Balance spring

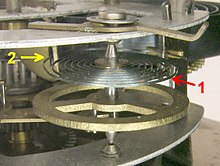

A regulator lever is often fitted, which can be used to alter the free length of the spring and thereby adjust the rate of the timepiece.

The balance spring is a fine spiral or helical torsion spring used in mechanical watches, alarm clocks, kitchen timers, marine chronometers, and other timekeeping mechanisms to control the rate of oscillation of the balance wheel.

The addition of the balance spring to the balance wheel around 1657 by Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens greatly increased the accuracy of portable timepieces, transforming early pocketwatches from expensive novelties to useful timekeepers.

Improvements to the balance spring are responsible for further large increases in accuracy since that time.

Modern balance springs are made of special low temperature coefficient alloys like nivarox to reduce the effects of temperature changes on the rate, and carefully shaped to minimize the effect of changes in drive force as the mainspring runs down.

[2][3] Before that time, balance wheels or foliots without springs were used in clocks and watches, but they were very sensitive to fluctuations in the driving force, causing the timepiece to slow down as the mainspring unwound.

[6] In the Tompion regulator the curb pins were mounted on a semicircular toothed rack, which was adjusted by fitting a key to a cog and turning it.

Moving the regulator slides the slot along the outer turn of the spring, changing its effective length.

There are two principal types of balance spring regulator: There is also a hog's hair or pig's bristle regulator, in which stiff fibres are positioned at the extremities of the balance's arc and bring it to a gentle halt before throwing it back.

Early on, steel was used, but without any hardening or tempering process applied; as a result, these springs would gradually weaken and the watch would start losing time.

Hardened and tempered steel was first used by John Harrison and subsequently remained the material of choice until the 20th century.

In 1833, E. J. Dent (maker of the Great Clock of the Houses of Parliament) experimented with a glass balance spring.

Other trials with glass springs revealed that they were difficult and expensive to make, and they suffered from a widespread perception of fragility, which persisted until the time of fibreglass and fibre-optic materials.

[8] Hairsprings made of etched silicon were introduced in the late 20th century and are not susceptible to magnetisation.

The earliest makers of watches with balance springs, such as Hooke and Huygens, observed this effect without finding a solution to it.

Harrison, in the course of his development of the marine chronometer, solved the problem by a "compensation curb" – essentially a bimetallic thermometer which adjusted the effective length of the balance spring as a function of temperature.

While this scheme worked well enough to allow Harrison to meet the standards set by the Longitude Act, it was not widely adopted.

Various "auxiliary compensation" mechanisms were designed to avoid this, but they all suffer from being complex and hard to adjust.

This simplifies the mechanism, and it also means that middle temperature error is eliminated as well, or at a minimum is drastically reduced.

A balance spring obeys Hooke's Law: the restoring torque is proportional to the angular displacement.

This is particularly true in watches and portable clocks which are powered by a mainspring, which provides a diminishing drive force as it unwinds.

Early watchmakers empirically found approaches to make their balance springs isochronous.

In general practice, the most common method of achieving isochronism is through the use of the Breguet overcoil, which places part of the outermost turn of the hairspring in a different plane from the rest of the spring.

This allows the hairspring coil to expand and contract more evenly and symmetrically as the balance wheel rotates.

The Z-bend does this by imposing two kinks of complementary 45 degree angles, accomplishing a rise to the second plane in about three spring section heights.

Due to the difficulty with forming an overcoil, modern watches often use a slightly less effective "dogleg", which uses a series of sharp bends (in plane) to place part of the outermost coil out of the way of the rest of the spring.

- flat spiral

- Breguet overcoil

- chronometer helix [ 1 ] showing curving ends,

- early balance springs