings were unable to deal with external threats since the magnates had gradually become the dominant political actors and central authority had become very weak.

Some historically prominent officials, such as the turtanu Shamshi-ilu, were subjected to damnatio memoriae, with their names being deliberately erased from inscriptions and documents.

Though Tiglath-Pileser's conquests generated a massive amount of revenue, he appears to have invested little of it into the Assyrian heartland itself; the only known building work conducted by him was a new palace in Nimrud.

Though previous kings had resettled people, Tiglath-Pileser's reign saw the beginning of frequent mass deportations, a policy which continued under his successors.

There were two intended goals of this policy: firstly to reduce the local identities in conquered regions, to counteract the risk of revolt, and secondly to recruit and move laborers to where the Assyrian kings needed them, such as underdeveloped and underutilized provinces.

[42] Though Tiglath-Pileser recorded his military exploits in great detail in his "annals", written on sculpted stone slabs decorating his palace in Nimrud, these are poorly preserved,[27] meaning that for several of his campaigns it is only possible to produce a broad outline.

Unlike the Assyrian defeat by Arpad eleven years earlier, Tiglath-Pileser won the battle,[2][42] one of the greatest triumphs of his reign.

The early conquests brought coastal and flat lands under his rule, which meant that Assyrian troops in the later campaigns could march through the region fast and efficiently.

[42][52] This campaign resulted in the conquest of Gaza and the submission of numerous states, effectively bringing the entire Levant under direct or indirect Assyrian rule;[56] Assyria and Egypt shared a border for the first time in history.

[57] Asqaluna, Judah, Edom, Moab and Ammon, and the Mu’na Arab tribe, all began paying tribute to Tiglath-Pileser.

In this year, he again campaigned against Aram-Damascus, still the strongest remaining native state in the region, which was supported by the Assyrian tributaries Tyre and Asqaluna, as well as Israel.

[2] The weakening and enormous reduction in size of Israel was seen by the Israelites as vindicating predictions of impending doom made by the prophet Amos a few decades prior.

[42] The massive western expansion of Assyria brought Tiglath-Pileser and his armies into direct contact with Arab tribes, several of whom began paying tribute.

[61] Though Tiglath-Pileser was victorious, he realized that he would not be able to effectively govern the territories ruled by the Qedarites and thus allowed Samsi to remain in control of her domain, though under the supervision of an Assyrian official to guide her political actions.

[63] Babylonia had once been a large and hugely influential kingdom, competing with Assyria for centuries,[64] but during the Neo-Assyrian period it was typically weaker than its northern neighbor.

In this year, Assyrian envoys are recorded travelling to Babylon and urging the inhabitants to open their gates and surrender to Tiglath-Pileser, stating that the king would grant them amnesty and tax privileges.

[69] Because of this respect and because Babylonia was showing signs of the beginning of an economic recovery, Tiglath-Pileser worked to conciliate the populace to the idea of Assyrian overlordship.

He twice participated in the religiously important New Years' Akitu festival, which required the presence of the king, and also led campaigns against remaining Chaldean strongholds in the far south who resisted his rule.

[63] Several Assyriologists consider Assyria to only truly have transitioned into an "empire" in a strict sense during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser,[28][63][82][83] owing to its unprecedented size, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual character and the new mechanisms of economic and political control.

First and foremost, it led to significant improvements in irrigation in the provinces, owing to deportees being tasked to introduce Assyrian-developed agricultural techniques to their new communities, and to an increase in prosperity across the empire.

[49] In the long term, the movement of peoples from across the empire changed the cultural and ethnic makeup of the Middle East forever and in time led to the rise of Aramaic as the region's lingua franca,[47] a position the language retained until the 14th century AD.