Mahatma Gandhi

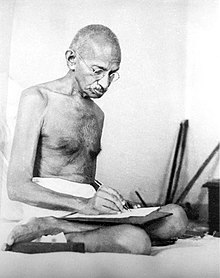

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[c] (2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948)[2] was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule.

After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, Gandhi moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit.

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule.

Among these was Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist from Pune, western India, who assassinated Gandhi by firing three bullets into his chest at an interfaith prayer meeting in Delhi on 30 January 1948.

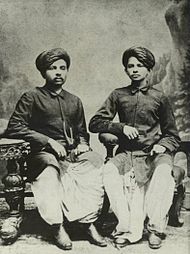

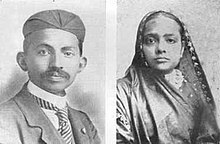

[27] In May 1883, the 13-year-old Gandhi was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Gokuldas Kapadia (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged marriage, according to the custom of the region at that time.

[30] Writing many years later, Gandhi described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride: "Even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me."

[43] Upon arrival in Bombay, he stayed with the local Modh Bania community whose elders warned Gandhi that England would tempt him to compromise his religion, and eat and drink in Western ways.

Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, Gandhi joined the London Vegetarian Society (LVS) and was elected to its executive committee under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills.

He returned to Rajkot to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, but Gandhi was forced to stop after running afoul of British officer Sam Sunny.

According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi wanted to disprove the British colonial stereotype that Hindus were not fit for "manly" activities involving danger and exertion, unlike the Muslim "martial races.

At the Battle of Spion Kop, Gandhi and his bearers moved to the front line and had to carry wounded soldiers for miles to a field hospital since the terrain was too rough for the ambulances.

[77] In 1906, when the Bambatha Rebellion broke out in the colony of Natal, the then 36-year-old Gandhi, despite sympathising with the Zulu rebels, encouraged Indian South Africans to form a volunteer stretcher-bearer unit.

"[88] According to political and educational scientist Christian Bartolf, Gandhi's support for the war stemmed from his belief that true ahimsa could not exist simultaneously with cowardice.

The Act allowed the British government to treat civil disobedience participants as criminals and gave it the legal basis to arrest anyone for "preventive indefinite detention, incarceration without judicial review or any need for a trial.

[5][116] In February 1919, Gandhi cautioned the Viceroy of India with a cable communication that if the British were to pass the Rowlatt Act, he would appeal to Indians to start civil disobedience.

[117] On 13 April 1919, people including women with children gathered in an Amritsar park, and British Indian Army officer Reginald Dyer surrounded them and ordered troops under his command to fire on them.

He pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country as its goal.

British political leaders such as Lord Birkenhead and Winston Churchill announced opposition to "the appeasers of Gandhi" in their discussions with European diplomats who sympathised with Indian demands.

Gandhi condemned British rule in the letter, describing it as "a curse" that "has impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation and by a ruinously expensive military and civil administration...

A horrified American journalist, Webb Miller, described the British response thus: In complete silence the Gandhi men drew up and halted a hundred yards from the stockade.

The plays built support among peasants steeped in traditional Hindu culture, according to Murali, and this effort made Gandhi a folk hero in Telugu speaking villages, a sacred messiah-like figure.

[138] In Britain, Winston Churchill, a prominent Conservative politician who was then out of office but later became its prime minister, became a vigorous and articulate critic of Gandhi and opponent of his long-term plans.

Churchill called him a dictator, a "Hindu Mussolini", fomenting a race war, trying to replace the Raj with Brahmin cronies, playing on the ignorance of Indian masses, all for selfish gain.

[141] Gandhi vehemently opposed a constitution that enshrined rights or representations based on communal divisions, because he feared that it would not bring people together but divide them, perpetuate their status, and divert the attention from India's struggle to end the colonial rule.

[178] Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy and Governor-General of British India for three years through February 1947, had worked with Gandhi and Jinnah to find a common ground, before and after accepting Indian independence in principle.

It was the satyagraha formulation and step, states Dennis Dalton, that deeply resonated with beliefs and culture of his people, embedded him into the popular consciousness, transforming him quickly into Mahatma.

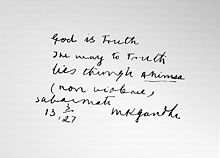

[237] Gandhi, states Richards, described the term "God" not as a separate power, but as the Being (Brahman, Atman) of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, a nondual universal that pervades in all things, in each person and all life.

[248][249][250] The untouchability leader Ambedkar, in June 1945, after his decision to convert to Buddhism and the first Law and Justice minister of modern India, dismissed Gandhi's ideas as loved by "blind Hindu devotees", primitive, influenced by spurious brew of Tolstoy and Ruskin, and "there is always some simpleton to preach them".

"[320] Time magazine named The 14th Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to nonviolence.

His vision of a village-dominated economy was shunted aside during his lifetime as rural romanticism, and his call for a national ethos of personal austerity and nonviolence has proved antithetical to the goals of an aspiring economic and military power."