Trần Ngọc Châu

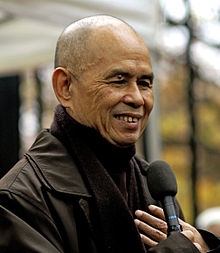

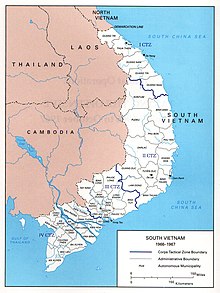

Tran Ngoc Châu (1 January 1924 – 17 June 2020) was a Vietnamese soldier (Lieutenant Colonel), civil administrator (city mayor, province chief), politician (leader of the Lower House of the National Assembly), and later political prisoner, in the Republic of Vietnam until its demise with the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

[1] Tran Ngoc Châu was born in 1923 or 1924 into a Confucian–Buddhist family of government officials (historically called mandarins, quan in Vietnamese),[2][3] who lived in the ancient city of Huế, then the imperial capital, on the coast of central Vietnam.

[15] Here Châu mixed with peasants and workers for the first time, experiencing "the great gap between the privileged... and the underprivileged" and the "vital role" played by the rural villagers in Vietnam's destiny.

"[34] After four years spent mostly in the countryside and forest; the soldier Châu, eventually came to a state of disagreement with the resistance leadership when he learned of its half-hidden politics, and what he took to be the communist vision for Vietnam's future.

Although the Việt Minh was then widely considered to represent a popular nationalism, Châu objected to its core communist ideology which rejected many Vietnamese customs, traditional family ties, and the Buddhist religion.

[62][63][64] During the transition from French rule to full independence Ngô Đình Diệm,[65] the President of the Republic, although making costly mistakes managed to lead the southern state through a precarious stage in the establishment of its sovereignty.

Instead Diệm spoke at length of his high regard for Châu's mandarin grandfather the state minister Tran Tram, for his father and his accomplished family in Huế, the former Vietnamese capital.

[94] Diệm had told Châu that his job was extremely important as the popular reputation of the Civil Guard in the countryside largely influenced how most people thought about the entire military.

"[100] Yet despite the efforts made, Châu sensed that a "great opportunity" was being missed: to build a national élan among the country people of South Vietnam that would supplant the vapid air of the French holdovers, and to reach out to former Việt Minh in order to rally them to the government's side.

Among other things, Châu found that, in contrast to Vietnam, in Malaysia (a) civilian officials controlled pacification rather than the military, (b) when arresting quasi-guerrillas certain legal procedures were followed, and (c) government broadcasts were more often true than not.

[127][128][129][130][131] It was Châu's frank appraisal of the conspiring generals, e.g., Dương Văn Minh, that these prospective new rulers were Diệm's inferiors, in moral character, education, patriotic standing, and leadership ability.

[179] In Kiến Hòa Province, Châu began to personally train several different kinds of civil-military teams in the skills needed to put the procedures into practice.

Châu's teams were instructed how to learn from villagers about the details and identities of their security concerns, and then to work to turn the allegiance or to neutralize the communist party apparatus, which harbored the VC fighters.

"[199][200] In Kiến Hòa Province, Châu begin to train five types of specialized teams: census grievance (interviews), social development, open arms (Viet Cong recruitment), security, and counterterror.

"As our intelligence grew in volume and accuracy, Viet Cong members no longer found it easy to blend into the general populace during the day and commit terrorist acts by night."

Komer had concluded that the bureaucratic position of CORDS should be within the American "chain of command" of MACV, which would provide for U.S Army support, access to funding, and the attention of policy makers.

[251][252][253] Controversy surrounded the Phoenix Program on different issues, e.g., its legality (when taking direct action against ununiformed communist cadres doing social-economic support work), its corruption by such exterior motives of profit or revenge (which led to the unwarranted use of violence including the killing of bystanders), and the extent of its political effectiveness against the Viet Cong infrastructure.

In constructing Phoenix, the CIA then CORDS had collected components from the various pacification efforts ongoing in Vietnam, then re-assembled them into a variegated program that never achieved the critical, interlocking coherence required to rally the Vietnamese people.

During his career as an army officer, Châu had served in several major civilian posts: as governor of Kiến Hòa Province (twice), and as mayor of Da Nang the second largest city.

[312][313][314][315][316] Then in the spring of 1966, the Buddhist struggle movement led by Thích Trí Quang[317] obligated the military government to agree to democratic national elections, American style, in 1966 and 1967.

The campaigns leading to the October 1967 vote were unfamiliar phenomena in South Vietnam, and called on Châu to make difficult decisions on strategy and regarding innovation in the field.

He was sincere in his desire to improve the lives of the peasantry, even if the system he served did not permit him to follow through in deed, and his four years in the Việt Minh and his highly intelligent and complicated mind enabled him to discuss guerrilla warfare, pacification, the attitude of the rural population, and the flaws in Saigon society with insight and wit.

Accordingly, a major source of wealth was the import of vast quantities of American goods: to support military operations, to supply hundreds of thousands of troops, and to mitigate 'collateral damage'.

"[409] [Under construction] In 1970, Châu was arrested for treason against the Republic due to his meeting with his brother Hien, who had since the 1940s remained in the Việt Minh and subsequent communist organizations as a party official.

The first three months the prisoners worked constructing and fixing up the camp itself: "sheet-iron roofs, corrugated metal walls, and cement floors", all surrounded by concertina wire and security forces.

[448][449][450] In the late 1970s top Communist leaders in the north seemed to understand victory in the exhausting war as the fruit of their efforts, their suffering, which entitled northern party members to privileges as permanent officials in the south.

[473][474][475] Châu appears before the camera several times, talking about his experiences and the situations during the conflict, in the 2017 PBS 10-part documentary series The Vietnam War produced by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

The difference was that many of the communists were Châu's friends, including his brothers and sisters, and however misguided he considered their ideology, he knew them as patriots – not as faceless members of a Moscow-directed conspiracy, as Washington saw them.

One innovation of the CIA was the Static Census Grievance program, which sent people into the villages to survey one member of each family in order to identify the villagers' grievances against the government and to gather intelligence.Moyar continues (at 37–38) with other "CIA initiatives" which follow pacification techniques similar or parallel to Châu's, e.g., the "Armed Propaganda Team", the "Province Interrogation Center", and the highly touted "Revolutionary Development (RD) cadres program, which imitated the Viet Cong" as well as "Counter-Terror Teams".

Once the villagers were convinced that the process produced results, the teams proceeded to [ask] about local Communist activities and identities to help the province's intelligence service to combat the Viet Cong infrastructure.

or the Viet Cong

according to David Kilcullen (2006)