Transfer pricing

[1][2] The OECD and World Bank recommend intragroup pricing rules based on the arm’s-length principle, and 19 of the 20 members of the G20 have adopted similar measures through bilateral treaties and domestic legislation, regulations, or administrative practice.

[9] These adjustments are generally calculated using one or more of the transfer pricing methods specified in the OECD guidelines[10] and are subject to judicial review or other dispute resolution mechanisms.

[17] However, aggressive intragroup pricing – especially for debt and intangibles – has played a major role in corporate tax avoidance,[18] and it was one of the issues identified when the OECD released its base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) action plan in 2013.

[21] These recommendations have been criticized by many taxpayers and professional service firms for departing from established principles[22] and by some academics and advocacy groups for failing to make adequate changes.

[25] Over sixty governments have adopted transfer pricing rules,[26] which in almost all cases (with the notable exception of Kazakhstan) are based on the arm's-length principle.

Many systems differentiate methods of testing goods from those for services or use of property due to inherent differences in business aspects of such broad types of transactions.

The United States led the development of detailed, comprehensive transfer pricing guidelines with a White Paper in 1988 and proposals in 1990–1992, which ultimately became regulations in 1994.

The U.S. and OECD rules require that reliable adjustments must be made for all differences (if any) between related party items and purported comparables that could materially affect the condition being examined.

Terms that may impact price include payment timing, warranty, volume discounts, duration of rights to use of the product, form of consideration, etc.

For example, a head of cauliflower at a retail market will command a vastly different price in unelectrified rural India than in Tokyo.

Buyers or sellers may have different market shares that allow them to achieve volume discounts or exert sufficient pressure on the other party to lower prices.

To combat this, the rules of most systems allow the tax authorities to challenge whether the services allegedly performed actually benefit the member charged.

[68] OECD Guidelines provide more generalized suggestions to tax authorities for enforcement related to cost contribution agreements (CCAs) with respect to acquisition of various types of assets.

[70] A key requirement to limit adjustments related to costs of developing intangible assets is that there must be a written agreement in place among the members.

[71] Tax rules may impose additional contractual, documentation, accounting, and reporting requirements on participants of a CSA or CCA, which vary by country.

U.S. rules specifically provide that a taxpayer's intent to avoid or evade tax is not a prerequisite to adjustment by the Internal Revenue Service, nor are nonrecognition provisions.

The Comparable Profits method (CPM)[80] was introduced in the 1992 proposed regulations and has been a prominent feature of IRS transfer pricing practice since.

Prices charged are considered arm's length where the costs are allocated in a consistent manner among the members based on reasonably anticipated benefits.

For instance, shared services costs may be allocated among members based on a formula involving expected or actual sales or a combination of factors.

[94] OECD rules generally do not permit tax authorities to make adjustments if prices charged between related parties are within the arm's length range.

Taxpayers affected by the rules who engaged in intercompany transactions under RMB 20 million for the year were generally exempted from reporting, documentation, and penalties.

Those with transactions exceeding RMB 200 million generally were required to complete transfer pricing studies in advance of filing tax returns.

The draft also requires companies involved with related-party service transactions, cost sharing agreements or thin capitalization to submit a so-called "Special File.

The guidelines for CUP include specific functions and risks to be analyzed for each type of transaction (goods, rentals, licensing, financing, and services).

Tax authorities of most major countries have entered into unilateral or multilateral agreements between taxpayers and other governments regarding the setting or testing of related party prices.

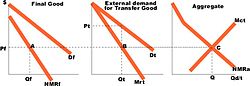

A frequently-proposed[107][108] alternative to arm's-length principle-based transfer pricing rules is formulary apportionment, under which corporate profits are allocated according to objective metrics of activity such as sales, employees, or fixed assets.

[109][110] According to the amicus curiae brief, filed by the attorneys general of Alaska, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon in support of the state of California in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Barclays Bank PLC v. Franchise Tax Board, the formulary apportionment method, which is also known as the unitary apportionment method, has at least three major advantages over the separate accounting system when applied to multi-jurisdictional businesses.

First, the unitary method captures the added wealth and value resulting from economic interdependencies of multistate and multinational corporations through their functional integration, centralization of management, and economies of scale.

By attempting to treat those businesses which are in fact unitary as independent entities, separate accounting "operates in a universe of pretense; as in Alice in Wonderland, it turns reality into fancy and then pretends it is the real world".

However, since the participating countries are sovereign entities, obtaining data and initiating meaningful actions to limit tax avoidance is hard.