Transcendentalism

Emphasizing subjective intuition over objective empiricism, its adherents believe that individuals are capable of generating completely original insights with little attention and deference to past transcendentalists.

It started to develop after Unitarianism took hold at Harvard University, following the elections of Henry Ware as the Hollis Professor of Divinity in 1805 and of John Thornton Kirkland as President in 1810.

Other members of the club included Sophia Ripley, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Peabody, Ellen Sturgis Hooper, Caroline Sturgis Tappan, Amos Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, Theodore Parker, Henry David Thoreau, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, Convers Francis, Sylvester Judd, Jones Very, and Charles Stearns Wheeler.

"[10] There was, however, a second wave of transcendentalists later in the 19th century, including Moncure Conway, Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Samuel Longfellow and Franklin Benjamin Sanborn.

[12] The group was mostly made up of struggling aesthetes, the wealthiest among them being Samuel Gray Ward, who, after a few contributions to The Dial, focused on his banking career.

Transcendentalists desire to ground their religion and philosophy in principles based upon the German Romanticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Schleiermacher.

Early transcendentalists were largely unacquainted with German philosophy in the original and relied primarily on the writings of Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Victor Cousin, Germaine de Staël, and other English and French commentators for their knowledge of it.

While firmly rooted in the western philosophical traditions of Platonism, Neoplatonism, and German idealism, Transcendentalism was also directly influenced by Indian religions.

[17][18][note 1] Thoreau in Walden spoke of the Transcendentalists' debt to Indian religions directly: In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water-jug.

In his 1842 lecture "The Transcendentalist", he suggested that the goal of a purely transcendental outlook on life was impossible to attain in practice: You will see by this sketch that there is no such thing as a transcendental party; that there is no pure transcendentalist; that we know of no one but prophets and heralds of such a philosophy; that all who by strong bias of nature have leaned to the spiritual side in doctrine, have stopped short of their goal.

Standing on the bare ground, – my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, – all mean egotism vanishes.

[25] As early as 1843, in Summer on the Lakes, Margaret Fuller noted that "the noble trees are gone already from this island to feed this caldron",[26] and in 1854, in Walden, Thoreau regarded the trains being built across America's landscape as a "winged horse or fiery dragon" that "sprinkle[d] all the restless men and floating merchandise in the country for seed".

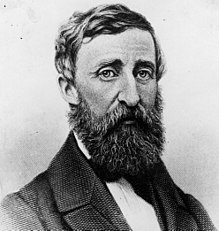

[37][38][39] Major figures in the transcendentalist movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott.

Some other prominent transcendentalists included Louisa May Alcott, Charles Timothy Brooks, Orestes Brownson, William Ellery Channing, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, John Sullivan Dwight, Convers Francis, William Henry Furness, Frederic Henry Hedge, Sylvester Judd, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, George Ripley, Thomas Treadwell Stone, Jones Very, and Walt Whitman.

[41] Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a novel, The Blithedale Romance (1852), satirizing the movement, and based it on his experiences at Brook Farm, a short-lived utopian community founded on transcendental principles.

[42] In Edgar Allan Poe's satires "How to Write a Blackwood Article" (1838) and "Never Bet the Devil Your Head" (1841), the author ridicules transcendentalism,[43] elsewhere calling its followers "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common.