Toronto ravine system

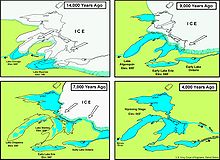

The Toronto ravine system originated approximately 12,000 years ago at the end of the Last Glacial Period, with rivers and valleys being formed in the wake of the retreating glaciers and the compressed land it left.

[4][6] Most of the meltwater flowed southeast along shallow ice-scrapped depressions towards the glacial lake, creating small ponds north of Toronto.

[8] The new lake existed until approximately 8,000 years ago, when the Earth's crust around Quebec and northeastern Ontario began to rebound, having been previously depressed under the weight of the glacial ice that had since retreated from that area.

[10] The ravine system also saw significant alterations as a result of human activity in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as several natural valleys were filled in, rivers rechannelled or buried entirely, and wetlands drained to facilitate new developments.

[11] As a result of these changes, the Don River and a small portion of Taddle Creek were the only remaining waterways that flowed into Toronto Bay by the mid-20th century.

[20][21][22] The edge of the ravine system throughout the city collectively amounts to over 1,200 kilometres (750 mi), ten times the length of the Toronto waterfront.

[23] Most of the ravine system remains in a naturalized state for flood control purposes, given the high variability in the water levels of the rivers and streams.

[1] The point where the Humber, Don, and Rouge River watersheds meet is near the intersection of Bathurst Street and Jefferson Sideroad at the Vaughan-Richmond Hill boundary.

[24] The shape of streams within the ravine system is subject to constant change, with large storms causing the area to flood, and erosion to occur on river banks and meanders.

[32] In addition to providing a habitat in an urban environment, the ravine system also acts as a wildlife corridor, permitting the animals that live within it to travel from one area of the city to another.

[33] The corridors are of particular importance for wild mammals, as they provide the only safe passage for them to traverse from one part of the city to another to find new mates and establish their own homes.

[6] Most flora that is native to the area, such as the oak, have the genetic diversity that makes them more adaptable and resilient to extreme climate events and pest infestations.

[31] In a 2018 study on the ravine system's ecology, at least one of 15 identified high-risk invasive plant species was found in 75 per cent of areas surveyed.

[36] After the introduction of corn in southern Ontario circa 500 CE, the ancestral Wyandot peoples began to raise the crop by clearing the floodplains.

[40][39] The first Europeans to arrive in the area were primarily explorers, fur traders, and missionaries, with a French Sulpician mission established at the mouth of the Rouge River by 1669.

[42] Due to the limited lumber supply the British had during the Napoleonic Wars, and the abundance of old-growth pines in the ravine system, portions of the Rouge Valley were logged to support the Royal Navy's shipbuilding efforts.

[11][20] Clay excavations at the Don Valley Brick Works have provided researchers with the best-known preserved interglacial record in northern North America.

[2] By the mid-19th century, the Don Valley gained a reputation as a "space for undesirables," with residents of the city perceiving the ravine as an area that harboured and facilitated lawlessness.

[47] During the late 19th century several wetlands and lagoons at the mouths of the Don River were infilled, as the shallowness of Ashbride's Marsh made the area optimal for redevelopment as the Port Lands.

[28] Many of the homes that were destroyed were situated in the rechannelled rivers and streams of the ravine system, areas already threatened by flooding from heavy rainfalls.

[42][54] The municipal government proceeded with its plan to create several parks in the ravine system, although they were built further upstream, adjacent to the TRCA's designated reservoirs and watersheds.

In 2001, The Globe and Mail ran a three-part series titled "The Outsiders"[56] tracing the life of the homeless residents of the ravines for nearly a year.

[59] Eco-services provided by the ravine include aesthetics, carbon sequestration, flood mitigation, the regulation of temperature and noise, and recreation.

[60] Work on new bypass tunnels to capture combined sewer overflows and prevent their flow into the Don River and Lake Ontario was undertaken beginning in December 2019.

[64] As of July 2019, the park has incorporated 95 per cent of the 79.1 square kilometres (30.5 sq mi) of land committed to it by the municipal, provincial, and federal governments.

[70] It has been suggested that ravines are featured in several works set in Toronto because they are "the chief characteristic of the local terrain" and a "topographical signature" of the city.

[72] This includes literary works like Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle, which depicts the ravines as a meeting place where the unruly dense wilderness collided with the tidy streets of suburban Toronto.

[74] According to Robert Fulford, because the ravines are a "tangible (though often hidden) part of [Toronto's] surroundings and a persistent force in [its] civic imagination", they form a "shared subconscious of the municipality," and is therefore where most of the local literature is born from.

However, authors in the late-20th century, including Anne Michaels and Catherine Bush, have portrayed the ravine system in a positive light, as a place of healing and sanctuary from civic life.

[70] Other artists and authors that have highlighted the Toronto ravine system in their works include Morley Callaghan, Douglas Anthony Cooper, Ernest Hemingway, and Doris McCarthy.