Tipping points in the climate system

[4][5] Tipping behavior is found across the climate system, for example in ice sheets, mountain glaciers, circulation patterns in the ocean, in ecosystems, and the atmosphere.

[5] Examples of tipping points include thawing permafrost, which will release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, or melting ice sheets and glaciers reducing Earth's albedo, which would warm the planet faster.

For example, with average global warming somewhere between 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) and 3 °C (5.4 °F), the Greenland ice sheet passes a tipping point and is doomed, but its melt would take place over millennia.

Sustained warming of the northern high latitudes as a result of this process could activate tipping elements in that region, such as permafrost degradation, and boreal forest dieback.

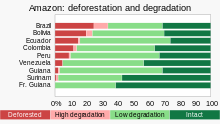

Lastly, the tipping points in terrestrial systems include Amazon rainforest dieback, boreal forest biome shift, Sahel greening, and vulnerable stores of tropical peat carbon.

[35][36][37] The paleo record suggests that during the past few hundred thousand years, the WAIS largely disappeared in response to similar levels of warming and CO2 emission scenarios projected for the next few centuries.

[46][47] This tipping point matters because of the decade-long history of research into the connections between the state of Barents-Kara Sea ice and the weather patterns elsewhere in Eurasia.

It is believed that one third of that ice will be lost by 2100 even if the warming is limited to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), while the intermediate and severe climate change scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 4.5 and 8.5) are likely to lead to the losses of 50% and >67% of the region's glaciers over the same timeframe.

[58][59][60] Perennially frozen ground, or permafrost, covers large fractions of land – mainly in Siberia, Alaska, northern Canada and the Tibetan plateau – and can be up to a kilometre thick.

[66] Because CO2 and methane are both greenhouse gases, they act as a self-reinforcing feedback on permafrost thaw, but are unlikely to lead to a global tipping point or runaway warming process.

[13] In 2021, a study which used a primitive finite-difference ocean model estimated that AMOC collapse could be invoked by a sufficiently fast increase in ice melt even if it never reached the common thresholds for tipping obtained from slower change.

This would result in rapid cooling, with implications for economic sectors, agriculture industry, water resources and energy management in Western Europe and the East Coast of the United States.

[85][86] Some of this has been due to the natural cycle of Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation,[87][88] but climate change has also played a substantial role in both trends, as it had altered the Southern Annular Mode weather pattern,[89][87] while the massive growth of ocean heat content in the Southern Ocean[90] has increased the melting of the Antarctic ice sheets, and this fresh meltwater dilutes salty Antarctic bottom water.

Subsequent research in Canada found that even in the forests where biomass trends did not change, there was a substantial shift towards the deciduous broad-leaved trees with higher drought tolerance over the past 65 years.

[111] A 2018 study of the seven tree species dominant in the Eastern Canadian forests found that while 2 °C (3.6 °F) warming alone increases their growth by around 13% on average, water availability is much more important than temperature.

[117]: 267 A study from 2022 concluded: "Clearly the existence of a future tipping threshold for the WAM (West African Monsoon) and Sahel remains uncertain as does its sign but given multiple past abrupt shifts, known weaknesses in current models, and huge regional impacts but modest global climate feedback, we retain the Sahel/WAM as a potential regional impact tipping element (low confidence).

[133] It was suggested that this finding could help explain past episodes of unusually rapid warming such as Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum[134] In 2020, further work from the same authors revealed that in their large eddy simulation, this tipping point cannot be stopped with solar radiation modification: in a hypothetical scenario where very high CO2 emissions continue for a long time but are offset with extensive solar radiation modification, the break-up of stratocumulus clouds is simply delayed until CO2 concentrations hit 1,700 ppm, at which point it would still cause around 5 °C (9.0 °F) of unavoidable warming.

Sustained warming of the northern high latitudes as a result of this process could activate tipping elements in that region, such as permafrost degradation, and boreal forest dieback.

[147] Methane hydrate deposits in the Arctic were once thought to be vulnerable to a rapid dissociation which would have a large impact on global temperatures, in a dramatic scenario known as a clathrate gun hypothesis.

[153][154] Bifurcation-induced tipping happens when a particular parameter in the climate (for instance a change in environmental conditions or forcing), passes a critical level – at which point a bifurcation takes place – and what was a stable state loses its stability or simply disappears.

[162][163] These EWSs are often developed and tested using time series from the paleo record, like sediments, ice caps, and tree rings, where past examples of tipping can be observed.

Some potential tipping points would take place abruptly, such as disruptions to the Indian monsoon, with severe impacts on food security for hundreds of millions.

[5][174][175] The impacts of AMOC collapse would have serious implications for food security, with one projection showing reduced yields of key crops across most world regions, with for example arable agriculture becoming economically infeasible in Britain.

[148] A review of abrupt changes over the last 30,000 years showed that tipping points can lead to a large set of cascading impacts in climate, ecological and social systems.

For instance, the abrupt termination of the African humid period cascaded, and desertification and regime shifts led to the retreat of pastoral societies in North Africa and a change of dynasty in Egypt.

[164] Some scholars have proposed a threshold which, if crossed, could trigger multiple tipping points and self-reinforcing feedback loops that would prevent stabilisation of the climate, causing much greater warming and sea-level rises and leading to severe disruption to ecosystems, society, and economies.

However, while this scenario is possible, the existence and value of this threshold remains speculative, and doubts have been raised if tipping points would lock in much extra warming in the shorter term.

[179][180] Decisions taken over the next decade could influence the climate of the planet for tens to hundreds of thousands of years and potentially even lead to conditions which are inhospitable to current human societies.

A runaway greenhouse effect is a tipping point so extreme that oceans evaporate[182] and the water vapour escapes to space, an irreversible climate state that happened on Venus.

[184][further explanation needed] Venus-like conditions on the Earth require a large long-term forcing that is unlikely to occur until the sun brightens by a ten of percents, which will take 600 - 700 million years.